Great white sharks can live almost as long as humans — 70 years or more — much longer than scientists previously thought.

"White sharks in the northwest Atlantic are considerably older than previous age estimates," some of which pegged the oldest great white sharks at around 23 years old, said study co-author Li Ling Hamady, an oceanography graduate student at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts.

The findings, detailed today (Jan. 8) in the journal PLOS ONE, suggest that the apex predators may take longer to reach maturity than previously thought and, therefore, may be more vulnerable to overfishing. [Image Gallery: Great White Sharks]

Shark tree rings

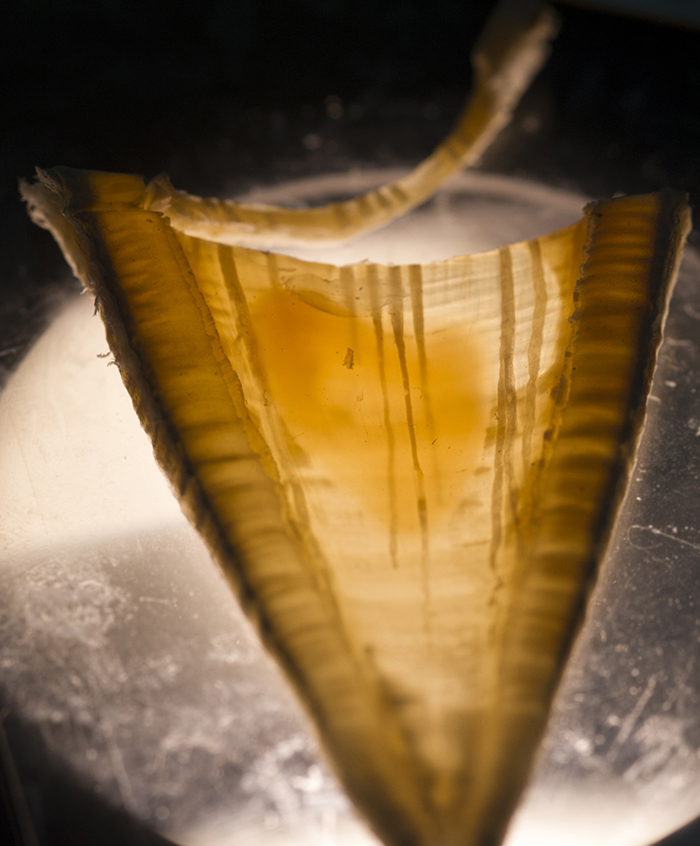

Figuring out a great white shark's age is tricky. Researchers typically look at shark teeth, ear bones, vertebrae and bony rods in the skeleton to make age estimations. Because these body parts grow throughout a shark's life, they retain layers of tissue that are laid out in light and dark stripes, similar to tree rings.

Previously, researchers assumed that each stripe corresponded to annual growth, which isn't necessarily true throughout a shark's life. And because these bands can vary in width and coloration, it can be difficult to distinguish them.

Instead, Hamady and her colleagues took advantage of the fact that nuclear bomb testing from the mid-1950s to the 1960s produced huge amounts of carbon-14, a radioactive isotope, or variant of carbon with more neutrons than the dominant form. That carbon-14 fell from the atmosphere into the ocean and was taken up by marine animals at the time, so tissue from that time period shows a distinctive rise in the levels of carbon-14 compared with the background levels found in the environment.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team analyzed the radiocarbon from the vertebrae of four female and four male great white sharks that were captured in the Atlantic Ocean from 1967 to 2010.

The nuclear testing"provides a time stamp for us to determine when these tissue layers were deposited," Hamady told LiveScience.

By counting the rings before and after that spike, the authors could deduce the age of the sharks. The team found the sharks' "tree ring" bands were laid down in annual stripes for small to medium-size sharks. After that, however, there was a change in how often these stripes appeared, and the bands became so thin that they were difficult to distinguish.

Longer lives

Amazingly, the biggest male shark was 73 years old, and the largest female shark was 40 years old, the researchers determined. (Right now, the researchers don't have enough data to say whether the females have a different life span than the males.)

The findings suggest that sharks may have a life course similar to that of humans. If that's the case, then the ocean predators may mature slowly, as humans do. So, the sharks, which are listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as vulnerable, would take longer to reproduce and raise population numbers in the case of overfishing, Hamady said.

The longer lives of great white sharks are consistent with increased life spans being found using the same method in sandbar and tiger sharks, said Allen Andrews, a biologist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries - Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center in Honolulu, who was not involved in the work.

"There's basically missing time in the vertebrae of these sharks," Andrews told LiveScience. "We're finding the vertebrae just stop growing, and very likely if there is growth there, it's too small to see, or maybe it's lost in the cleaning process," he said, referring to the process of cleaning the vertebrae prior to analysis.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus