What is normal blood pressure?

Here's what doctors consider a "normal," elevated or high blood pressure, and how to measure your BP at home.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Blood pressure is one of the vital signs that doctors measure to assess their patients' general health.

When the heart pumps blood through the arteries — the tubes that carry oxygenated blood away from the heart — the blood puts pressure on the artery walls. Having blood pressure measures consistently above normal may result in a diagnosis of high blood pressure, or hypertension. High blood pressure increases the risk for heart disease, heart attack and stroke, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

But what is considered to be “normal” blood pressure, and how is blood pressure measured?

What is normal blood pressure?

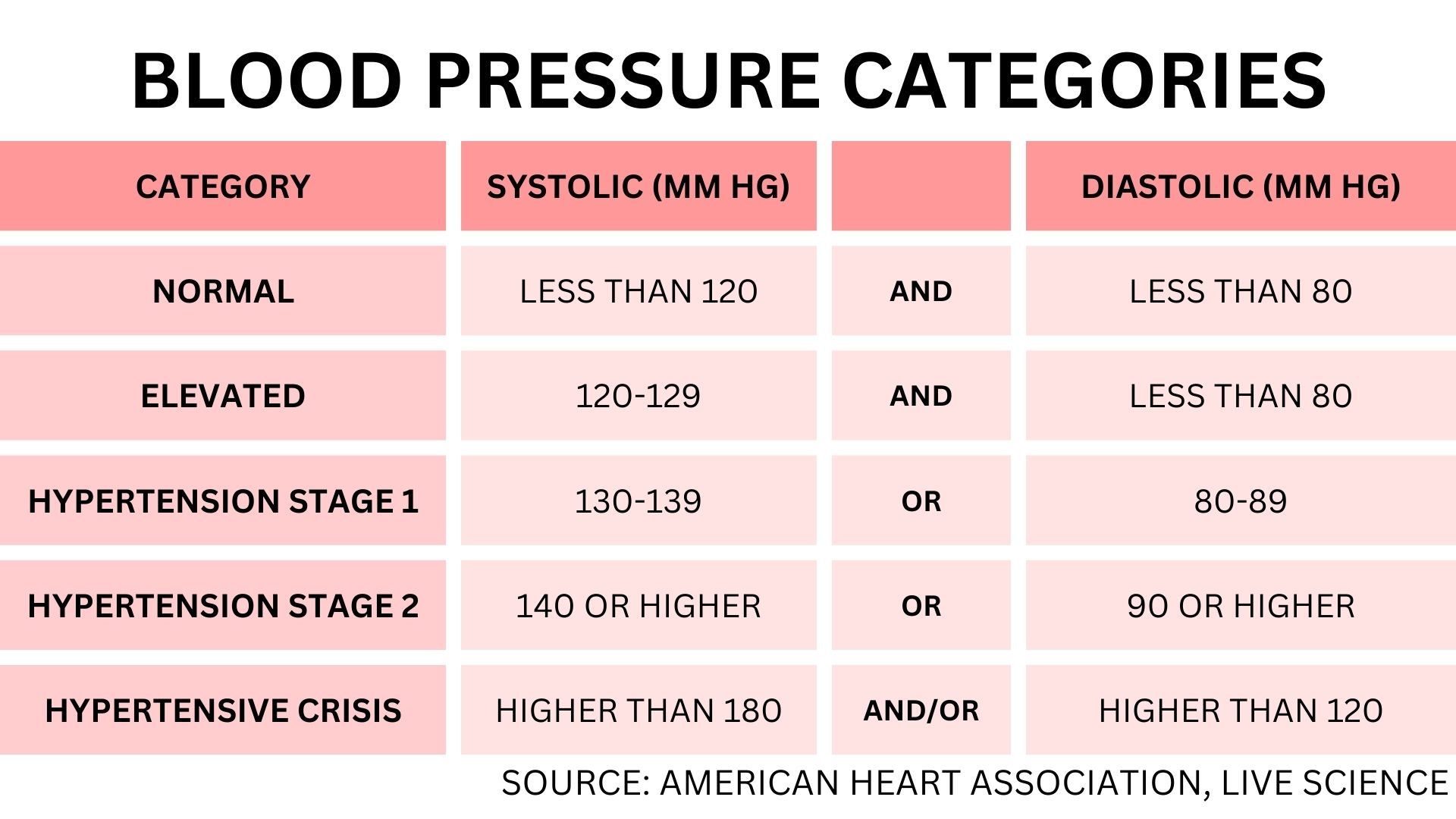

According to the CDC, blood pressure is measured in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg) and written as a ratio of two numbers. The first number, called systolic blood pressure, measures the pressure within the arteries when the heart beats. The second number, called diastolic blood pressure, measures the pressure within the arteries when the heart rests between beats.

Normal blood pressure is defined as less than 120/80 mm Hg, meaning a person's systolic blood pressure measures below 120 mm Hg and their diastolic runs below 80 mm Hg, according to the American Heart Association (AHA). High blood pressure, also called hypertension, is defined as 130/80 mm Hg or higher.

Here's a summary of how each blood pressure category is defined, according to the ADA's 2017 guidelines:

- Normal: Less than 120 mm Hg for systolic and 80 mm Hg for diastolic.

- Elevated: Between 120-129 mm Hg for systolic, and less than 80 mm Hg for diastolic.

- Stage 1 hypertension: Between 130 and 139 mm Hg for systolic or between 80 and 89 mm Hg for diastolic.

- Stage 2 hypertension: At least 140 mm Hg for systolic or at least 90 mm Hg for diastolic.

Low blood pressure, known as hypotension, is typically defined as being lower than 90/60 mm Hg. Although some people's blood pressure stays relatively low all the time, others experience sudden dips in their blood pressure that can be dangerous, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What causes blood pressure to rise?

A number of lifestyle and environmental factors will determine a person's blood pressure, Dr. Mary Ann Bauman, a specialist in internal medicine at Integris Baptist Medical Center in Oklahoma City, told Live Science. Some of these factors, such as age, cannot be controlled.

"People are born with very elastic vessels that can expand easily, and bounce back when the pressure on them is low. As people age, they get plaque buildup inside the blood vessels, and the flexible walls of the arteries become stiff," she said. "Now, when the heart squeezes and pushes the blood out, the blood vessels can't expand like they used to and sustain higher pressure. Over time, the heart has to push so hard against the pressure that it starts to fail."

Physical activity is crucial to the maintenance of normal blood pressure, Bauman said. Professional athletes and people who regularly exercise tend to have lower risk of developing hypertension than those who do not engage in sufficient physical activity, according to a 2017 meta-analysis published in the journal Hypertension. In particular, endurance exercises, such as walking and running, have been shown to help lower blood pressure.

In addition to inactivity, factors that can raise blood pressure include stress, smoking, caffeine, consuming too much salt, binge drinking and certain medications.

High blood pressure can cause a number of health issues, including the hardening of the arteries — or atherosclerosis — kidney disease and heart disease. High blood pressure can also result in stroke, caused by either a blocked or ruptured artery, according to the CDC.

How to check your blood pressure

The AHA recommends that, starting at age 20, adults have their blood pressure checked at their regular healthcare visit or once every two years, if their blood pressure is less than 120/80 mm Hg.

People who have high blood pressure are encouraged to check their blood pressure at least three times a week, Bauman said.

People can check their blood pressure themselves. Monitoring blood pressure at home sometimes may be better than doing so at the doctor's office, Bauman said, partly because people are especially susceptible to a stress-related spike in their blood pressure when they visit a doctor — a situation known as "white coat hypertension."

Related: Best fitness trackers 2023

"We have many studies that indicate people taking their blood pressure at home is much more accurate than at the doctor's office," Bauman said.

A manual or digital blood pressure monitor (sphygmomanometer) typically comes with instructions that should be followed carefully to get the most accurate results.

Usually when using a blood pressure monitor, the user first needs to find their pulse by pressing an index finger on the brachial artery, which is at the bend of the elbow, slightly to the inside center. On a manual monitor, the user then places the head of the stethoscope in the general area of this artery and under the inflatable blood pressure cuff. For a digital monitor, the cuff is placed in this area.

For a manual blood pressure monitor, the user holds the pressure gauge in their nondominant hand and the bulb in the other hand and inflates the cuff until it reads about 30 points above their usual systolic pressure. At this point, the pulse shouldn’t be audible in the stethoscope. When the first heart beat can be heard, this is the systolic pressure. As the cuff deflates, keep listening for a heart beat — when it can no longer be heard, that is the diastolic pressure.

Digital monitors handle the inflation and deflation of the cuff automatically, as well as the recording of the systolic and diastolic blood pressure.

How do you treat high blood pressure?

Treating high blood pressure involves lifestyle changes and prescription medication for those with readings of 140/90 mm Hg or higher, according to the AHA.

"The first thing we tell people to do if their blood pressure is in prehypertension range, is to lose weight, exercise more, and reduce salt in diet," Bauman said. "If they reach higher levels, we then treat them with medications."

These medications include:

- Diuretics: Diuretics help the body get rid of excess sodium (salt) and water and help control blood pressure.

- Beta-blockers: Beta-blockers reduce the heart rate, the heart's workload and the heart's output of blood, which lowers blood pressure.

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors: ACE inhibitors lower the body’s production of angiotensin, a chemical that causes the arteries to become narrow. These medications help the blood vessels relax and open up, which, in turn, lowers blood pressure.

- Calcium channel blockers: Calcium channel blockers relax and open up narrowed blood vessels, reduce heart rate and lower blood pressure.

"Having a healthy lifestyle really makes a difference in your life because you can avoid high blood pressure," Bauman said. "If you do have high blood pressure, make sure to take your medication. You may not necessarily have symptoms until your blood pressure gets really high."

Anna Gora is a health writer at Live Science, having previously worked across Coach, Fit&Well, T3, TechRadar and Tom's Guide. She is a certified personal trainer, nutritionist and health coach with nearly 10 years of professional experience. Anna holds a Bachelor's degree in Nutrition from the Warsaw University of Life Sciences, a Master’s degree in Nutrition, Physical Activity & Public Health from the University of Bristol, as well as various health coaching certificates. She is passionate about empowering people to live a healthy lifestyle and promoting the benefits of a plant-based diet.

- Kim Ann ZimmermannLive Science Contributor

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus