Australia's Oldest Bird Footprints Discovered

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

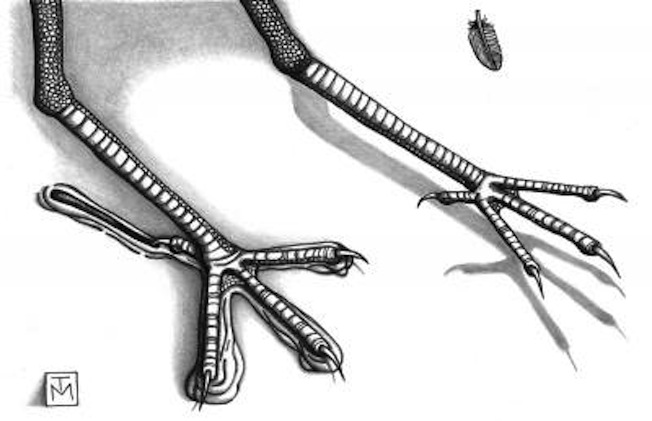

Two thin-toed footprints pressed into a sandy riverbank more than 100 million years ago are Australia's oldest known bird tracks, researchers say.

The prints were found among the fossil-rich cliffs of Dinosaur Cove on the coast of southern Victoria. Researchers think the tracks were left by a prehistoric bird species likely the size of a great egret or a small heron during the Early Cretaceous Period.

At that time, the world was warmer and the continents were arranged in different positions than they are today. The site of Dinosaur Cove was located in a floodplain in a great rift valley that formed as the supercontinent Gondwana started breaking apart, tearing Australia away from Antarctica. [Avian Ancestors: Dinosaurs That Learned to Fly]

A long drag mark leading up to one of the fossilized footprints was a telltale sign that these tracks were left by flying creatures, explained study researcher Anthony Martin, a paleontologist at Emory University in Atlanta.

The bird tracks were found very close to another footprint that looks like it was left by a non-avian theropod, possibly one of the coelurosaurs, the group of dinosaurs most closely related to birds that includes beasts like the Tyrannosaurus rex.

All three ancient footprints were locked in sandstone in an area smaller than a square foot (650 square centimeters), which gives researchers insight into the types of creatures that lived together at Dinosaur Cove during the Early Cretaceous.

"These tracks are evidence that we had sizeable, flying birds living alongside other kinds of dinosaurs on these polar, river floodplains, about 105 million years ago," Martin said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers think the footprints were left at a time when the riverbank was covered in moist sand, possibly after spring and summer floodwaters had subsided. Martin said it remains unclear whether these ancient birds lived in the region during the polar winter or migrated there during the spring and summer.

The birds that left their tracks at Dinosaur Cove also had one backwards-facing toe. That feature is found on some bird feet today, and T. rex even had a vestigial rear toe. Studying the changing toe-arrangement of birds and their dinosaur cousins could give researchers insight into the evolution of these species.

"In some dinosaur lineages, that rear toe got longer instead of shorter and made a great adaptation for perching up in trees," Martin explained in a statement. "Tracks and other trace fossils offer clues to how non-avian dinosaurs and birds evolved and started occupying different ecological niches."

The finding was described this month in the journal Palaeontology.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus