Seafloor Scours Hint at Ancient Arctic Ice Sheet

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

When deep ice sheets chilled most of North America and Europe 20,000 years ago, Alaska and eastern Siberia remained remarkably ice-free, providing passage for America's first humans.

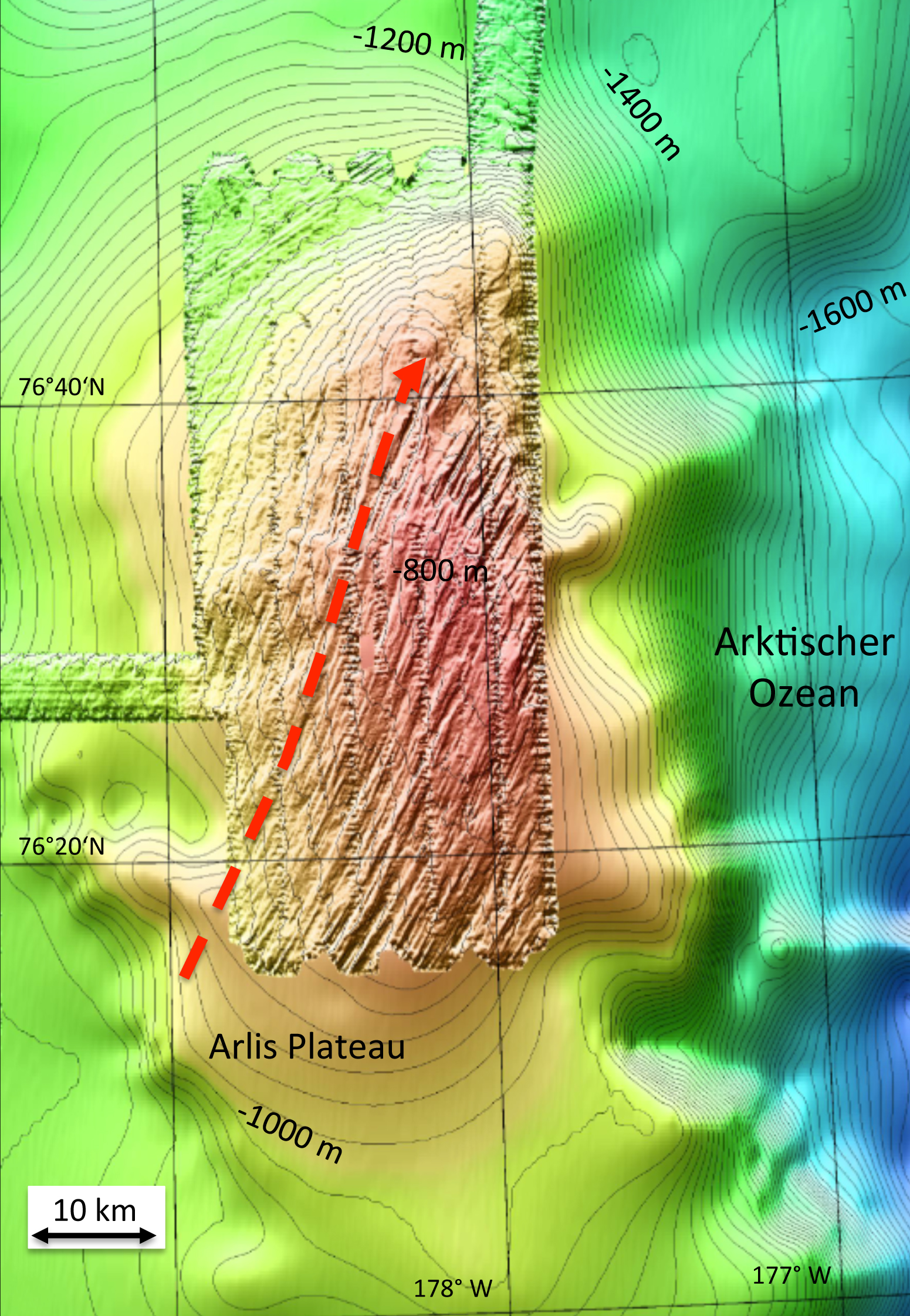

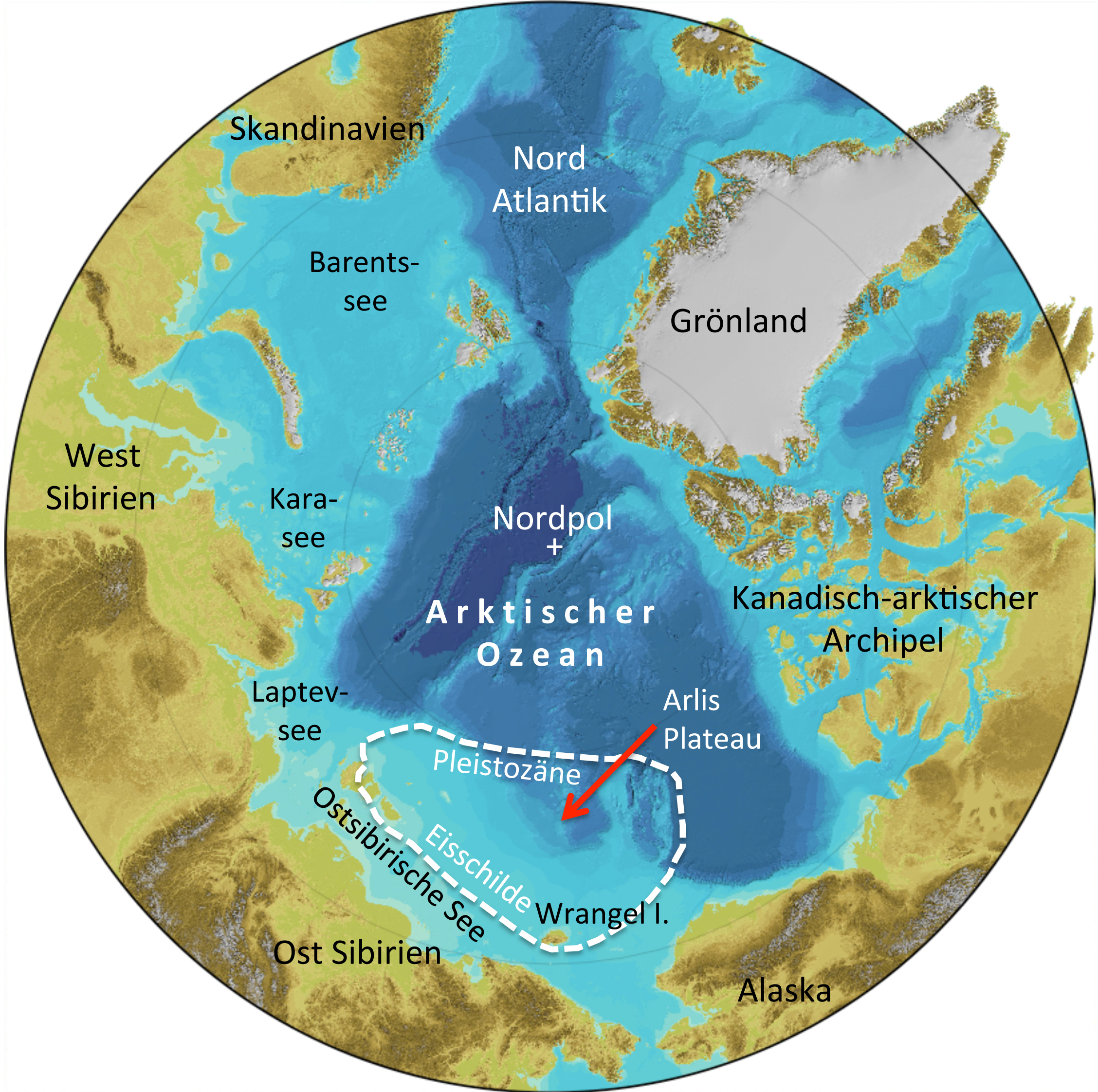

But before the explorers arrived, during earlier Pleistocene ice ages, an ice sheet more than half a mile (about 1 kilometer) thick jutted into the Arctic Ocean from Siberia, a new study finds. Seafloor surveys near Wrangel Island (off the coast of Siberia) and the Arlis Plateau revealed deep scratches carved by glaciers and preserved in the seafloor. There is more than one set of glacial grooves, and the researchers think at least four ice sheets existed, going back as far as 800,000 years.

"We knew of such scour marks from places like the Antarctic and Greenland," geologist Frank Niessen of the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany said in a statement.

"They arise when large ice sheets become grounded on the ocean floor and then scrape over the ground like a plane with dozens of blades as they flow. The remarkable feature of our new map is that it indicates very accurately right off that there were four or more generations of ice masses, which in the past 800,000 years moved from the East Siberian Sea in a northeasterly direction far into the deep Arctic Ocean," said Niessen, the lead study author.

The ancient traces cover an area the size of Scandinavia. The discovery is unique in the Arctic because the continental ice sheets in Greenland, Europe and North America never extended offshore, the researchers said. [Photos of Melt: Glaciers Before and After]

"Previously, many scientists were convinced that mega-glaciations always took place on the continents — a fact that has also been proven for Greenland, North America and Scandinavia," Niessen said in the statement.

Though the scratches and glacial deposits preserved in the seafloor suggest there were four glaciations in this region of the Arctic, the researchers haven't yet matched the sediments with global coolings recorded in ice cores or ocean records. But they can confirm that there was no big ice patch about 20,000 years ago, when scientists think the Bering Land Bridge, or Beringia, provided a refuge for animals during the great chill.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"With the exception of the last ice age 21,000 years ago, ice sheets formed repeatedly in the shallow areas of the Arctic Ocean," Niessen said. "Our long-term goal is to reconstruct the exact chronology of the glaciations so that with the aid of the known temperature and ice data, the ice sheets can be modeled," Niessen said. "On the basis of the models, we then hope to learn what climate conditions prevailed in Eastern Siberia during the ice ages and how, for example, the moisture distribution in the region evolved during the ice ages."

The findings were published Aug. 11 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus