Fracking Practices to Blame for Ohio Earthquakes

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Wastewater from the controversial practice of fracking appears to be linked to all the earthquakes in a town in Ohio that had no known past quakes, research now reveals.

The practice of hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, involves injecting water, sand and other materials under high pressures into a well to fracture rock. This opens up fissures that help oil and natural gas flow out more freely. This process generates wastewater that is often pumped underground as well, in order to get rid of it.

A furious debate has erupted over the safety of the practice. Advocates claim fracking is a safe, economical source of clean energy, while critics argue that it can taint drinking water supplies, among other problems.

One of the most profitable areas for fracking lies over the geological formation known as the Marcellus Shale, which reaches deep underground from Ohio and West Virginia northeast into Pennsylvania and southern New York. The Marcellus Shale is rich in natural gas; geologists estimate it may contain up to 489 trillion cubic feet (13.8 trillion cubic meters) of natural gas, more than 440 times the amount New York State uses annually. Many of the rural communities living over the formation face economic challenges and want to attract money from the energy industry.

Youngstown quakes

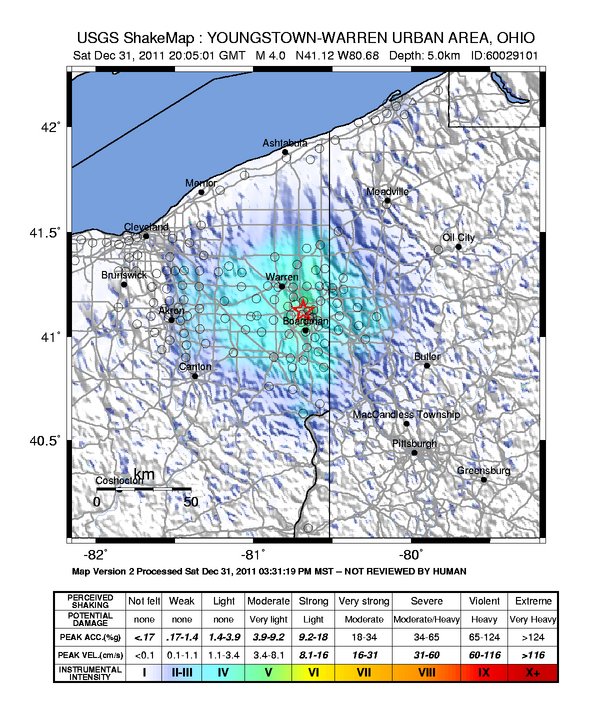

Before January 2011, Youngstown, Ohio, which is located on the Marcellus Shale, had never experienced an earthquake, at least not since researchers began observations in 1776. However, in December 2010, the Northstar 1 injection well came online to pump wastewater from fracking projects in Pennsylvania into storage deep underground. In the year that followed, seismometers in and around Youngstown recorded 109 earthquakes, the strongest registering a magnitude-3.9 earthquake on Dec. 31, 2011. The well was shut down after the quake.

Scientists have known for decades that fracking and wastewater injection can trigger earthquakes. For instance, it appears linked with Oklahoma's strongest recorded quake in 2011, as well as a rash of more than 180 minor tremors in Texas between Oct. 30, 2008, and May 31, 2009.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new investigation of the Youngstown earthquakes, detailed in the July issue of the journal Geophysical Research Letters, reveals that their onset, end and even temporary dips in activity were apparently all tied to activity at the Northstar 1 well.

For instance, the first earthquake recorded in Youngstown occurred 13 days after pumping began, and the tremors ceased shortly after the Ohio Department of Natural Resources shut down the well in December 2011. In addition, dips in earthquake activity lined up with Memorial Day, the Fourth of July, Labor Day, Thanksgiving and other times when injection at the well was temporarily stopped.

"Earthquakes were triggered by fluid injection shortly after the injection initiated — less than two weeks," researcher Won-Young Kim, a seismologist at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in Palisades, N.Y., told LiveScience. "Previously, we knew [of] unusual earthquakes around Youngstown, Ohio, only on March 17, around 80 days after injection began. If we had better seismographic station coverage, or if we were more careful, we could have caught those early events."

Ancient fault

The earthquakes were apparently centered in an ancient fault near the Northstar 1 well, and Kim suggested pressure from wastewater injection caused this fault to rupture. The quakes crept from east to west down the length of the fault — away from the well — throughout the year, a sign that they were caused by a traveling front of pressure generated by the injected fluid.

The researchers did note that of the 177 wastewater disposal wells of this size active in Ohio during 2011, only the Northstar 1 well was linked with this kind of seismic activity, suggesting this ability to cause earthquakes was rare. Kim personally felt injecting wastewater deep underground "is a fairly good method of massive fluid waste disposal."

Kim stressed these earthquakes are not directly related to fracking of rock for natural gas. "They are due to injection of waste fluid from fracking," he noted.

In the future, "we need to find better ways to image hidden subsurface faults and fractures, which is costly at the moment," Kim said. "If there are hidden subsurface faults near the injection wells, then sooner or later they can trigger earthquakes."

In the future, operators of such wells may look for earthquakes for about six months after the beginning of operations, Kim said.

"However, there are cases when triggered earthquakes occurred nearly 10 years after the injection," he noted.

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus