New Antarctic Iceberg Staying Put

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

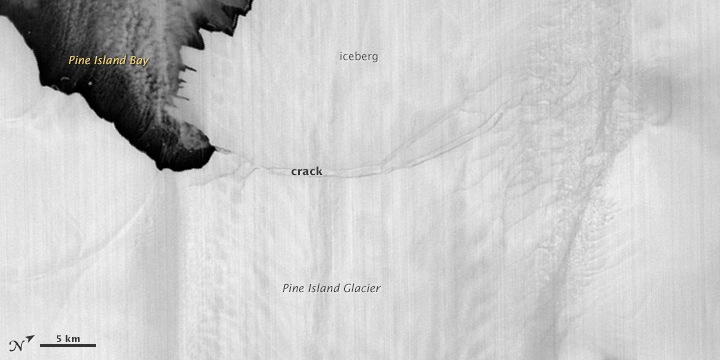

The huge iceberg that broke off of Antarctica's Pine Island Glacier (PIG) on July 8 hasn't budged from the coastline of the southernmost continent, to move out into Pine Island Bay and the Amundsen Sea, a new false-color satellite image of the glacier and its iceberg show.

The image, featured on NASA's Earth Observatory, shows that the 280-square-mile (720-square-kilometer) iceberg hasn't moved much since it first formed. The new image was taken by the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) instrument on NASA's Terra satellite on July 14. How long it will take the iceberg to move out to sea is unclear, the Earth Observatory reports, noting that rock and ice could be creating friction that is impeding the iceberg's movement. Winds and currents could also be pressing the iceberg against the coast, as could sea ice, emeritus NASA scientist Robert Bindschadler, who has studied PIG for more than a decade, told the Earth Observatory.

Bindschadler is part of a team that has been visiting PIG to place GPS receivers and other instruments to monitor the flow of the glacier, which is one of the largest and fastest moving in Antarctica. He told the Earth Observatory that the team will be looking to see if the calving (or breaking off) of the iceberg impacted the flow of the glacier.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus