Inbreeding: Downfall of a Dynasty

The powerful Habsburg dynasty that ruled Spain for nearly 200 years came to an abrupt end in 1700 with the death of King Charles II, who left no heirs to the throne.

The termination of that royal lineage may be the result of frequent inbreeding of the line, which may have left Charles II ill and infertile, a new study suggests.

The House of Habsburg was one of the major royal houses of Europe for many centuries. The Habsburgs ruled over Austria for more than six centuries, eventually coming to rule (through marriages) over Bohemia, Hungary and Spain.

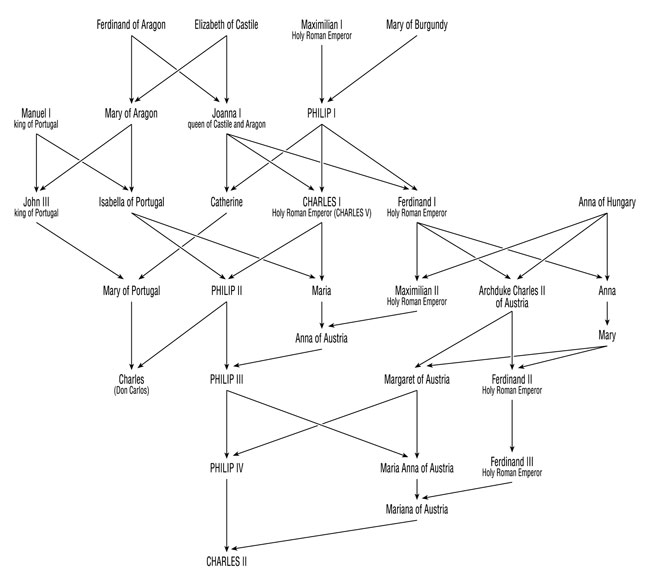

The Spanish Habsburg dynasty was founded by Philip I (or Philip the Fair, son of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I) in 1516 when he married Joanna the Mad, the daughter of the Catholic Spanish rulers Ferdinand of Aragon and Elizabeth of Castile. The house ruled over Spain throughout the height of its influence and empire.

But, historical data show that "in order to keep their heritage in their own hands, the Spanish Habsburgs began to intermarry more and more frequently among themselves," the authors of the new study wrote.

Records show that the Spanish Habsburg kings frequently engaged in consanguineous marriage (or marriage between biological relatives); nine of the 11 marriages that occurred over the dynasty's 200-year reign were consanguineous, with two uncle-niece marriages and one first-cousin marriage.

It had been suggested that this high degree of inbreeding led to the eventual extinction of the line when the "physically disabled, mentally retarded and disfigured" Charles II died after two childless marriages, the authors wrote. But this idea had not before been examined from a genetic perspective.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Gonzalo Alvarez and his colleagues at the University of Santiago de Compostela in Spain calculated what is called the inbreeding coefficient for each individual across 16 generations of the Habsburgs, using genealogical information for Charles II and 3,000 of his relatives and ancestors. The inbreeding coefficient indicates the likelihood that an individual would receive two identical genes at a given position on a chromosome because of the relatedness of their parents.

Inbreeding evidence

Alvarez's team found that the inbreeding coefficient increased considerably down through the generations, from 0.025 for Philip I to 0.254 for Charles II — almost as high as would be expected for the offspring of an incestuous marriage (parent-child or brother-sister).

Charles II, who was dubbed El Hechizado ("The Hexed"), was the produce of an uncle-niece marriage — Phillip IV with his niece Mariana of Austria. His grandfather Philip III was also born of an uncle-niece marriage — Philip II with his niece Anna of Austria.

The high degree of relatedness of these rulers' parents combined with the remote inbreeding in the lineage likely had a significant impact on the eventual extinction of the line.

Other evidence that backs up this conclusion is the stark rate of infant and child mortality in the Habsburg families. Only about 60 percent of infants survived to age 1, and only half of the children born to the dynasty survived to age 10, compared with about 80 percent survival of infants in Spanish villages at the time.

Charles II's disorders and illnesses are also evidence of the inbreeding of the line. According to contemporary writings, he was short and weak and suffered from intestinal problems and sporadic hematuria (the presence of red blood cells in the urine). He did not speak until age 4 and did not walk until age 8.

Such detrimental health effects are often seen in children of consanguineous marriage because they are more likely to inherit rare deleterious recessive versions of genes.

Based on the historical information they gathered and clinical genetic knowledge, Alvarez and his colleague determined that Charles II's ailments and impotence/infertility (complained about by his spouses) are the result of two genetic disorders — combined pituitary hormone deficiency and distal renal tubular acidosis (a condition that causes acid to build up in the body because the kidneys are not properly channeling it into the urine).

With the death of Charles II (at the age of 39) and the end of the Spanish Habsburg line, the House of Bourbon of France assumed the Spanish crown.

The study's findings are detailed on April 14 in the online journal Public Library of Science ONE.

- The 10 Worst Hereditary Conditions

- The Sex Quiz: Myths, Taboos, and Bizarre Facts

- Incest Not So Taboo in Nature

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.