The human heart: Facts about the body's hardest-working muscle

Discover interesting facts about the fist-size organ that powers the circulatory system.

What the heart is made of: Heart muscle tissue, also called cardiac muscle tissue

What makes the heart beat: Electrical signals

Average resting heart rate: 60 to 100 beats per minute (in adults)

The heart is the body's hardest-working muscle. Whether you're awake or asleep, or exercising or resting, your heart is always at work. It pumps blood through arteries to deliver oxygen to organs and tissues around the body, and through veins to return "used" blood back to the heart.

The heart is located near the center of the chest, between the lungs, and is tilted slightly to the left. This muscular organ has four sections, called "chambers," that are made of special tissue called cardiac muscle. Electrical signals control the heartbeat, speeding it up or slowing it down depending on the body's needs and whether you're stressed or relaxed.

The heart powers the circulatory system, which includes a network of tubes that move blood through the body; this, in turn, delivers oxygen, nutrients and disease-fighting cells to the organs and tissues.

5 fast facts about the heart

- The heart of an average adult beats more than 100,000 times per day.

- A woman's heart beats faster than a man's by about eight beats per minute, on average.

- The rhythm of your pulse is the stopping and starting of blood moving through your arteries.

- In just 60 seconds, the average adult heart pumps about 1.5 gallons (5.7 liters) of blood.

- X-rays of ancient Egyptian mummies show that people had heart disease more than 3,000 years ago.

Everything you need to know about the heart

What is the shape of the heart?

Heart symbols in cartoons and emoji do not look like an actual human heart. In reality, the heart is more spherical in shape, except it's narrower at the bottom than the top. That said, its shape can vary from person to person. Some people's hearts are shaped more like a ball, and others' are longer and narrower. Hearts can change shape over time, too, with age and certain types of heart disease make them rounder.

A newborn baby's heart is about the size of a walnut. An adult heart is about the size of a fist and weighs between 7 and 15 ounces (200 to 425 grams) — that's about as much as a standard can of soda.

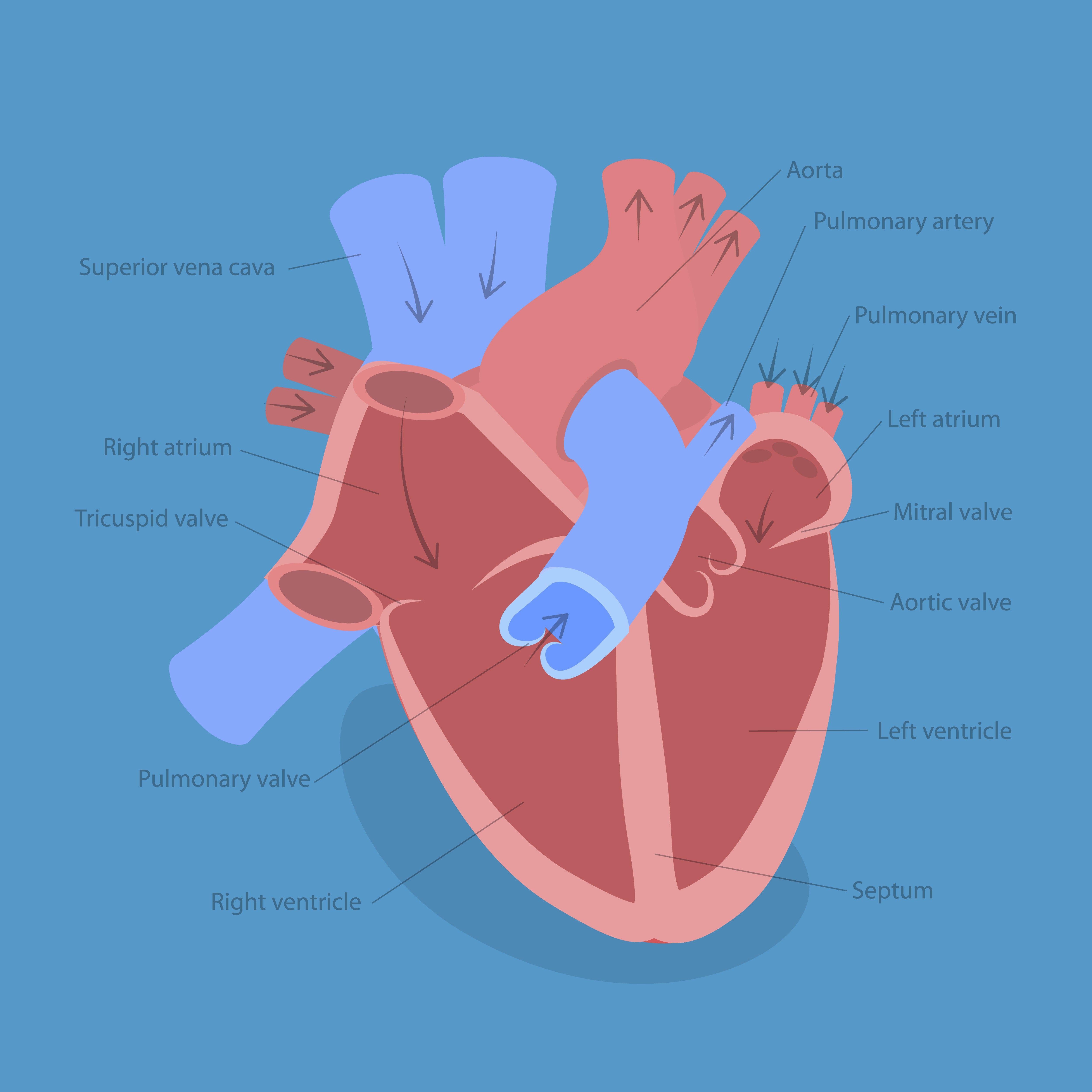

The heart has four sections, called chambers. The top two chambers are the atria, and the bottom two are the ventricles. A vertical wall of muscle separates the left and right sides of the heart. Attached to the heart are tubes called pulmonary blood vessels. "Pulmonary" means that they are related to the lungs, which supply blood with oxygen from the air you breathe. Pulmonary veins carry blood packed with oxygen to the heart, and pulmonary arteries transport blood that's sapped of oxygen away from it.

At the top left of the heart is the aorta — a pulmonary artery and the biggest blood vessel in the body. Its diameter in the adult body is about the same as that of a garden hose. The top of the aorta is curved, like a question mark. It carries oxygen-rich blood from the heart to the rest of the body. On the top right of the heart is another big blood vessel, the superior vena cava. This large vein brings blood that's low in oxygen- back to the heart, which then pumps the blood to the lungs so more oxygen can be added.

How does the heart beat?

There are two types of cells in the heart that control its beating. "Cardiac muscle cells" do the pumping work, and "conducting cells" carry electrical signals. These signals trigger contractions in cardiac muscle — in other words, they cause the heart muscles to squeeze.

Electricity keeps the heart pumping at a steady pace and can make it speed up or slow down. Electrical pulses travel around the heart through a network of specialized groups of cells called nodes. Interruptions to the flow of electricity through these nodes can cause an irregular heartbeat, a condition known as arrhythmia.

The heart's electrical signals start in the heart's "pacemaker," a specific node of cells. Located in the upper right atrium, the crescent-shaped pacemaker measures about half an inch (13.5 millimeters) long in adults. It typically generates an electrical pulse at regular intervals, about 60 to 100 times per minute. That causes the atria to contract.

This electrical signal from the pacemaker then travels to another node on the same side of the heart but slightly lower down. Once the atria empty blood into the ventricles, this second node passes the electrical pulse to nerves around the bottom of the heart. These fibers forward the signal to the ventricles. The ventricles then contract, pumping blood out to the body.

How many times does the heart beat in a day?

Heart rate is measured in beats per minute, or bpm. As the body performs different tasks throughout the day, the heart rate adjusts automatically as needed with the help of the brain and nerves.

The term "resting heart rate" describes how quickly the heart beats during normal activity and relaxation. A person's physical activity levels, emotions, age, fitness and overall health can affect their heart rate. Heart rates are typically a bit lower during sleep.

A healthy adult normally has a resting heart rate of 60 to 100 bpm. Newborns up to 4 weeks old have a much faster resting heart rate of 100 to 205 bpm. Children ages 5 to 12 years have a resting heart rate of 75 to 118 bpm, and people 13 and older have the same resting heart rate as adults.

On average, an adult heart beats more than 100,000 times per day, even when just at rest. All that pumping sends over 1 gallon (5 liters) of blood traveling through the circulatory system. In a year, an adult's heart beats about 37 million times. By the time a person reaches their late 70s, they've logged nearly 3 billion heartbeats.

What can make your heart speed up?

It is perfectly normal for a person's heart rate to speed up or slow down, depending on what they are doing. Activities that make the body work harder cause the heart rate to increase. During exercise, muscles need more oxygen — up to four times as much as they require while at rest. In response, the heart beats faster. This moves oxygenated blood to hardworking muscles more quickly. The more intense the exercise or activity, the quicker and more forcefully the heart pumps.

Other activities can also affect your heart rate. After you eat, your heart pumps harder to send more oxygen to your digestive system to help break down the food. Drinking caffeine (for example, in coffee, soda or some teas) causes the body to release a hormone called norepinephrine, which can make the heart beat faster. In pregnant people, whose bodies are working much harder to support a growing baby, resting heart rate can increase by about 10 to 20 bpm.

Intense emotions and stress can also increase a person's heart rate. When someone is nervous, angry, frightened, frustrated or upset, the body releases stress hormones, such as adrenaline and cortisol. These hormones cause the person's heart to beat faster and also speed up their breathing. Known as the "fight or flight" response, this effect evolved in our ancient ancestors to help protect them from harm. A faster heartbeat prepares the body to defend itself or escape danger.

What happens during a heart attack?

A heart attack is a life-threatening medical emergency. It occurs when arteries that supply the heart with blood and oxygen are blocked, often by a buildup of fats and cholesterol, a wax-like substance.

Once a blockage cuts off blood flow to the heart, its tissues starts to die. Severe heart attacks can cause blood vessels around the heart to burst and kill even more heart muscle tissue.

As a heart attack progresses, the pressure in the heart increases. This causes fluid to build up in the lungs, leading to shortness of breath. Meanwhile, tissues in other parts of the body don't get enough oxygen, causing muscle pain that shoots from the chest to the arms, and then to the shoulders, jaw, neck or back. The lack of blood flow can also lead to dizziness, belly pain, nausea or vomiting. Reduced blood flow may cause swelling in the ankles or feet, too.

A feeling of tightness or pressure in the chest could be the first sign of a heart attack. However, the symptoms can vary greatly depending on the person. About half of heart attacks include belly pain. For women, the first symptoms of a heart attack are more likely to be trouble breathing, an upset stomach, or pain somewhere other than the chest.

Some heart attacks are "silent," meaning they don't cause obvious symptoms as they're happening. But they can still cause problems down the line.

Heart pictures

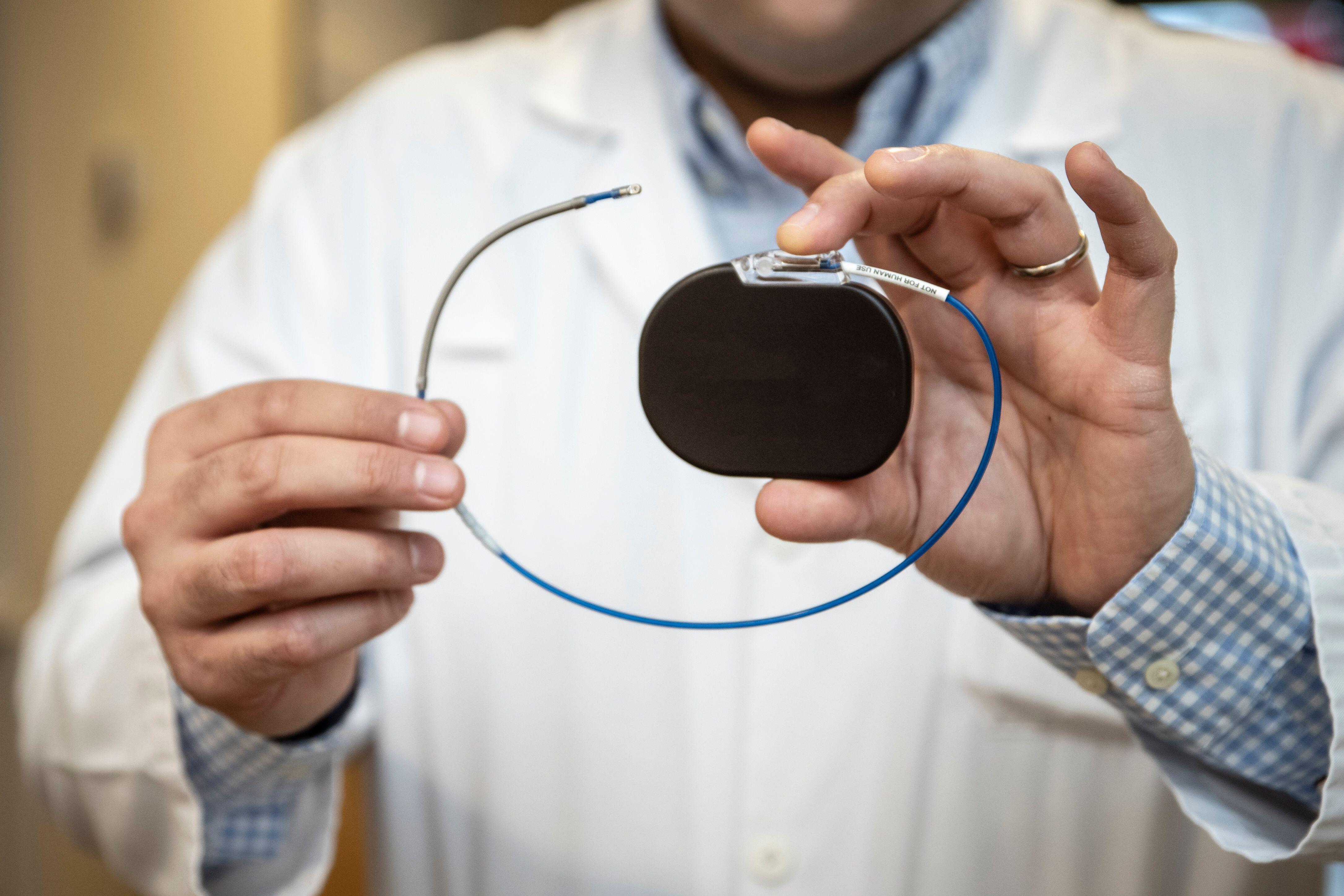

Battery-powered pacemaker

A pacemaker is a device that uses electricity to fix an irregular heartbeat. A pacemaker is inserted via surgery and runs on batteries. It sends electrical signals to the heart to prevent it from beating too slowly or out of rhythm.

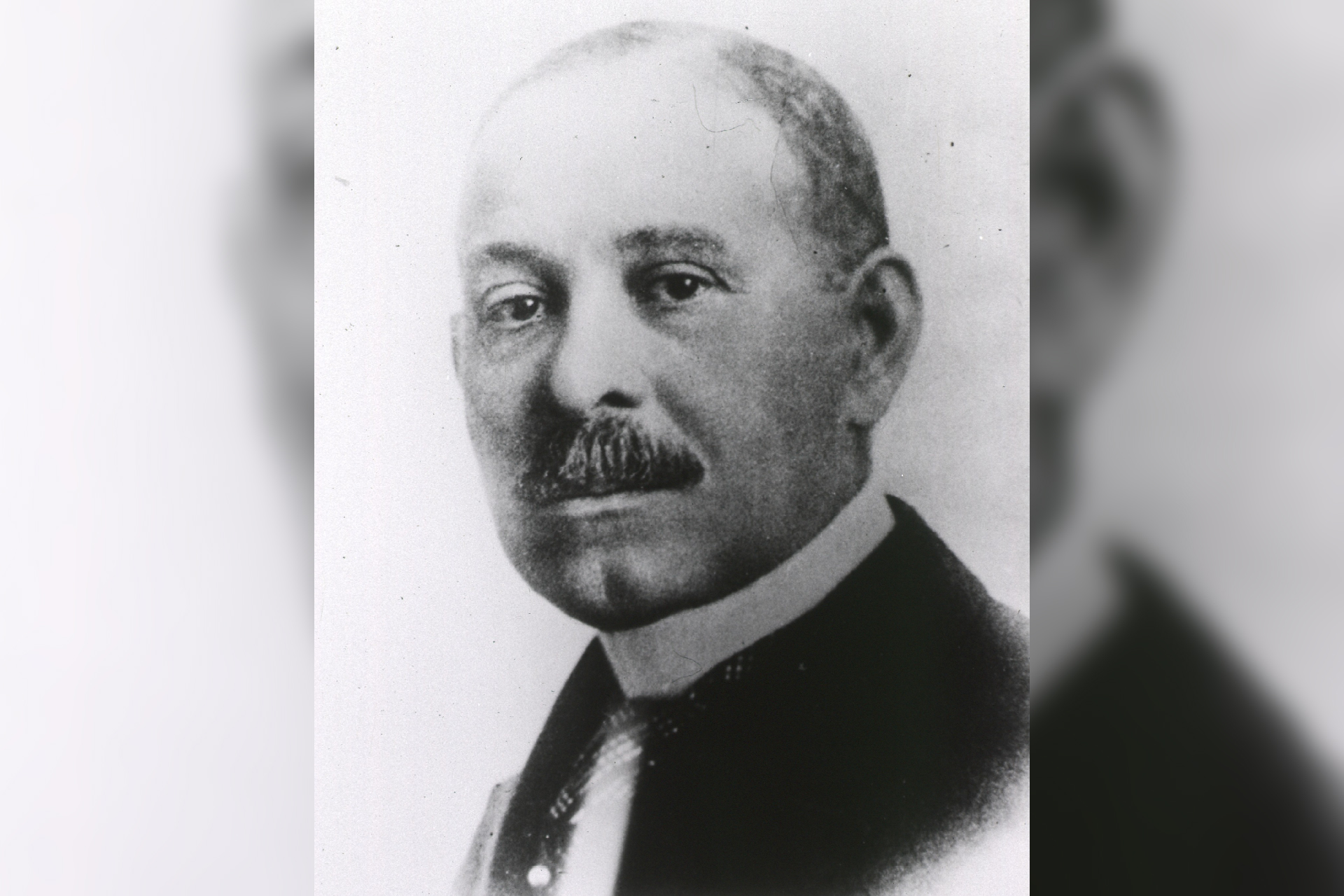

Pioneering heart surgeon

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams (1856-1931) was the first Black cardiologist (heart doctor). In 1893, he became the first doctor to perform a successful open-heart surgery. Williams later co-founded the National Medical Association, a professional organization for Black medical workers.

Hearing the heart

Health care providers use stethoscopes to listen to the heart and other internal organs. These devices allow doctors to hear the heart beating and blood flowing, which can help them detect problems with the heart.

Heart health in space

Studying how astronauts' arteries change in space can help scientists understand how a person's heart changes as they get older

Discover more about the heart

- How many times does a heart beat in a day? What about in a lifetime?

- 9 heart disease risk factors, according to experts

- What happens during a heart attack?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works. She is the author of the book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control," published by Hopkins Press.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.