T. Rex's Smaller Cousin Ate Like a Falcon, Study Finds

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

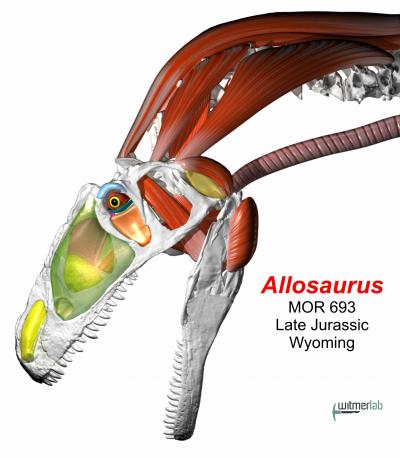

A smaller cousin of the Tyrannosaurus rex, called Allosaurus, may have fed on its prey in a fashion similar to modern-day falcons, a new study finds.

Researchers at Ohio University in Athens found that while a T. rex whips its head from side to side to gorge on its victims, the Allosaurus — a theropod that lived about 150 million years ago in the late Jurassic period — may have been a more dexterous hunter, using its neck and body to tug flesh from carcasses, the same way a falcon does.

"Apparently one size doesn't fit all when it comes to dinosaur feeding styles," Eric Snively, a paleontologist at Ohio University and lead author of the new study, said in a statement. "Many people think of Allosaurus as a smaller and earlier version of T. rex, but our engineering analyses show that they were very different predators." [Image Gallery: The Life of T. Rex]

The study's findings were published online today (May 21) in the journal Palaeontologia Electronica.

Build-a-dinosaur

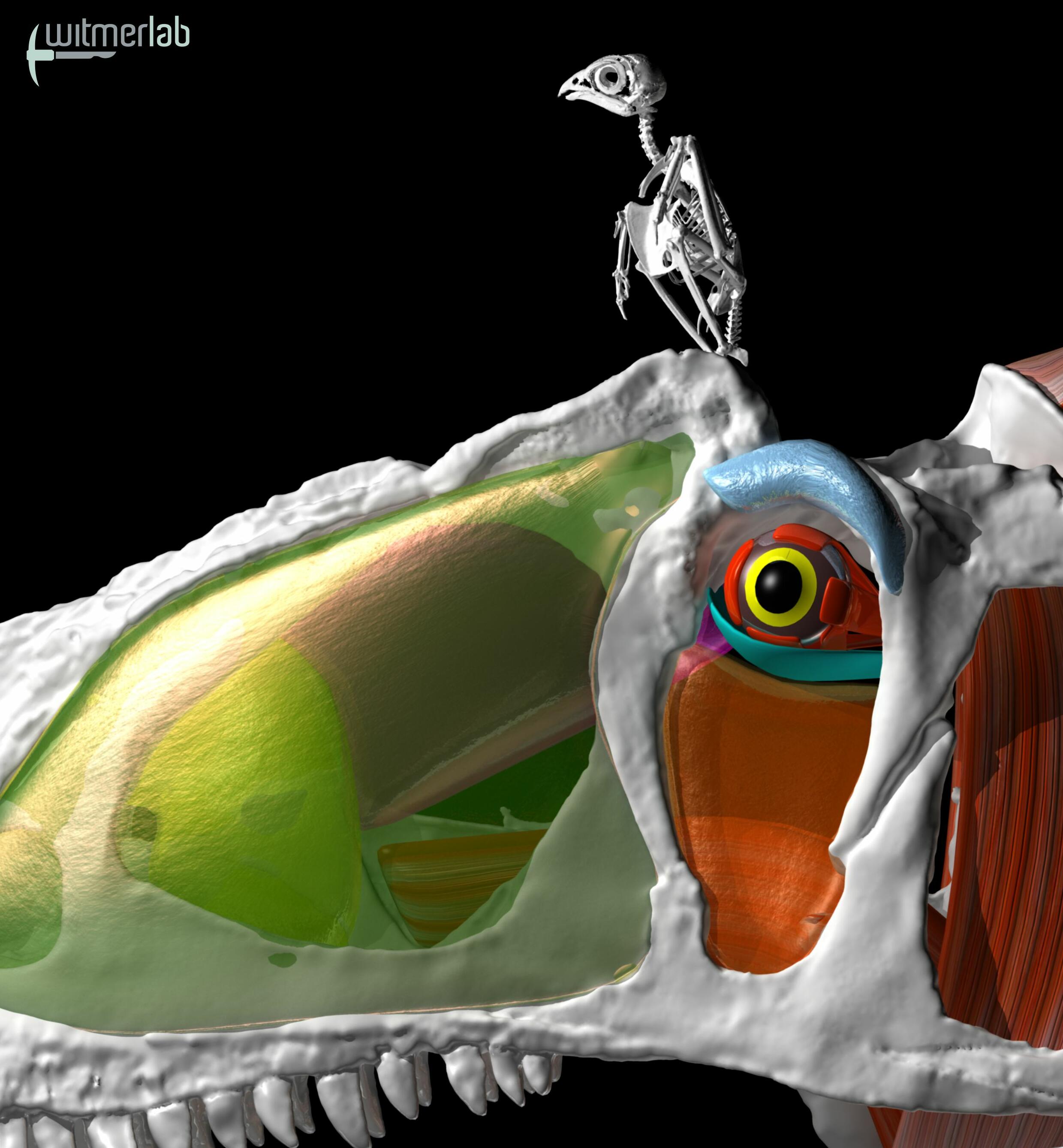

To study the dinosaur's feeding technique, Snively and his colleagues ran sophisticated computer simulations of an Allosaurus' head and neck movements using a high-resolution cast of the dinosaur's skull and neck, plus CT scans of its bones. By combining dinosaur anatomy with mechanical engineering and computer visualization, the researchers were able to experiment with how the Allosaurus attacked prey, fed, or simply looked around.

"The engineering approach combines all the biological data — things like where the muscle forces attach and where the joints stop motion — into a single model," study co-author John Cotton, a mechanical engineer and assistant professor in the Russ College of Engineering and Technology at Ohio University, said in a statement. "We can then simulate the physics and predict what Allosaurus was actually capable of doing."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers worked with anatomists to "re-flesh" their 3D Allosaurus computer model. In the process of building these neck and jaw muscles, air sinuses, and other soft tissues, the researchers found an unusually placed neck muscle, called longissimus capitis superficialis.

In most other predatory dinosaurs, including the T. rex, this neck muscle stretches from the side of the neck to a bony structure on the back outer corners of the skull, the researchers said.

"This neck muscle acts like a rider pulling on the reins of a horse's bridle," Snively explained. "If the muscle on one side contracts, it would turn the head in that direction, but if the muscles on both sides pull, it pulls the head straight back."

A different kind of predator

With the Allosaurus, however, the researchers found that the longissimus muscle was attached much lower on the skull, which would have equipped the dinosaur with a different set of head and neck movements.

"Allosaurus was uniquely equipped to drive its head down into prey, hold it there, and then pull the head straight up and back with the neck and body, tearing flesh from the carcass … kind of like how a power shovel or backhoe rips into the ground," Snively said.

In today's modern world, this same feeding technique is seen with small falcons, the researchers said.

The scientists also found that the Allosaurus had a relatively light skull, which likely made it a more dexterous predator, compared with T. rex, with its massive, toothy skull.

"Allosaurus, with its lighter head and neck, was like a skater who starts spinning with her arms tucked in, whereas T. rex, with its massive head and neck and heavy teeth out front, was more like the skater with her arms fully extended … and holding bowling balls in her hand," Snively said. "She and the T. rex need a lot more muscle force to get going."

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus