All Yours: 10 Least Visited National Parks

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Room to Breathe

Now that summer is here and winter is a distant memory, it's time to get outside and enjoy the sunshine. But skip the cliché trip to the Grand Canyon and its 4.3 million yearly visitors and instead check out one of the equally stunning parks that get far less attention from fellow vacationers.

Here's a rundown of some of the hidden gems of the U.S. park system that will still satisfy your inner explorer, and don't require an expedition team to reach. Each park is packed with enough science and natural beauty to stimulate your mind and soul, but each has fewer than 100,000 visitors per year.

City of Rocks National Reserve, Idaho

96,649 visitors per year

Just like the name implies, City of Rocks National Reserve is dominated by granite spires and sculptured rock formations up to hundreds of feet high. Some of the granite towers are over 60 stories tall and 2.5 billion years old. Over 500 rock climbing routes have been mapped out along the rocks smooth faces.

The uplifted and eroded rocks are like an open window into the Earth where visitors and scientists alike can view tectonic events that raised the mountainous interior of the western United States along with weather events that shaped the landscape.

Visitors can also still see remnants of the California Trail wagon ruts and signatures in axle grease that are found in the area that was once a landmark for California-bound emigrants.

Web site: http://www.nps.gov/ciro

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

More info: 200 miles (322 km) southeast of Boise in Almo, Idaho 83312-0169.

Phone: (208) 824-5519.

Cumberland Island National Seashore, Georgia

77,588 visitors per year

A trip to Cumberland Island will take you back in time to the days of barrier islands along the Atlantic coast. The island is Georgia's largest at 17.5 miles (28 km) long and is the southernmost barrier island. Cumberland is home to pristine beaches and dunes, maritime forests, freshwater lakes, and even the remains of centuries of human life. Cumberland has the oldest known ceramics in North American and shell middens dumps for domestic waste from early natives.

The island's salt marshes contain dense strands of herbs and grasses that are able to withstand the harsh, salty water and trap sediments crucial to the aquatic food web. Gnarled live oak trees covered with a Spanish moss canopy paint an idyllic Southern Gothic image on the island. Wild horses one of the most well-known features of Cumberland roam the island's 36,415 acres (147 sq km). Cumberland Island is a crucial stopover for many birds migrating on the transatlantic migratory flyaway. There are no bridges to Cumberland; ferries make only two trips per day, and the number of visitors is capped at 300 per day.

Web site: http://www.nps.gov/cuis

More info: 300 miles (482 km) southeast of Atlanta in St. Marys, Ga. 31558-0806.

Phone: (912) 882-4335.

Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument, Colorado

64,251 visitors per year

Florissant National Monument is a 6,000 acre (24 square km) fossil hunter's delight. The park is a treasure trove of paleontological history containing some of the world's richest plant and insect fossils preserved 8,400 feet (2.5 km) above sea level by volcanic ash from the Thirtynine mile volcanic area.

Over 50,000 specimens of more than 1,700 different species have been described, mostly plants and insects, but also some of the largest-diameter petrified Sequoia trees in the world. The world's only known petrified trio of redwood trees is found at Florissant. The fossils are relatively young, geologically speaking. Most date to the Eocene Epoch 34 million years ago.

Those that venture to Florissant will also find eagles, Tiger salamanders, mountain lions and beetles.

Web site: http://www.nps.gov/flfo

More info: 100 miles (161 km) southwest of Denver in Florissant, Colo. 80816.

Phone: (719) 748-3253.

Chiricahua National Monument, Arizona

60,851 visitors per year

The Chiricahua Mountain Range shoots out of the Arizona desert like trees in a forest. This "Wonderland of Rocks" was created millions of years ago by volcanic activity, but the Chiricahua Mountains are now an inactive volcano range stretching 20 miles (32 km) wide and 40 miles (64 km) long.

The parks' pinnacles, columns, spires, and balanced rocks some rising hundreds of feet into the air are the remains of violent geological activity that continued for many millions of years. A paved, scenic 8-mile (13-km) drive and 17 miles (27 km) of hiking trails will keep your legs and eyes busy. The Chiricahua Mountains are called a sky island because they rise like islands out of the surrounding grassland "sea." Plants and animals from the Rocky Mountains, Sierra Madre Mountains, Sonoran and Chichuahuan Deserts all converge here.

Black bears lurk in the park, nibbling on the pretty red bark called manzanita, which is Spanish for little apple. Coatimundi, a mammal in the raccoon family, and the park's birds also snack on these little apples. Other animals prowling the Chiricahua include mountain lions, Arizona white-tail deer, black-tail rattlesnakes and pink winged moths.

Web site: http://www.nps.gov/chir

More info: 230 miles (370 km) southeast of Phoenix in Willcox, Ariz. 25643.

Phone: (520) 824-3560.

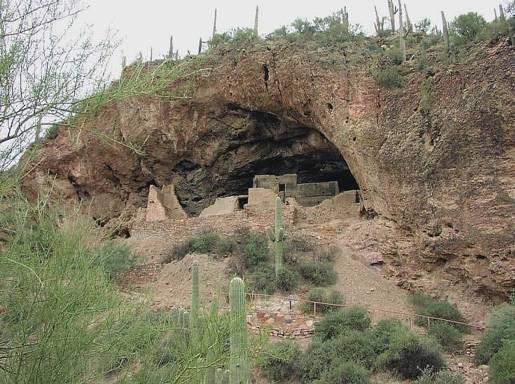

Tonto National Monument, Arizona

60,533 visitors per year

Tonto is home to exquisitely preserved cliff dwellings, which were occupied in the 13th and 14th centuries when the Solado Indians called this area home. The monument is not the most visitor-friendly it's 4,000 feet (1,219 meters) closer to the hot Arizona sun than at sea level, so visitors usually venture there during the winter, when the weather is more bearable.

The Solado lived in the arid Tonto Basin, where only 15 inches (38 centimeters) of rain fall in a year in this part of the Sonoran Desert. The Solado soon began perching thousands of feet up to avoid the crowded Salt River valley below.

Tonto is home to some of the most spectacular cacti species, including the vibrantly colored Cane Cholla cactus. Some of the oldest Douglas Fir trees in North America whose growth has been stunted and gnarled by the extreme conditions are found in the basaltic volcanic rocks on the park's west side. Many are hundreds of years old. The wildlife of the area is equally vibrant: Black bears, cougars, coyotes, foxes and rattlesnakes all prowl the Tonto Basin.

Web site: http://www.nps.gov/tont

More info: 100 miles (160 km) northeast of Phoenix in Roosevelt, Ariz. 85545.

Phone: (520) 467-2241.

Dry Tortugas National Park, Florida

52,011 visitors per year

Dry Tortugas National Park, a cluster of seven islands composed of coral reefs and sand, is a 68-mile (112.9-km) boat or sea plane trip west of Key West, into the Gulf of Mexico. The park is actually closer to Cuba than it is to the American mainland.

Dry Tortugas is home to Fort Jefferson, a giant pentagon-shaped brick fortress built in 1846 to control the Florida Straits. The Dry Tortugas islands are in a constant state of flux. The shorelines are constantly changing because of the erosive effects of tropical storms. Entire islands have been known to disappear or reform following the passage of particularly violent hurricanes.

The name Dry Tortugas comes from the turtles that crawl around the area "Las Tortugas" is Spanish for "The Turtles." Loggerhead, green, hawksbill and leatherback sea turtles can all be seen here.

The park is home to unique wildlife that depend on the islands for survival. The Sooty Tern a type of sea bird has its only regular nesting site in the United States on Bush Key, next to Fort Jefferson. Giant sea turtles depend on the park's protected beaches to bury their clutches of eggs. In total, there are seven other threatened species and nine endangered species that visit Dry Tortugas at least occasionally.

Web site: http://www.nps.gov/drto

More info: 70 miles (113 km) west of Key West, Fla. 33041-6208.

Phone: (305) 242-7700.

Katmai National Park and Preserve, Alaska

43,035 visitors per year

Katmai is home to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes a stunning deep ash flow deposited by Novarupta Volcano covering forty square miles (100 square kilometers) and plunging as deep as 700 feet (213 meters). The volcano's cataclysmic 1912 eruption is essentially a living laboratory of volcanic blast. Today you can walk among the thousands of fumaroles openings in the Earth's crust that once vented steam from their ash. Most of these fumaroles have cooled, but several active ones remain. The eruption was the largest eruption of the 20th century. Ash from the eruption traveled to Seattle, Virginia, and even as far away as Africa.

The park's rugged shoreline and iconic American wildlife such as the brown bear and bald eagle that call Katmai home are popular draws. Brown bears are North America's largest land predators, feasting on the state's salmon runs. And eat they do; mature male bears can weigh up to 900 pounds!

Web site: http://www.nps.gov/katm

More info: 250 miles (400 km) southwest of Anchorage in King Salmon, AK 99613.

Phone: (907) 246-3305.

Kalaupapa National Historical Park, Hawaii

30,654 visitors per year

There's a pretty good reason Kalaupapa National Historic Park is little visited it was home to the people of Hawaii afflicted with Hansen's disease, popularly known as leprosy, from 1866 until 1969. While leprosy is not a public health threat any more, at one time, over 1,200 people were in exile at this island prison known as the Kalaupapa Leper Settlement.

Leprosy is caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium leprae and leaves visible scaring skin lesions. The disease is transmitted through prolonged close contact with droplets from the nose and mouth of those already infected. In the late 1940s sulfone drugs were discovered and some of the physical barriers between patients and non-patients were removed. To visit the island is to travel back to a time when mysterious medical diseases were treated by quarantining and preaching to the infected.

Aside from the leper colony settlements, visitors to Kalaupapa and Hawaii the most isolated major island chain in the world will experience an abundance of native plant and animal species. Around 95 percent of these native species are found nowhere else in the world, including the endemic haha and alani plants. Minimal human interference on the island has created an ideal spot for monk seals to give birth. More than five monk seal pups were born on Kalaupapa beach in recent years.

Web site: http://www.nps.gov/kala

More info: 35 minute flight from Honolulu, HI. Kalaupapa, Hawaii 96742-2222.

Phone: (808) 567-6102.

Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument, Idaho

27,263 visitors per year

The Snake River in Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument has fossils embedded in sediment on its banks. The fossils allow a glimpse of life before the last Ice Age to see the earliest appearance of modern flora and fauna.

Stand on the Snake River Overlook for views of the bluffs that are over 600 feet (180 m) high. The bluffs are layers of sediments, called strata sands, silts, and clays deposited by the flooding of the rivers flowing into ancient Lake Idaho more than 3 million years ago.

Hagerman is home to the largest concentration of Hagerman Horse fossils in North America 30 complete horse fossils in total. The fossil beds are also the world's richest late Pliocene epoch (3 to 4 million years old) fossil deposits with over 200 species of plants and animals represented. Hagerman paleontologists have uncovered some unusual fossils over the years. Once they found a skeleton of a suckerfish, a pond turtle fossilized in its shell, a jaw with several teeth from a pocket gopher and a jaw from a creature that was a member of the weasel family.

Web site: http://www.nps.gov/hafo

More info: 100 miles (161 km) southeast of Boise in Hagerman, Idaho 83332-0570.

Phone: (208) 933-4100.

Russell Cave National Monument, Alabama

24,087 visitors per year

Prehistoric humans called this area of north Alabama home for over 10,000 years. Russell Cave is the oldest rock shelter that was once used for a home in the eastern United States, and it houses the most complete record of prehistoric cultures in the Southeast. This record provides clues about the lives of early North American people from about 6,500 B.C. to 1650 A.D. The stages of human civilization in southeastern America before European contact are termed Paleo, Archaic, Woodland, and Mississippian. Most of the prehistoric humans at Russell Cave lived during the Archaic stage.

The cave opening faces the east to avoid the cold north wind and let in the morning sun. Water, animals for hunting and rocks for carving weapons were all abundant nearby. The cave probably housed an extended family of about 15 to 30 people.

The rock that forms Russell Cave is over 300 million years old and was created at the bottom of the inland sea that once covered the region. Carbon deposits such as skeletons and shells were transformed to limestone by the pressure of water, sand, and mud over millions of years.

Web site: http://www.nps.gov/ruca

More info: 37 miles (60 km) southwest of Chattanooga, Tenn. in Bridgeport, Ala. 35740.

Phone: (205) 495-2672.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus