Inbreeding Common in Early Humans, Deformed Skull Suggests

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Inbreeding may have been a common practice among early human ancestors, fossils show.

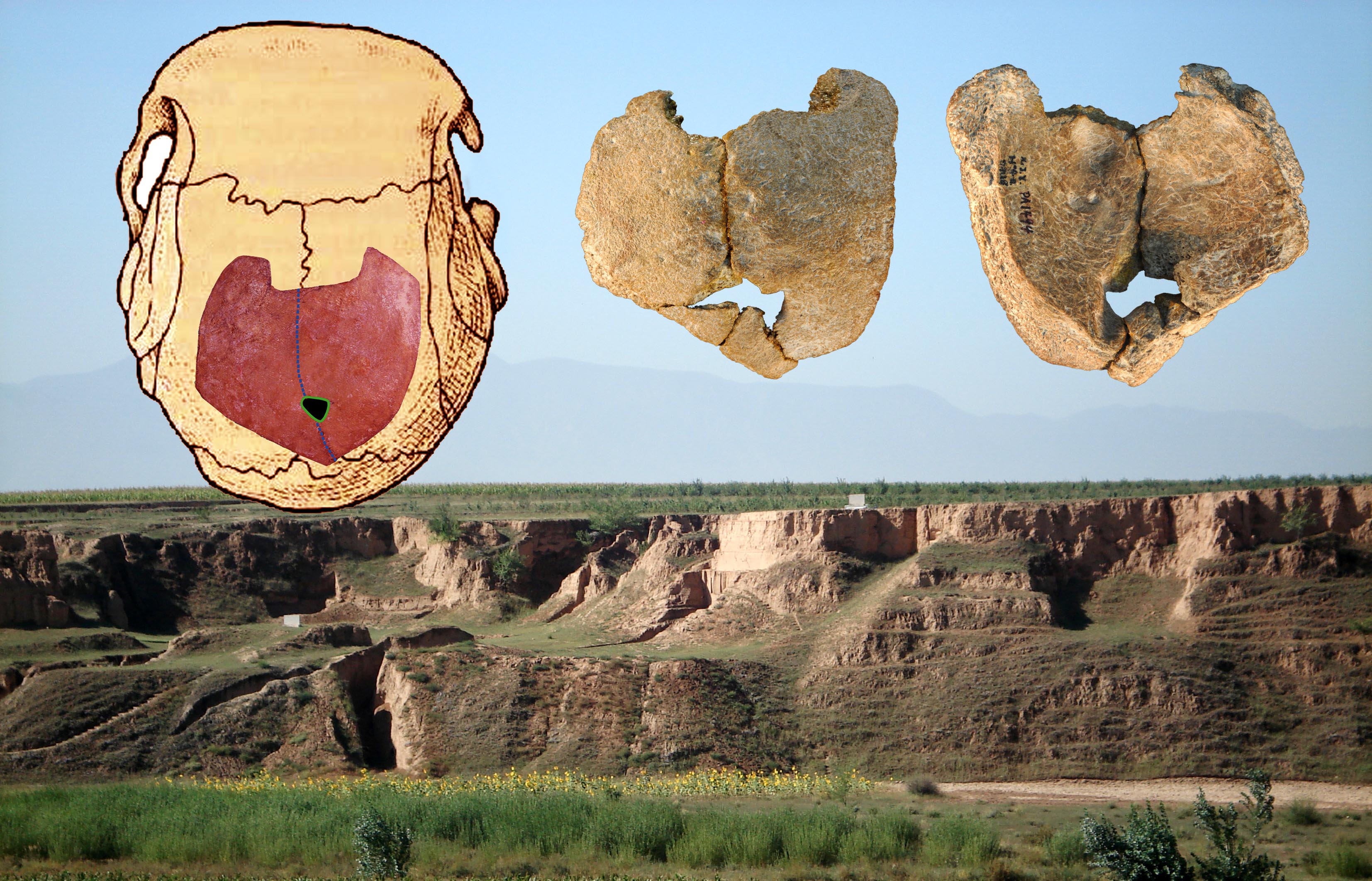

The evidence comes from fragments of an approximately 100,000-year-old human skull unearthed at a site called Xujiayao, located in the Nihewan Basin of northern China. The skull's owner appears to have had a now-rare congenital deformity that probably arose through inbreeding, researchers report today (March 18) in the journal PLOS ONE.

The fossil, now dubbed Xujiayao 11, is just one of many examples of ancient human remains that display rare or unknown congenital abnormalities, according to the researchers. "These populations were probably relatively isolated, very small and, as a consequence, fairly inbred," study leader Erik Trinkhaus, an anthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis, told LiveScience.

The human skull fossil has a hole at its top, a disorder known as an "enlarged parietal foramen," which matches a modern human condition of the same name caused by a rare genetic mutation. The genetic abnormalities obstruct bone formation by preventing small holes in the prenatal braincase from closing, a process that normally occurs within the first five months of the fetus' development. Today, these mutations are rare, occurring in only about one of every 25,000 human births. [The 9 Most Bizarre Medical Conditions]

The skull appears to be from an individual who lived into middle age, indicating the abnormality was not lethal. The skull deformity can sometimes lead to cognitive deficits, but the age of the individual suggests any deficits probably would have been minor, Trinkhaus said.

The skulls of humans from the Pleistocene epoch (roughly 2.6 million to 12,000 years ago) show an unusually high occurrence of genetic abnormalities like this skull-hole deformity, the researchers found. Scientists have seen these abnormalities in fossils from the time of early Homo erectus to the end of the early Stone Age.

Such a high frequency of genetic abnormalities in the fossil record "reinforces the idea that during much of this period of human evolution, human populations were very small" and, consequently, likely inbred, Trinkhaus said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Still, "it remains unclear, and probably un-testable, to what extent these populations were inbred," the researchers noted in their study.

Yet if such small, inbred populations did exist, it would invalidate many of the genetic inferences about when humans split off from the tree of life, Trinkhaus said, because these inferences assume large, stable populations.

Follow Tanya Lewis @tanyalewis314. Follow us @livescience, Facebook or Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus