Head Lice: Symptoms, Treatment and Prevention

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

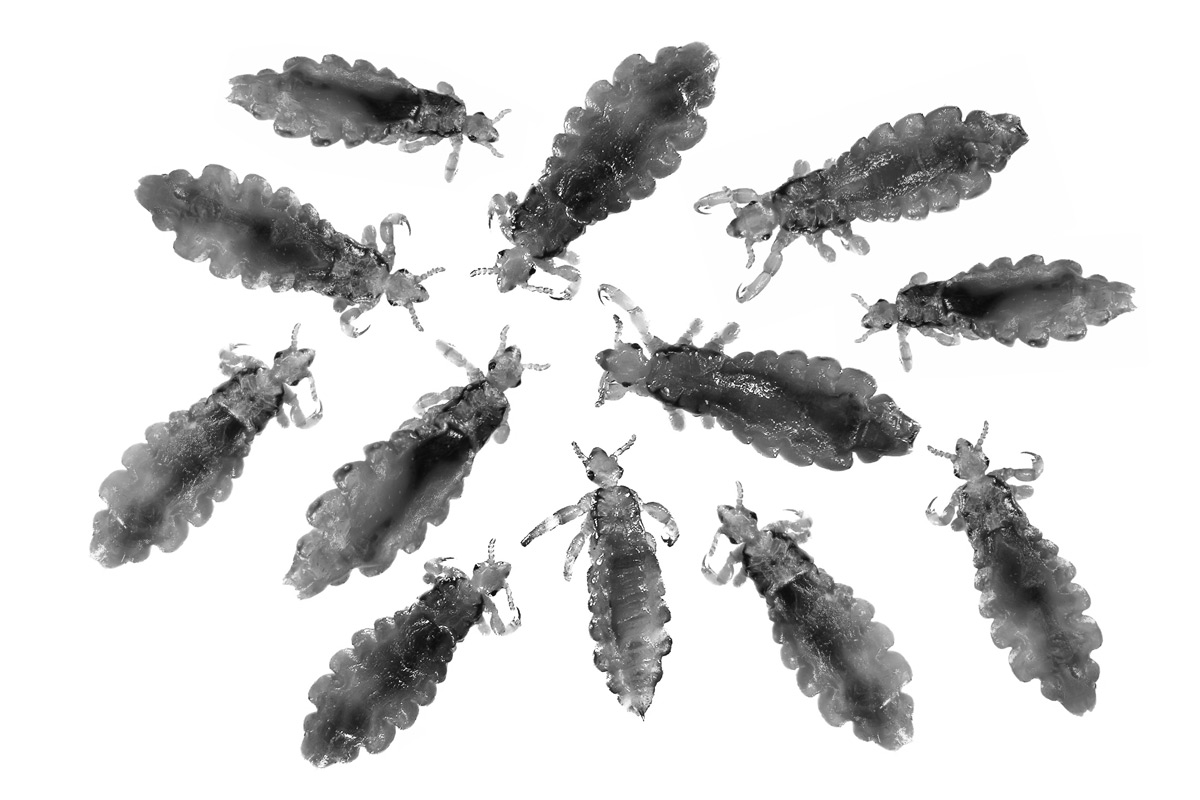

A sesame seed-size parasite that feeds on human blood, the head louse (Pediculus humanus capitis) is a nuisance known around the world. These tiny insects infest human hair and can also sometimes be found in the eyebrows and eyelashes.

An estimated 6 million to 12 million head lice infestations occur each year in the United States among children ages 3 to 11, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). While school-age kids are believed to be those most commonly affected by lice, it's possible for people of any age to become infested with these flightless pests.

Signs & symptoms

Some people with lice never realize they're infested. However, there are several telltale signs that the bugs are present on the scalp, according to the Mayo Clinic. These include:

- A ticklish feeling on the scalp or neck.

- An itchy scalp (the result of an allergic reaction to the bug's saliva).

- Small red bumps on the scalp, neck and shoulders.

- The presence of lice on the scalp.

- The presence of nits (lice eggs) on shafts of hair.

- Difficulty sleeping, which can lead to irritability.

Some people with lice may also develop sores on their scalp. Such sores are likely the result of bacteria from the person's own body infecting an opening in the skin made by scratching, according to the CDC. Some people may scratch their scalps raw due to the itch and cause skin infections, said Margaret Khoury, a pediatric infectious disease specialist with Kaiser Permanente.

Because head lice are not known to spread disease in the United States, they should not be considered a "medical or public health hazard," according to the CDC. Lice are also not indicative of poor hygiene, Khoury said. However, several studies conducted in recent years in other areas of the world, including Africa, suggest that certain species of head lice are capable of carrying infectious disease.

One study, outlined in the May 2013 issue of the journal Emerging Infectious Disease, found that head lice in the Democratic Republic of the Congo could spread plague. And another study, outlined in the same journal in May 2014, found that human body lice carrying a pathogen that can cause trench fever — among other diseases — can also inhabit human hair.

Diagnosis & tests

The best way to confirm an active lice infestation is to find a live louse on the head, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Because lice move quickly and avoid light, it's best to check for them after wetting the hair, which some experts say slows the insects down.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The most effective way to check for lice is to use a louse comb, according to the AAP. In a study published in 2001 in the journal Pediatric Dermatology, researchers found that using a louse comb was four times more effective than simply doing a visual check of the scalp for lice and that checks with the louse comb could be performed two times faster than visual checks.

Dandruff, dirt and other common debris found in the hair are commonly confused for lice, according to the CDC. Therefore, the best person to perform a head check for lice may be someone trained to identify these parasites, like a health care provider or school nurse.

If no live lice are found on the scalp, finding nits firmly attached to the hair shaft within a quarter inch of the scalp may indicate that a person is infested, according to the CDC. However, it's important to confirm that an infestation of head lice is actually active before pursuing treatment, according to the AAP.

Nits from previous lice infestations can remain attached to hair shafts, even if no live lice are present on the scalp. To make future diagnoses of lice easier, as well as to ensure that no living nits remain in the hair, all nits should be removed from the hair, even after the infestation has been treated, according to the National Pediculosis Association (NPA), a nonprofit organization that does not support the use of insecticides to treat lice.

Treatment & medication

The ideal treatment is one that is "completely safe, free of harmful chemicals, readily available without a prescription, easy to use and inexpensive," according to the AAP.

There are several treatment options for those with head lice, including shampoos and creams that contain pediculicides, or insecticides that kill lice, as well as combing the hair with a louse comb that removes lice and nits. Neither one of these treatments options is 100 percent effective at removing all lice or nits from hair.

When choosing a treatment for lice, people should be aware that, in some areas of the United States and Europe, lice have developed resistance to some of the most common pediculicides found in both over-the- counter and prescription lice treatments. The CDC recommends consulting with a doctor or pharmacist to determine what treatments are best to use. Khoury, along with the AAP, recommends that lice should first be treated with an over-the counter medication first and move on to prescription medication if the over-the-counter treatment is ineffective or there are potential allergies.

If no resistance to insecticides is suspected, the AAP recommends using products that contain pediculicides known as pyrethrins or the chemical permethrin. However, these chemicals are known to be toxic to humans and should be used with caution, according to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

"Permethrin has been the most studied pediculicide in the United States and is the least toxic to humans," Khoury told Live Science. She added that while pyrethrins are manufactured with natural extracts from chrysanthemum and have extremely low toxicity, those with known allergies to the flower, similar plants, or ragweeds can develop allergic reactions.

If you choose to use a chemical treatment for lice, be sure to follow dosing instructions correctly and consult with your health care provider if you plan to use these treatments on a child under age 2, according to the CDC. Khoury recommended making sure that you pay special attention to the directions on both over the counter and prescribed medications, including how long the medication should be left in, how it should be washed out, how often doses should be given, approved ages, and any allergy or chemical information.

To minimize exposure to the insecticides found in lice treatment shampoos, rinse the scalp and hair well with cool water after applying these products and try to avoid exposing skin (other than the skin on the scalp) to these products, according to the Canadian Pediatric Society. If you are bathing a child, rinse the treatment out of the hair over a sink. Do not place the child in a bath as the hair is being rinsed.

If the lice in your area are resistant to permethrin and pyrethrins, the AAP recommends using a product containing 0.5 percent malathion, another insecticide that is rubbed into the hair and scalp. Malathion has not been deemed safe or effective to use in children younger than 6, and the product is not safe to use in children younger than 24 months, according to the AAP. Neither malathion nor permethrin and pyrethrins effectively kill all of the egg stages of lice. This means that these chemicals need to be reapplied to the scalp seven to 10 days after the initial treatment.

There are also several other chemicals that can be used to treat lice, including lindane, which is available as a cream or a shampoo. This chemical has been known to cause severe seizures in children and cannot be prescribed to individuals who weigh less than 110 pounds (49.9 kilograms), according to the AAP. Other chemical treatments have also been linked to dangerous side effects in children, which is why organizations such as the NPA do not recommend the use of chemical treatments for lice.

The manual removal of lice recommended by the NPA can be performed using the same type of fine-toothed louse comb used to check the scalp for lice. Louse combs can be used on wet or dry hair, though some experts suggest that combing out lice and nits is easier on wet hair. Some people may also wish to use a conditioner before combing out the hair, according to the NPA.

Preventing the spread

Once a case of head lice is confirmed, the best way to prevent spread is to thoroughly treat and get rid of the head lice. Avoiding head-to-head contact as much as possible will also help curb an infestation, according to the CDC.

Although a less-frequent cause of spread, lice can travel from one person to another via shared clothing and accessories, such as hats, brushes and hair accessories. People with lice should avoid sharing these items with others, and should also avoid sharing a bed with siblings or friends. Though rare, lice can spread from person to person through infested upholstery or bed linens.

Once a person is treated for lice, all bedding, upholstered furniture, carpets, hairbrushes and other items that had direct contact with that person's scalp should be thoroughly cleaned, according to the CDC. Clothes and bedding can be washed in hot water, hairbrushes and hair accessories can be boiled, rugs or other non-washable items can be dry cleaned, and items that can't be washed or dry cleaned can be stored in airtight containers for several weeks to ensure that live lice and nits do not survive.

Finally, vacuum carpeted floors and clean all furniture to prevent the spread of lice to others. Measures such as fumigation are not necessary and should be avoided, according to the CDC.

Households with pets do not have to worry about lice infestations moving to the family cat or dog. The CDC says that head lice do not live on pets (lice are species-specific) and are not involved with the spreading of an infestation.

While some schools follow a "no-nit" policy that requires children with lice to stay at home, the AAP does not recommend such policies. The NPA, however, supports stringent no-nit policies in schools.

Additional reporting by Rachel Ross, Live Science Contributor.

Additional resources

- Learn more about head lice, including risk factors, treatment and prevention, at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- The National Pediculosis Association is a nonprofit organization that provides news, resources and other information about treating head lice.

- Read more about the causes, symptoms and treatment of head lice, as well as images of head lice infestation, at the National Library of Medicine.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus