Evolution's Bite: Ancient Armored Fish Was Toothy, Too

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A set of jaws can invoke visions of deadly toothy sharks, and now scientists find the earliest fish with chops — the ancestors of all jawed creatures with backbones — were also armed with teeth, researchers say.

The evolution of teeth and jaws in vertebrates — animals with backbones — about 420 million years ago is considered to be a key factor behind their success, making everything from a T. rex's razor-sharp teeth to a dwarf mammoth's grinding molars possible. However, whether jaws or teeth came first remains uncertain.

"It has long been thought that the first jawed vertebrates were gummy — [they had] jaws without teeth, capturing prey by suction-feeding," researcher Philip Donoghue, a paleontologist at the University of Bristol in England, told LiveScience.

To investigate this mystery, Donoghue and his colleagues analyzed 370-million-year-old fossils of a diverse and extinct group of armored fish known as placoderms, the first-known jawed vertebrates. These marine specimens were collected in Australia by researchers at the Natural History Museum London and from the Western Australia Museum.

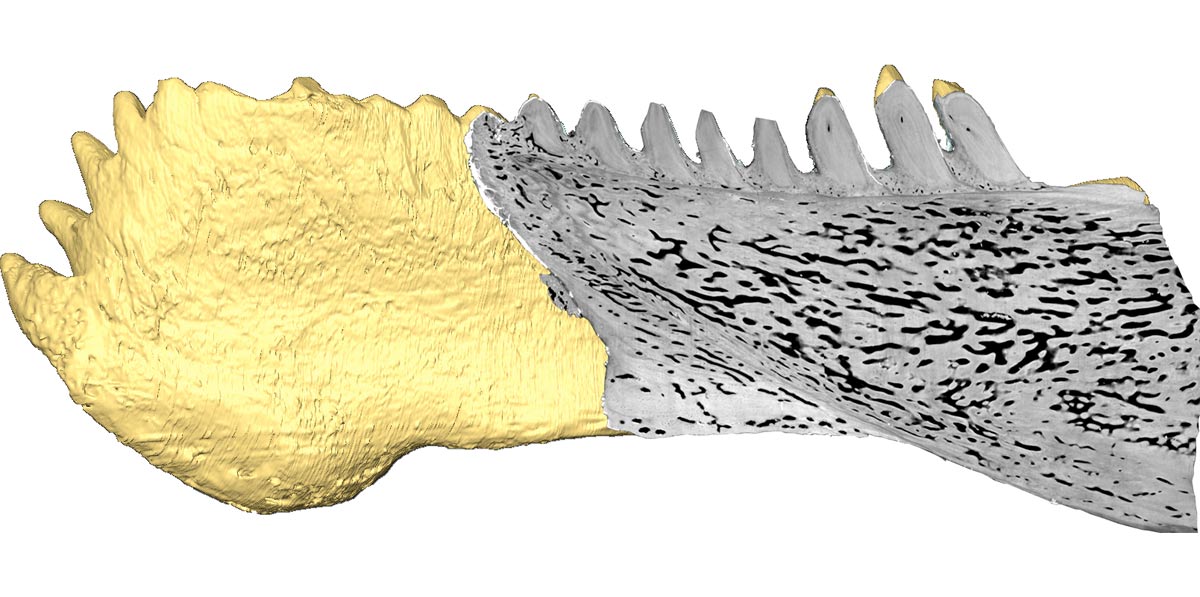

The researchers analyzed specimens from an extinct placoderm, Compagopiscis, using high-energy X-rays from a kind of particle accelerator known as a synchrotron at the Swiss Light Source at the Paul Scherrer Institute in Switzerland. [Image Gallery: Stunning Fish X-Rays]

"The fossils are very rare and so no museum would ever allow anyone to cut them up to study structure," Donoghue said.

Regular CT scanning would not reveal the internal structure of these fossils at a resolution fine enough to look for signs of teeth. "It is only with synchrotron tomography that we can obtain the high resolution we need using a non-destructive method," Donoghue said. This technique involves speeding charged particles through magnetic fields; the resulting release of high-energy light can penetrate opaque materials like bones to produce high-resolution 3D images.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We were able to visualize every tissue, cell and growth line within the bony jaws, allowing us to study the development of the jaws," researcher Martin Rücklin at the University of Bristol said in a statement.

The placoderm teeth had components seen in modern teeth, such as dentin, the hard, dense bony tissue forming the bulk of the tooth beneath the enamel, and a pulp cavity, which creates dentin.

"We show that the juveniles had teeth for processing and capturing prey before they were worn away in the adults," Donoghue said.

This discovery that the earliest jawed vertebrates were toothy suggests teeth evolved along with or soon after jaws did. The scientists detailed their findings online today (Oct. 17) in the journal Nature.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus