Mariana Trench: The deepest depths

The Mariana Trench reaches more than 7 miles below the surface of the Pacific Ocean.

The Mariana Trench is the deepest oceanic trench on Earth and home to the two lowest points on the planet.

The crescent-shaped trench is in the Western Pacific, just east of the Mariana Islands near Guam. The region surrounding the trench is noteworthy for many unique environments, including vents bubbling up liquid sulfur and carbon dioxide, active mud volcanoes and marine life adapted to pressures 1,000 times that at sea level.

The Challenger Deep, in the southern end of the Mariana Trench (sometimes called the Marianas Trench), is the deepest spot in the ocean. Its depth is difficult to measure from the surface, but in 2010, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration used sound pulses sent through the ocean and pegged the Challenger Deep d at 36,070 feet (10,994 meters). A 2021 estimate using pressure sensors found the deepest spot in Challenger Deep was 35,876 feet (10,935 m). Other modern estimates vary by less than 1,000 feet (305 m).

The ocean's second-deepest place is also in the Mariana Trench. The Sirena Deep, which lies 124 miles (200 kilometers) to the east of Challenger Deep, is a crushing 35,462 feet deep (10,809 m).

By comparison, Mount Everest stands at 29,026 feet (8,848 m) above sea level, meaning the deepest part of the Mariana Trench is 7,044 feet (2,147 m) deeper than Everest is tall.

Who owns the Mariana Trench?

The Mariana Trench is 1,580 miles (2,542 km) long — more than five times the length of the Grand Canyon. However, the narrow trench averages only 43 miles (69 km) wide.

Because Guam is a United States territory and the 15 Northern Mariana Islands are governed by a U.S. Commonwealth, the U.S. has jurisdiction over the Mariana Trench. In 2009, former President George W. Bush established the Mariana Trench Marine National Monument, which created a protected marine reserve for the approximately 195,000 square miles (506,000 square km) of seafloor and waters surrounding the remote islands. The monument includes most of the Mariana Trench, 21 underwater volcanoes and areas around three islands.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

How did the Mariana Trench form?

The Mariana Trench was created by the process that occurs in a subduction zone, where two massive slabs of oceanic crust, known as tectonic plates, collide. At a subduction zone, one piece of oceanic crust is pushed and pulled underneath the other, sinking into the Earth's mantle, the layer under the crust. Where the two pieces of crust intersect, a deep trench forms above the bend in the sinking crust. In this case, the Pacific Ocean crust is bending below the Philippine crust.

The Pacific crust is about 180 million years old where it dives into the trench. The Philippine plate is younger and smaller than the Pacific plate.

As deep as the trench is, it is not the spot closest to the center of Earth. Because the planet bulges at the equator, the radius at the poles is about 16 miles (25 km) less than the radius at the equator. So, parts of the Arctic Ocean seabed are closer to the Earth's center than the Challenger Deep.

The crushing water pressure on the floor of the trench is more than 8 tons per square inch (703 kilograms per square meter). This is more than 1,000 times the pressure felt at sea level, or the equivalent of having 50 jumbo jets piled on top of a person.

Are there volcanoes in the Mariana Trench?

A chain of volcanoes that rise above the ocean waves to form the Mariana Islands mirrors the crescent-shaped arc of the Mariana Trench. Interspersed with the islands are many strange undersea volcanoes.

For example, the Eifuku submarine volcano spews liquid carbon dioxide from hydrothermal vents similar to chimneys. The liquid coming out of these chimneys is 217 degrees Fahrenheit (103 degrees Celsius). At the nearby Daikoku submarine volcano, scientists discovered a pool of molten sulfur 1,345 feet (410 m) below the ocean surface, something seen nowhere else on Earth, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

What lives in the Mariana Trench?

Recent scientific expeditions have discovered surprisingly diverse life in these harsh conditions. Animals living in the deepest parts of the Mariana Trench survive in complete darkness and extreme pressure, said Natasha Gallo, a doctoral student at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography who has studied video footage from filmmaker James Cameron's 2012 expedition into the trench.

Food in the Mariana Trench is extremely limited, because the deep gorge is far from land. Terrestrial plant material rarely finds its way into the bottom of the trench, Gallo told Live Science, and dead plankton sinking from the surface must drop thousands of feet to reach Challenger Deep. Instead, some microbes rely on chemicals, such as methane or sulfur, while other creatures gobble marine life that’s below them on the food chain.

The three most common organisms at the bottom of the Mariana Trench are xenophyophores, amphipods and small sea cucumbers (holothurians), Gallo said.

"These are some of the deepest holothurians ever observed, and they were relatively abundant," Gallo said.

The single-celled xenophyophores resemble giant amoebas, and they eat by surrounding and absorbing their food. Amphipods are shiny, shrimplike scavengers commonly found in deep-sea trenches; how they survived down there was a bit of a mystery, because amphipod shells dissolve easily in the high pressures of the Mariana Trench. But in 2019, Japanese researchers found that at least one species of the Mariana Trench dwellers uses aluminum, extracted from seawater, to shore up its shell.

During Cameron's 2012 expedition, scientists also spotted microbial mats in the Sirena Deep, the zone east of the Challenger Deep. These clumps of microbes feed on hydrogen and methane released by chemical reactions between seawater and rocks.

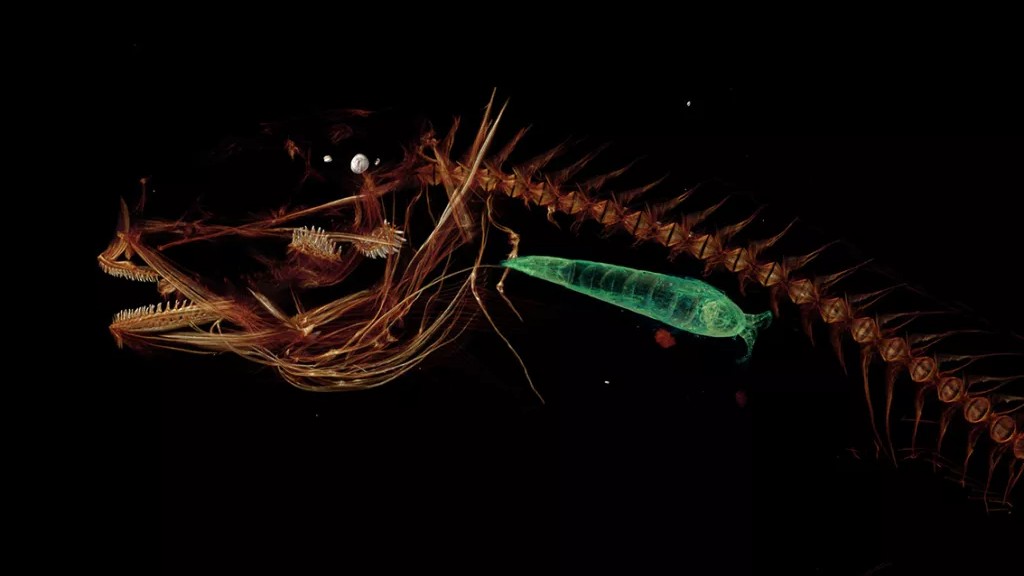

One of the region's top predators is a deceptively vulnerable-looking fish. In 2017, scientists reported they had collected specimens of an unusual creature, dubbed the Mariana snailfish, which lives at a depth of about 26,200 feet (8,000 m). The snailfish's small, pink and scaleless body hardly seems capable of surviving in such a punishing environment, but this fish is full of surprises, researchers reported in a study published that year in the journal Zootaxa. The animal appears to dominate in this ecosystem, going deeper than any other fish and exploiting the absence of competitors by gobbling up the plentiful invertebrate prey that inhabit the trench, the study authors wrote.

Is the Mariana Trench polluted?

Unfortunately, the deep ocean can act as a potential sink for discarded pollutants and litter. In a study published in 2017 in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution, a research team led by scientists at Newcastle University in the United Kingdom showed that human-made chemicals that were banned in the 1970s are still lurking in the deepest parts of the ocean.

While sampling amphipods (shrimp-like crustaceans) from the Mariana and Kermadec trenches, the researchers discovered extremely high levels of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in the organisms’ fatty tissues. These included polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), chemicals commonly used as electrical insulators and flame retardants, according to a study published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution. These POPs were released into the environment through industrial accidents and landfill leakages from the 1930s until the 1970s when they were finally banned.

"We still think of the deep ocean as being this remote and pristine realm, safe from human impact, but our research shows that, sadly, this could not be further from the truth,” lead study author Alan Jamieson, a senior lecturer in Marine Ecology at Newcastle University, said in a statement.

In fact, the amphipods in the study contained levels of contamination similar to that found in Suruga Bay, one of the most polluted industrial zones of the northwest Pacific.

Since POPs cannot degrade naturally, they persist in the environment for decades, reaching the bottom of the ocean by way of contaminated plastic debris and dead animals. The pollutants are then carried from creature to creature through the ocean’s food chain, eventually resulting in chemical concentrations far higher than surface level pollution.

"The fact that we found such extraordinary levels of these pollutants in one of the most remote and inaccessible habitats on Earth really brings home the long term, devastating impact that humankind is having on the planet," Jamieson said in the statement.

Nor is the Mariana Trench immune from the plastic pollution that invades the world's oceans. A 2018 paper in the journal Geochemical Perspectives found that microplastics were alarmingly common in the lowest waters of the Mariana Trench, indicating that these plastics filter through the ocean to concentrate at its deepest points.

Has anyone ever dived into the Mariana Trench?

People have been exploring the Mariana Trench for more than a century.

- In 1875, the trench was discovered by the HMS Challenger using recently-invented sounding equipment during a global circumnavigation, according to the website for DeepSea Challenge, Cameron’s 2012 solo expedition into the trench. In 1951, the trench was sounded again by HMS Challenger II. Challenger Deep, the deepest part of the trench, was named after the two vessels.

- The first crewed vessel to reach the bottom of Challenger Deep was a "deep boat" named Trieste, which made the journey in 1960. Crewed by U.S. Navy Lt. Don Walsh and Swiss scientist Jacques Piccard, the submersible reached a depth of 35,797 feet (10,911 m).

- In 2012, James Cameron became the pilot of the second mission to reach the bottom of the Challenger Deep. The filmmaker solo-piloted the submersible the Deepsea Challenger, filming footage for National Geographic. He dove just shy of the original record, reaching a depth of 35,787 feet (10,908 m).

- In 2019, explorer and businessman Victor Vescovo piloted the DSV Limiting Factor, breaking the record for deepest dive into Challenger Deep. He descended 35,853 feet (10,927 m).

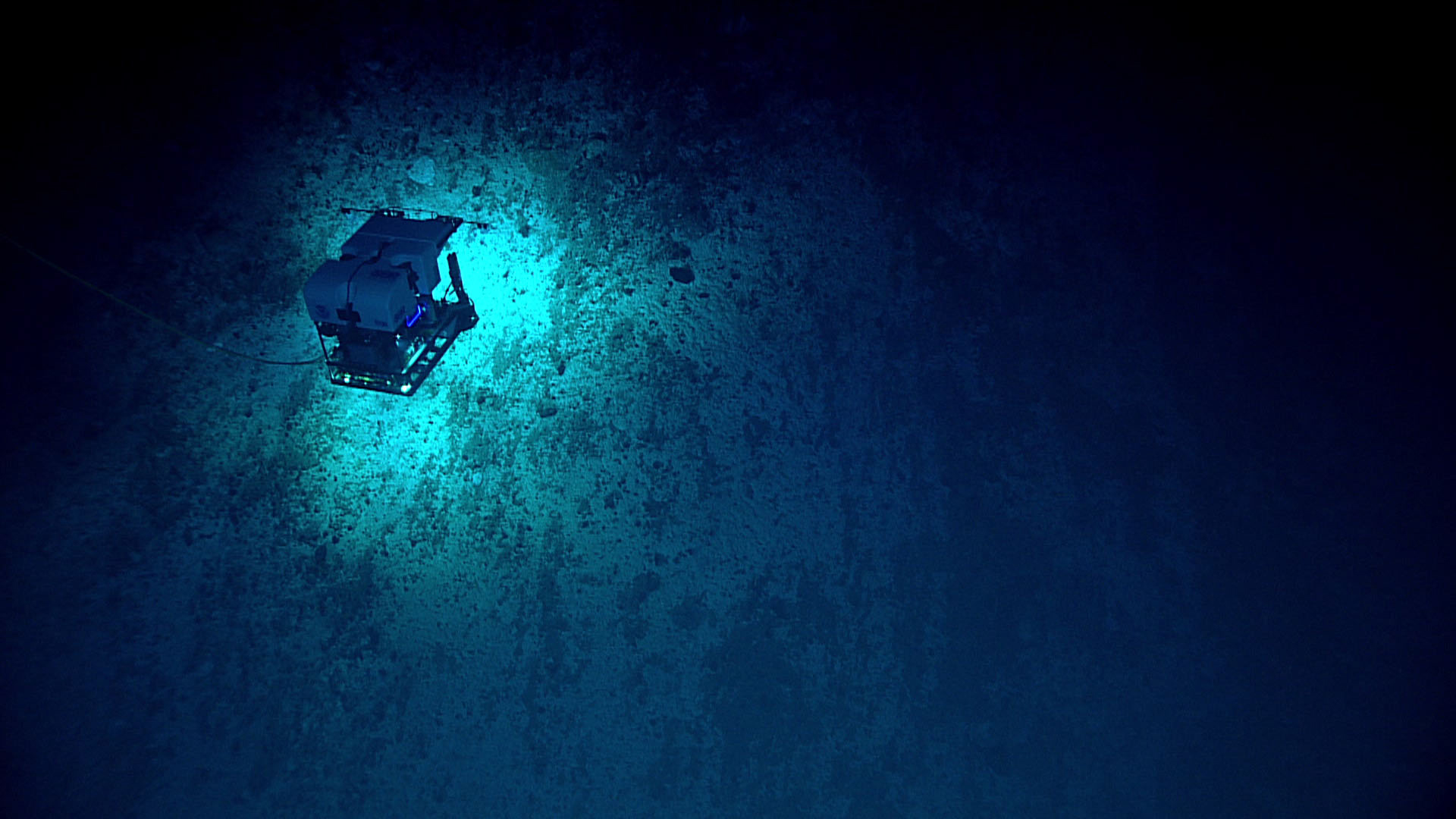

- Uncrewed journeys into the trench by robotic submersibles have also expanded human knowledge of this deep ocean frontier. In 1995, the Japanese uncrewed submarine Kaiko gathered samples and data from the trench. In 2009, the U.S. hybrid remotely operated vehicle Nereus traveled to the floor of Challenger Deep and remained there for 10 hours, recording video. (Nereus would later implode in 2014 while exploring another deep-sea trench, the Kermadec Trench, according to the BBC.)

- In 2021, a Spanish expedition, Caladan Oceanic's Ring of Fire Expedition, Part II, collected mantle rocks from the bottom of the Marianas Trench that contained microbial mats.

This article was updated on May 16, 2022, by Live Science contributor Stephanie Pappas, with additional reporting by Elizabeth Dohrer and Traci Pedersen, Live Science contributors.

Additional resources

- For more on how to measure the depth of the deepest place on Earth, see So, How Deep Is the Mariana Trench? (PDF), a paper in the journal Marine Geodesy that discusses the methods and variations between estimates.

- The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service manages the Mariana Trench Marine National Monument, and their webpage contains the latest news on conservation and discovery in the monument.

- Finally, NASA maps of the trench reveal the graceful crescent swoop of the landform.

Bibliography

Amos, J. (2014, May 12). Nereus deep sea sub 'implodes' 10km-down. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-27374326. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

Carolwicz, M. (2012, April 14). New View of the Deepest Trench. NASA Earth Observatory. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/77640/new-view-of-the-deepest-trench. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

Embley, B. (2006, May 4). Discovery of the Sulfur Cauldron at Daikoku Volcano: A Window into an Active Volcano. NOAA Ocean Explorer. https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/06fire/logs/may4/may4.html.

Gardner, J. V., Armstrong, A. A., Calder, B. R., & Beaudoin, J. (2014). So, how deep is the mariana trench? Marine Geodesy, 37(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490419.2013.837849

Greenaway, S. F., Sullivan, K. D., Umfress, S. H., Beittel, A. B., & Wagner, K. D. (2021). Revised depth of the Challenger Deep from submersible transects; including a general method for precise, pressure-derived depths in the Ocean. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 178, 103644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2021.103644

Jamieson, A. J., Malkocs, T., Piertney, S. B., Fujii, T., & Zhang, Z. (2017). Bioaccumulation of persistent organic pollutants in the deepest ocean fauna. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 1(3). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-016-0051

Jamieson, A.J. (2017, February 14). Comment: How we discovered pollution-poisoned crustaceans. Newcastle University Press Office. https://www.ncl.ac.uk/press/articles/archive/2017/02/marianatrenchpollution/

Mariana Trench: Challenger Deep and Sirena Deep dives. https://caladanoceanic.com/expeditions/mariana/. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

Marianas Trench Marine National Monument. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. https://www.fws.gov/national-monument/marianas-trench-marine. Retrieved May 10, 2022.

Peng, X., Chen, M., Chen, S., Dasgupta, S., Xu, H., Ta, K., Du, M., Li, J., Guo, Z., & Bai, S. (2018). Microplastics contaminate the deepest part of the world’s Ocean. Geochemical Perspectives Letters, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.7185/geochemlet.1829

The Mariana Trench. http://www.deepseachallenge.com/the-expedition/mariana-trench/ Retrieved May 10, 2022.

- Stephanie PappasLive Science Contributor

- Traci PedersenLive Science Contributor

- Elizabeth DohrerLive Science Contributor