Science and the scientific method: Definitions and examples

Here's a look at the foundation of doing science — the scientific method.

Science is a systematic and logical approach to discovering how things in the universe work. It is also the body of knowledge accumulated through the discoveries about all the things in the universe.

The word "science" is derived from the Latin word "scientia," which means knowledge based on demonstrable and reproducible data, according to the Merriam-Webster dictionary. True to this definition, science aims for measurable results through testing and analysis, a process known as the scientific method. Science is based on fact, not opinion or preferences. The process of science is designed to challenge ideas through research. One important aspect of the scientific process is that it focuses only on the natural world, according to the University of California, Berkeley. Anything that is considered supernatural, or beyond physical reality, does not fit into the definition of science.

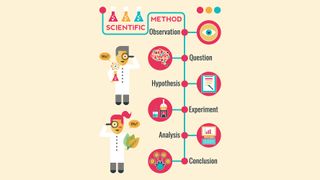

The scientific method

When conducting research, scientists use the scientific method to collect measurable, empirical evidence in an experiment related to a hypothesis (often in the form of an if/then statement) that is designed to support or contradict a scientific theory.

"As a field biologist, my favorite part of the scientific method is being in the field collecting the data," Jaime Tanner, a professor of biology at Marlboro College, told Live Science. "But what really makes that fun is knowing that you are trying to answer an interesting question. So the first step in identifying questions and generating possible answers (hypotheses) is also very important and is a creative process. Then once you collect the data you analyze it to see if your hypothesis is supported or not."

The steps of the scientific method go something like this, according to Highline College:

- Make an observation or observations.

- Form a hypothesis — a tentative description of what's been observed, and make predictions based on that hypothesis.

- Test the hypothesis and predictions in an experiment that can be reproduced.

- Analyze the data and draw conclusions; accept or reject the hypothesis or modify the hypothesis if necessary.

- Reproduce the experiment until there are no discrepancies between observations and theory. "Replication of methods and results is my favorite step in the scientific method," Moshe Pritsker, a former post-doctoral researcher at Harvard Medical School and CEO of JoVE, told Live Science. "The reproducibility of published experiments is the foundation of science. No reproducibility — no science."

Some key underpinnings to the scientific method:

- The hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable, according to North Carolina State University. Falsifiable means that there must be a possible negative answer to the hypothesis.

- Research must involve deductive reasoning and inductive reasoning. Deductive reasoning is the process of using true premises to reach a logical true conclusion while inductive reasoning uses observations to infer an explanation for those observations.

- An experiment should include a dependent variable (which does not change) and an independent variable (which does change), according to the University of California, Santa Barbara.

- An experiment should include an experimental group and a control group. The control group is what the experimental group is compared against, according to Britannica.

Hypothesis, theory and law

The process of generating and testing a hypothesis forms the backbone of the scientific method. When an idea has been confirmed over many experiments, it can be called a scientific theory. While a theory provides an explanation for a phenomenon, a scientific law provides a description of a phenomenon, according to The University of Waikato. One example would be the law of conservation of energy, which is the first law of thermodynamics that says that energy can neither be created nor destroyed.

A law describes an observed phenomenon, but it doesn't explain why the phenomenon exists or what causes it. "In science, laws are a starting place," said Peter Coppinger, an associate professor of biology and biomedical engineering at the Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. "From there, scientists can then ask the questions, 'Why and how?'"

Laws are generally considered to be without exception, though some laws have been modified over time after further testing found discrepancies. For instance, Newton's laws of motion describe everything we've observed in the macroscopic world, but they break down at the subatomic level.

This does not mean theories are not meaningful. For a hypothesis to become a theory, scientists must conduct rigorous testing, typically across multiple disciplines by separate groups of scientists. Saying something is "just a theory" confuses the scientific definition of "theory" with the layperson's definition. To most people a theory is a hunch. In science, a theory is the framework for observations and facts, Tanner told Live Science.

A brief history of science

The earliest evidence of science can be found as far back as records exist. Early tablets contain numerals and information about the solar system, which were derived by using careful observation, prediction and testing of those predictions. Science became decidedly more "scientific" over time, however.

1200s: Robert Grosseteste developed the framework for the proper methods of modern scientific experimentation, according to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. His works included the principle that an inquiry must be based on measurable evidence that is confirmed through testing.

1400s: Leonardo da Vinci began his notebooks in pursuit of evidence that the human body is microcosmic. The artist, scientist and mathematician also gathered information about optics and hydrodynamics.

1500s: Nicolaus Copernicus advanced the understanding of the solar system with his discovery of heliocentrism. This is a model in which Earth and the other planets revolve around the sun, which is the center of the solar system.

1600s: Johannes Kepler built upon those observations with his laws of planetary motion. Galileo Galilei improved on a new invention, the telescope, and used it to study the sun and planets. The 1600s also saw advancements in the study of physics as Isaac Newton developed his laws of motion.

1700s: Benjamin Franklin discovered that lightning is electrical. He also contributed to the study of oceanography and meteorology. The understanding of chemistry also evolved during this century as Antoine Lavoisier, dubbed the father of modern chemistry, developed the law of conservation of mass.

1800s: Milestones included Alessandro Volta's discoveries regarding electrochemical series, which led to the invention of the battery. John Dalton also introduced atomic theory, which stated that all matter is composed of atoms that combine to form molecules. The basis of modern study of genetics advanced as Gregor Mendel unveiled his laws of inheritance. Later in the century, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen discovered X-rays, while George Ohm's law provided the basis for understanding how to harness electrical charges.

1900s: The discoveries of Albert Einstein, who is best known for his theory of relativity, dominated the beginning of the 20th century. Einstein's theory of relativity is actually two separate theories. His special theory of relativity, which he outlined in a 1905 paper, "The Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies," concluded that time must change according to the speed of a moving object relative to the frame of reference of an observer. His second theory of general relativity, which he published as "The Foundation of the General Theory of Relativity," advanced the idea that matter causes space to curve.

In 1952, Jonas Salk developed the polio vaccine, which reduced the incidence of polio in the United States by nearly 90%, according to Britannica. The following year, James D. Watson and Francis Crick discovered the structure of DNA, which is a double helix formed by base pairs attached to a sugar-phosphate backbone, according to the National Human Genome Research Institute.

2000s: The 21st century saw the first draft of the human genome completed, leading to a greater understanding of DNA. This advanced the study of genetics, its role in human biology and its use as a predictor of diseases and other disorders, according to the National Human Genome Research Institute.

Additional resources

- This video from City University of New York delves into the basics of what defines science.

- Learn about what makes science science in this book excerpt from Washington State University.

- This resource from the University of Michigan — Flint explains how to design your own scientific study.

Bibliography

Merriam-Webster Dictionary, Scientia. 2022. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/scientia

University of California, Berkeley, "Understanding Science: An Overview." 2022. https://undsci.berkeley.edu/article/0_0_0/intro_01

Highline College, "Scientific method." July 12, 2015. https://people.highline.edu/iglozman/classes/astronotes/scimeth.htm

North Carolina State University, "Science Scripts." https://projects.ncsu.edu/project/bio183de/Black/science/science_scripts.html

University of California, Santa Barbara. "What is an Independent variable?" October 31,2017. http://scienceline.ucsb.edu/getkey.php?key=6045

Encyclopedia Britannica, "Control group." May 14, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/science/control-group

The University of Waikato, "Scientific Hypothesis, Theories and Laws." https://sci.waikato.ac.nz/evolution/Theories.shtml

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Robert Grosseteste. May 3, 2019. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/grosseteste/

Encyclopedia Britannica, "Jonas Salk." October 21, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jonas-Salk

National Human Genome Research Institute, "Phosphate Backbone." https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Phosphate-Backbone

National Human Genome Research Institute, "What is the Human Genome Project?" https://www.genome.gov/human-genome-project/What

Live Science contributor Ashley Hamer updated this article on Jan. 16, 2022.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.