Treatable STD Scarier Than Fatal Flu, Study Finds

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Passing someone a sexually transmitted infection is viewed as worse than giving them the flu — even if the flu turns out to be fatal, a new study finds.

The research points to an "irrational" stigma of sexually transmitted diseases, according to study researcher Amy Moors, a graduate student in psychology at the University of Michigan. Infections such as the flu, no matter how deadly, simply don't garner the same disgust.

"It turns out that people really fear chlamydia," the STI focused on in the study, Moor told LiveScience. "They rate a person who transmits chlamydia as very risky, very selfish, immoral, dirty, bad, any adjective you can think of that is terrible."

STI stigma

The stigma surrounding STIs can keep people from getting tested, discussing testing with partners or disclosing to partners that they do have an infection, Moor said. She and her colleagues wanted to understand how much stigma really influences people's perceptions of these diseases.

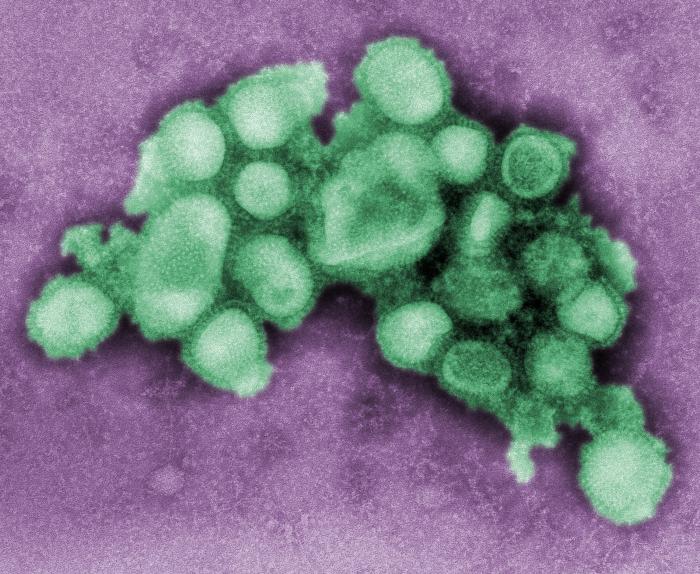

To do so, the researchers gathered 1,158 volunteers via the Internet and had each read a short paragraph about someone transmitting either the H1N1 flu, also called swine flu, or chlamydia to another person. Though H1N1 usually causes nothing more than a few days of misery, people with compromised immune systems, the elderly and the very young can die of it.

Chlamydia, on the other hand, is a bacterial infection and one of the most frequently reported STIs. There are often few symptoms, but the infection can cause infertility in women if left untreated. [Top 10 Stigmatized Health Disorders]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In every scenario in the study, "Christina" or "James" feels a little ill, but shrugs off the symptoms, goes to a party and has sex with a fellow partygoer. In some cases, this sexual encounter transmits chlamydia to their partner. In other cases, it transmits H1N1.

In the chlamydia scenarios, the newly infected person had to go to the doctor and take a week's worth of medications to clear up the infection. The same was true for some flu victims, but since H1N1 can be deadly, Moor and her colleagues added two other unhappy endings to some of the stories: In one, the person had to go to the hospital and "nearly died" of the flu. In another, the flu actually killed the person.

After reading one of these scenarios, each participant answered a series of questions about how selfish, risky and all-around irresponsible they would rate either Christina or James.

Who's afraid of the big, bad Chlamydia?

Keeping a sexual mode of transmission constant was meant to control for any automatic "sex is taboo" reactions from participants, Moor said. But despite the fact that the characters James and Christina acted sexually identically in all scenarios, chlamydia seemed to strike extra fear into participants' hearts.

When Christina or James were said to have transmitted chlamydia, people judged them harshly, ranking them as almost as selfish and risky as was possible in the survey. When H1N1 was the disease in question, however, people rated the transmitter much more generously. Even when the sexual partner actually died of H1N1, transmitting chlamydia was seen as much more risky and irresponsible than transmitting the flu.

"It's quite confusing," Moor said. "If sex is taboo and that's why people are thinking STIs are so stigmatized, we just nipped that in the bud. We're showing that you can get H1N1 through sex, but it's still not stigmatized."

Moor presented the research in January at the annual meeting of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology in San Diego. Her doctoral advisor at the University of Michigan is Terri Conley.

It's possible that even when told H1N1 has been transmitted through sex, people still link chlamydia more closely with sexual behavior, Moor said. Next, she and her colleagues plan to take sex out of the equation entirely. They'll place a Petri dish labeled either "H1N1" or "chlamydia" in a room and ask study participants to wait in that room for a researcher to come start a psychology experiment. Unbeknownst to the participants, the waiting will be the experiment, Moor said.

"We're going to see how far away they walk from it or how long they stare at it or if disgust comes on their face," Moor said. "So we're going to video record the whole time they're next to a Petri dish to take sex completely out of the equation."

The goal, Moor said, is to figure out exactly what it is about STIs, if not disease outcome or moral judgments about sex, that cause irrational stigma. It's considered perfectly acceptable to admit you have the flu and to get medical help right away, Moor said, but denial and fear surround STI testing and treatment.

"If the stigma were reduced, then maybe there would be more preventative care," she said.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus