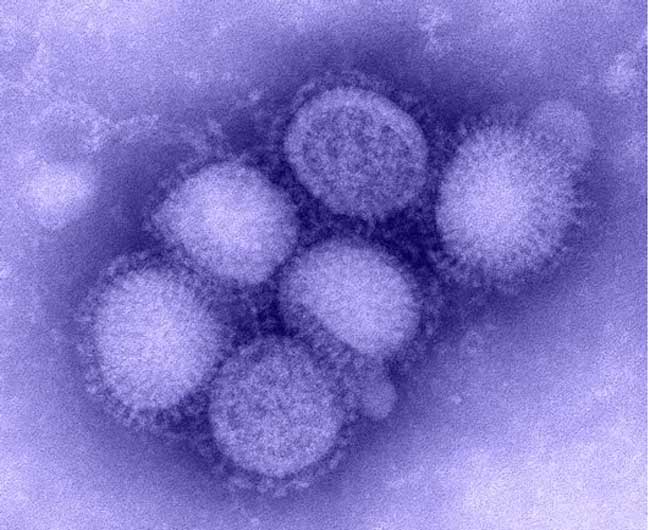

Innards of H1N1 Virus Resemble 'Flu Sausage'

On March 28, one month before news of the swine flu outbreak headlined worldwide, a nine-year-old girl in Imperial County, California, ran a fever of 104.3°F. She had not rolled up her sleeve for this year’s flu vaccine, but that day she opened her mouth and stuck out her tongue for a cotton swab that scooped up mucous samples from her throat. Her mucus arrived at the Naval Health Research Center in San Diego where technicians tested it and classified the virus in it as “unsubtypable” influenza A – it was something new. She recovered. The lab forwarded her mucus to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, where it arrived on April 17, four days after Mexico confirmed its first case of swine flu. Embedded in the girl’s mucus was a strain of the virus that was already sweeping the globe. To date, 41 countries have confirmed more than 11,000 swine flu cases, a global contagion that has proved less deadly than scientists feared at its onset. The CDC discovered the virus is a mashed-up concoction of human, avian and pig flu genes – a kind of flu sausage. Some of it is from viruses that are common in North America, native to pigs that have coughed it onto each other since 1999. But some of the gene combinations have never been seen before in pigs or people. For years scientists have speculated on the potential for a deadly hybrid virus to form in pigs. Now, the biggest swine flu outbreak in history may be the first evidence that this can happen. Over the last ten years, new flu strains have been cropping up in pigs on farms and scientists don’t know why. However, they had predicted it years before it began. “I have warned that there could be viruses originating in swine jumping to humans and creating pandemics,” says Juergen Richt, a veterinary virologist at Kansas State University. Richt and his colleagues drew together a frightening array of studies of flu viruses extracted from people and a small zoo of animals over the past several decades. They revealed their findings in January in a prescient paper called “The Pig as a Mixing Vessel for Influenza Viruses,” published in the Journal of Molecular and Genetic Medicine. Pigs are flu sponges, capable of contracting both bird and human viruses that can jump across the species barrier, Richt says. The 1957 and 1968 Asian flu pandemics were caused by mixed-and-matched, reassorted viruses. Richt contends that the viruses jumped from birds to people and transformed inside their new hosts, or that they jumped from birds to a mammal, such as pigs, where they shuffled their genes and formed new flu viruses. Pigs and people can swap mutations of the virus among themselves in a risky game of viral hot potato. For years the 1918 flu pandemic that claimed 20 to 40 million people worldwide was blamed on pigs. Then researchers conducted some clever genetic archeology that cast doubt on the swine flu theory. Scientists now suspect that birds infected us, and we, in turn, infected the pigs. Pigs have infected people with mixed-up viruses before, even triple whammies made of pig, bird and human flu genes, Richt’s paper shows. If the innards of each pig are Petri dishes where genes are jumbled and dashed together, then possible pandemic flu viruses have been stewing on hog farms for decades. “Everyone was looking at avian flu in southeast China and we said, ‘You guys forget it could happen in your own backyard,’” Richt said. Not every flu virus can infect every animal. Birds, for example don’t have receptors for human strains of the flu. Two different strains can only mix inside a body that has receptors for both. Pigs are one such host for a flu virus — they can get sick with both avian and human strains. To reproduce, the flu virus slips inside its host’s cells and makes copies of itself, explains Gene Erickson, a microbiologist at Rollins Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory in North Carolina. The virus’ genome has eight segments, each of which it copies and assembles into new viruses. When two viruses invade the same cell, they both begin to copy themselves. At that point there are not just eight, but 16 viral segments on assembly lines, and the genes start shuffling together in a process called reassortment. In that way, “mixing is possible, resulting in a new type of virus, like the virus that is currently infecting people,” Erickson said. If there are three different viruses in the cell, even more combinations are possible. Until now, swine flu has been easy to ignore. Pigs don’t easily infect people, and when they do, the virus often fizzles in its new host, unable to infect other people. Once inside a person the infection from the pig hits a dead end. According to a comprehensive study published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, swine flu had infected only several dozen people in the world since it was first identified in 1930. As of 2006 only 50 cases were reported worldwide. Adding 12 cases that the CDC has documented since then (before the current outbreak) makes the total 62. Then, in the last ten years something changed. Ever since the late 1990s, flu viruses have been reassembling themselves inside pigs at a heightened pace. Pigs began coughing new viruses into the air. “The change we’ve seen is a different kind of change. In fact we’ve seen the creation of a new kind of virus through the process of reassortment,” said Christopher Olsen, a public health professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and co-author of the study. “The viruses we’ve seen emerge in pigs are a mixture of the classical swine flu, avian flu and human flu,” he said. Experts also witnessed the emergence of a new subtype in 1998. “We’ve not been able to determine any specific reasons for why that began to happen,” Olsen said. At the onset of the current outbreak Olsen was concerned. “This virus is substantially different from what we’ve seen in the past and it has the potential to spread from person to person,” he said. For now, the virus’ apparently low death toll has assuaged some fears. This outbreak is a mostly scientific curiosity of mixed up genes—one that was quietly predicted in early warnings from the scientific community. This story is provided by Scienceline, a project of New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.

- Is Swine Flu Pandemic Imminent?

- 5 Essential Swine Flu Survival Tips

- Q&A: Swine Flu Myths and Mysteries

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.