Sumerian Beer May Have Been Alcohol-Free

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The fermented cereal beverage enjoyed by Sumerians, so-called Sumerian beer, may have been alcohol-free, suggests a recent review of ancient Sumerian practices.

While ancient writings and vessel remnants show that Mesopotamia's inhabitants were fond of fermented cereal juice, how the brew was actually made is still a mystery.

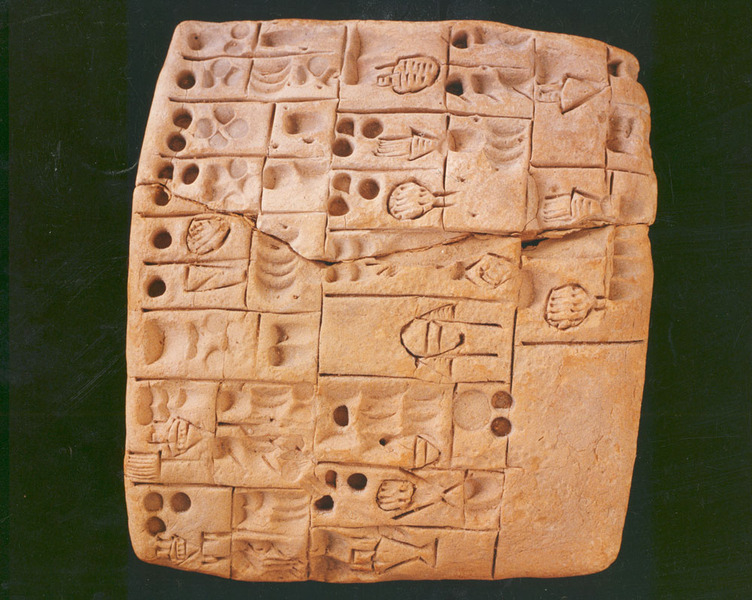

To investigate the brewing technologies of Mesopotamia, the late Peter Damerow, a historian of science and cuneiform-writing scholar at the Max Planck Institute in Germany, reviewed archaeological finds of ancient beer production and consumption, as well as 4000-year-old cuneiform writings, which included Sumerian administrative documents and literary texts dealing with myths and legislation.

Despite being able to pull information from various sources, Damerow concluded that the remnants of Mesopotamia held little clue to the brewing techniques of the Sumerians, and expressed doubts that the popular beverage could be considered beer.

"Given our limited knowledge about the Sumerian brewing processes, we cannot say for sure whether their end product even contained alcohol," Damerow wrote in his study, first published in November in the Cuneiform Digital Library Journal.

Looking over the cuneiform texts, Damerow found that many contained records of brewery deliveries of emmer wheat, barley and malt, but hardly a scrap of information on the beer production processes. While seemingly surprising, the lack of a beer recipe makes sense, as the administrative documents were likely written for an audience already familiar with the details of brewing, according to Damerow.

Whatever information Damerow could glean from the documents was clouded by the fact that the methods used for recording the information differed between locations and time periods. Moreover, the Sumerian bureaucrats didn't base their records and calculations on any consistent number system.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Analyzing the folklore of the time didn't prove any more fruitful. Even the "Hymn of Ninkasi," a mythological poem or song that glorifies the brewing of beer, didn't conclusively describe the process of beer brewing, Damerow stated.

Damerow also reviewed research from 2006 that set out to reconstruct the ancient brewing processes. In the study, archaeologists combined their interpretation of archaeological finds at Tall Bazi, a 13th-century settlement located in northern Syria, about 37 miles south of the Turkish border, with their own brewing experiments using local ingredients and brewing devices. While the scientists were able to produce a brew of barley and emmer, Damerow stressed that the experiment only demonstrates how modern methods can produce a beer under the same conditions that were prevalent in Tall Bazi, which may not be representative of other areas in Mesopotamia.

Such an approach, however, could help work out the mysteries behind the Sumerian art of brewing. "Such interdisciplinary research efforts might well lead to better interpretations of the 'Hymn of Ninkasi' than those currently accepted among specialists working on cuneiform literature," Damerow wrote in the journal article.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus