Life's Extremes: Democrat vs. Republican

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The presidential race is really heating up, and some voters are already casting their ballots for Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton or Republican Donald Trump. Given the United States' starkly divided political climate, one might think it obvious that fundamental, built-in differences exist between Democrats and Republicans.

Science has suggested that there are key features in the brains of liberals and conservatives — bywords, respectively, for Democrats and Republicans these days — that might help explain why people think and vote the way they do.

"There are converging lines of evidence for brain regions that make sense as biological correlates for political attitudes," said Darren Schreiber, a professor of political science at the University of California, San Diego.

Related:

- Election Day 2016: A Guide to When, What, Why and How

- Democratic Party Platform 2016: We Fact-Checked the Science

- Republican Party Platform 2016: We Fact-Checked the Science

Yet ideology stems from more than a slightly oversized or under-functioning brain region, researchers say. One's upbringing and experiences matter a great deal in forming political identities, which after all can change over a lifetime, or even a single election season. [People Become More Liberal With Age]

But some individuals do become quite fixed in their political opinions. Such partisanship might speak to an underlying biological bent to worldviews that events and experience cannot undo.

"Generally people who tend to be moderate can go from one side to another, but I don't know of any extreme left-winger that became a right-winger," said Marco Iacoboni, professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral science at the University of California Los Angeles.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ideology, by the numbers

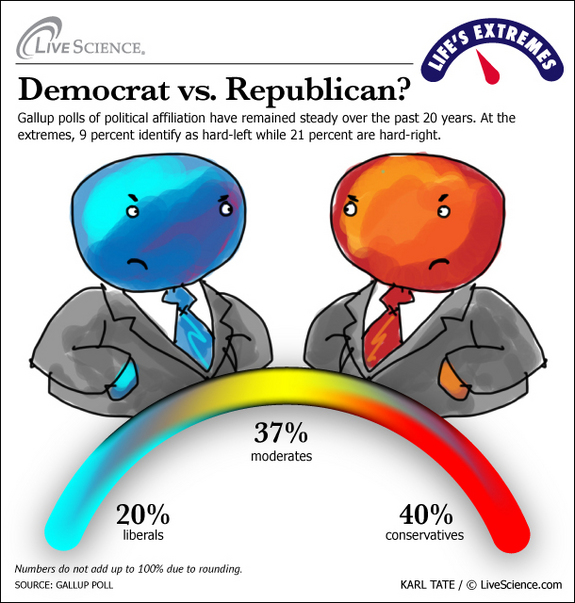

In terms of the percentage of the United States' population that identifies itself as liberal, moderate or conservative, the numbers have held relatively steady over the last 20 years, according to Gallup.

Liberals have remained in the vicinity of 20 percent, moderates, around 37 percent and conservatives a shade higher around 40 percent, since the early 1990s.

At the extremes, those who identify themselves nowadays as hard-left Democrats stands at 9 percent compared with 21 percent who are hard-right Republicans.

A blue or red brain?

Researchers have long wondered if some people can't help but be an extreme left-winger or right-winger, based on innate biology. To an extent, studies of the brains of self-identified liberals and conservatives have yielded some consistent trends, Schreiber said.

Two of these trends are that liberals tend to have more activity in parts of the brain known as the insula and anterior cingulate cortex. Among other functions, the two regions overlap to an extent by dealing with cognitive conflict, in the insula's case, while the anterior cingulate cortex helps in processing conflicting information. [When did Democrats and Republicans switch platforms?]

Conservatives, on the other hand, have demonstrated more activity in the amygdala, known as the brain's "fear center." "If you see a snake or a picture of a snake, the amygdala will light up — it's a threat detector," said Iacoboni.

A study of British subjects published in 2011 supported these past imaging studies with measurements of brain structure. The study showed that on average the amygdala is bigger in conservatives, likely indicating greater use of it in neurological processing. In contrast, liberals often possessed larger anterior cingulate cortexes.

Altogether, these findings suggest liberals can more easily tolerate uncertainty, which might be reflected in their shades-of-gray policy positions. In the U.S., those typically include being pro-choice and lenient on illegal immigration.

Conservatives, meanwhile, have a more binary view of threats versus non-threats. Again, such a predisposition could be extended to policy positions, such as being pro-life and stricter on the immigration issue.

Schreiber cautioned, however, that reinforcement of political views might induce the observed phenomena in the brain, rather than the other way around.

Regardless, it is too simple, he said, to chalk up our political ideologies to brain form and function. "The idea that we're somehow hardwired," Schreiber said, in regards to our political ideologies, "is totally inadequate."

Political dynasties

Indeed, genetic and environment studies have suggested that political attitudes are forged more through experience than some innate tendency.

Research in different countries has dovetailed in showing that at most around 40 percent of political ideology is heritable, meaning mom and dad handed it down through their genes, said Schreiber.

While 40 percent is quite significant, it still means that more than half of one's ideological influences come from life as it is lived, and not in the manner of "programmed" traits, such as height or eye color.

Political identify, Schreiber said, is "really clearly not a story of genes or environment but their interaction."

Politicos, since in utero

All these findings suggest that, to a great extent, humans are very much political creatures. Comparative studies with primates, our closest animal relatives, have shown that a driving evolutionary force behind our large brains has been socialization.

Most primates live in big social groups, wherein alliances form and break, often based on sophisticated forms of behavior, including altruism and deceit.

"Evidence really suggests the reason why we have the brain we do as human beings is to solve this problem of politics," Schreiber told LiveScience. "As we have increasingly complex social organization, we need more and more brain mass to deal with its shifting coalitions."

These coalitions include the big political parties themselves. Voters' loyalty to the Dems or the GOP — or neither — is fickle and can change very fast.

In 2015, 29 percent of the U.S. population called themselves Democrats, 26 percent indicated they were Republicans and 42 percent said they were Independents, according to a Gallup survey.

The ebbs and flows make sense, especially over long periods as political parties' positions and the popularity of their prominent members wax and wane. "Politics is constantly changing," said Schreiber.

In other words, the art (and science) of politicking is far from mastered.

Editor's Note: This article was first published in 2011.

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus