Two Elements Named: Livermorium and Flerovium

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

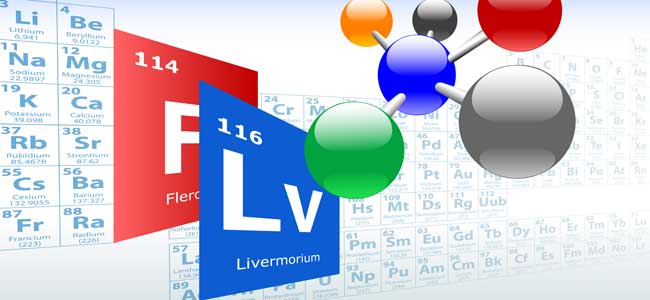

Chemistry's periodic table can now welcome livermorium and flerovium, two newly named elements, which were announced Thursday (Dec. 1) by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. The new names will undergo a five-month public comment period before the official paperwork gets processed and they show up on the table.

Three other new elements just recently finished this process, filling in the 110, 111 and 112 spots.

All five of these elements are so large and unstable they can be made only in the lab, and they fall apart into other elements very quickly. Not much is known about these elements, since they aren't stable enough to do experiments on and are not found in nature. They are called "super heavy," or Transuranium, elements.

The newly named elements fit in the 114 and 116 spots, down in the lower-right corner of the periodic table, and were officially accepted to the periodic table back in June. They originally were synthesized more than 10 years ago, after which repeat experiments led to their confirmation.

Elements 113, 115, 117 and 118 have also been synthesized at Russia's Joint Institute for Nuclear Research, located in Dubna, Russia (about two hours drive from Moscow), but their creation hasn't been confirmed by the International Union yet. Once they have been confirmed, they will also have to go through the naming and public-commenting periods.

Both livermorium and flerovium were also synthesized at the same Russian lab, where Russian researchers were working with American researchers from the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California.

Element 114, previously known as ununquadium, has been named flerovium (Fl), after the Russian institute's Flerov Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions founder, which similarly is named in honor of Georgiy Flerov (1913-1990), a Russian physicist. Flerov's work and his writings to Joseph Stalin led to the development of the USSR's atomic bomb project.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers got their first glimpse at flerovium after firing calcium ions at a plutonium target.

Element 116, which was temporarily named ununhexium, almost ended up with the name moscovium in honor of the region (called an oblast, similar to a province or state) of Moscow, where the research labs are located. In the end, it seems the American researchers won out and the team settled on the name livermorium (Lv), after the national labs and the city of Livermore in which they are located. Livermorium was first observed in 2000, when the scientists created it by mashing together calcium and curium.

"Proposing these names for the elements honors not only the individual contributions of scientists from these laboratories to the fields of nuclear science, heavy-element research, and super-heavy-element research, but also the phenomenal cooperation and collaboration that has occurred between scientists at these two locations," Bill Goldstein, associate director of Lawrence Livermore National Labs' Physical and Life Sciences Directorate, said in a statement.

The names for the next batch of super-heavy atoms is still up for grabs, perhaps moscovium will make a comeback.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus