True Colors of Ancient Beetles Revealed

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

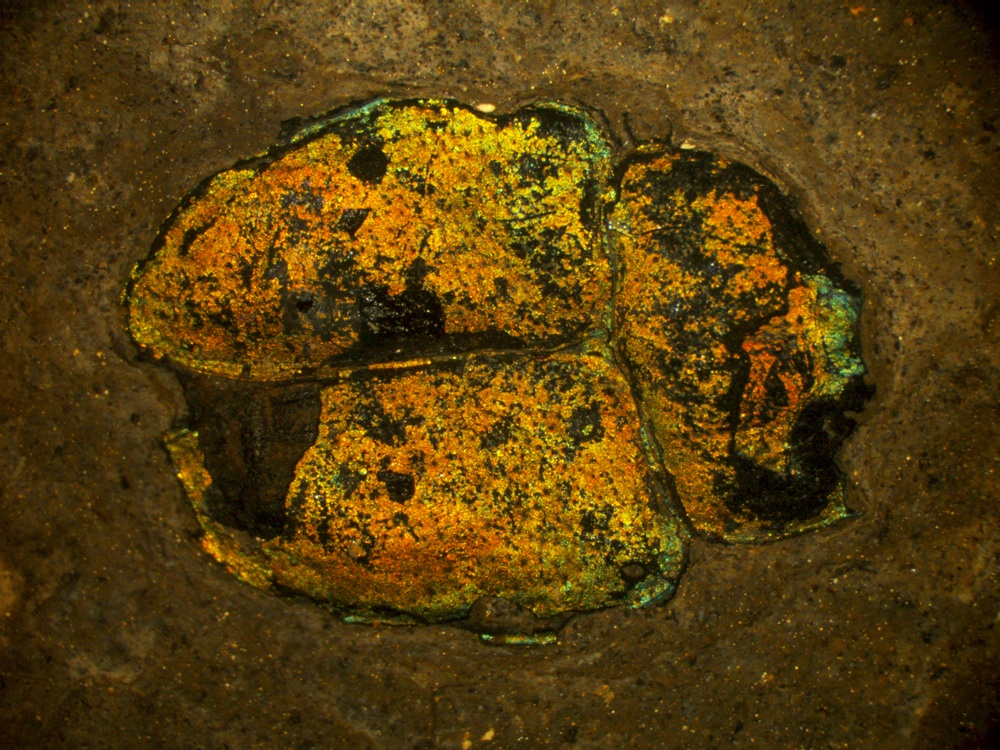

Even after being locked in rock for millions of years, some ancient beetle fossils retain a metallic rainbow sheen. But a new study finds that these bugs undergo changes during fossilization that makes them look slightly redder than they did in life.

Beetles flash some of the most intense colors in nature. The intensity is due to layers of light-scattering materials on the insects' exoskeletons. Many fossils of beetles retain these color-creating structures, but studies on whether the fossils preserve the original colors truthfully have been inconclusive. [See images of the metallic fossilized beetles]

To reveal the insects' true colors, Yale University postdoctoral researcher Maria McNamara and her colleagues took tiny samples from beetle fossils dating back 15 million to 47 million years that were found in various spots in Germany and Idaho. The researchers analyzed the samples using a scanning electron microscope and a transmission electron microscope, both tools that use beams of electrons to create higher-resolution images of an object than could be produced using a light microscope.

The analysis revealed that the structures in the beetle exoskeletons remained virtually unchanged after fossilization, but there was a subtle shift in the way that light traveled through those structures. It seems that the biochemistry of the insects changes during fossilization, the researchers reported today (Sept. 27) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, slightly lengthening the wavelengths of the light refracted by the beetle's armor.

Longer wavelengths of light appear redder, so the fossilized bugs are slightly redder than they were before preservation.

The finding allowed the researchers to correct for this red shift, revealing the original colors of the prehistoric beetles. Understanding the shift will also help researchers predict the presence and original color of ancient insects ranging from dragonflies to butterflies.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus