Buzz Killer: Special Smells Keep Mosquitoes at Bay

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

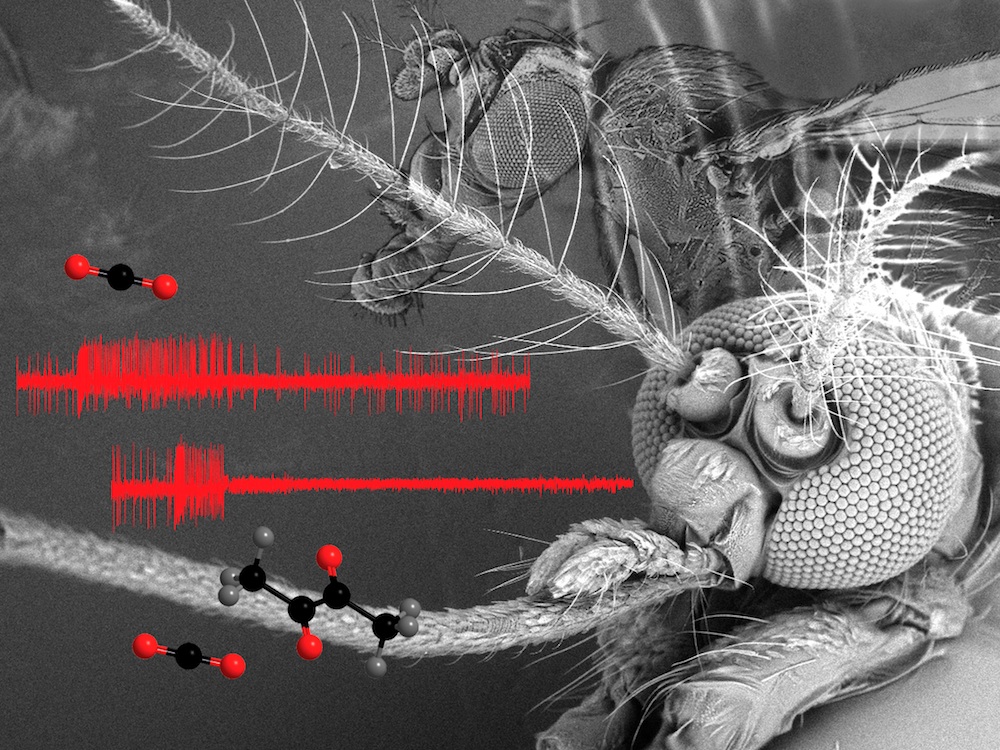

A whiff of one of three newly identified scents can send a mosquito into a bout of woozy bewilderment, scientists find. These odor molecules, they say, may stop the pests from biting and transmitting malaria and other diseases to humans.

'These chemicals offer powerful advantages as potential tools for reducing mosquito-human contact, and can lead to the development of new generations of insect repellents and lures," study researcher Anandasankar Ray, of the University of California, Riverside, said in a statement.

The compounds could help replace the expensive and toxic repellent DEET and help fight malaria and other diseases spread by mosquitoes, which cause millions of deaths per year. [7 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

I want to sense your blood

Female mosquitoes find their blood meal using special structures near their mouths called maxillary palps, which detect carbon dioxide exhaled by mammals, including humans. When they sense carbon dioxide, they whip around and fly upwind, eventually finding the source.

The compounds were originally discovered in experiments with fruit flies, which use the same carbon dioxide-sensing machinery to send each other threat signals. Interestingly, fruit flies' favorite foods, ripe fruit, also give off carbon dioxide; and to stay under cover, the fruits give off their own odor molecules that block the fruit flies' carbon dioxide receptors.

The researchers used these fruity molecules as a starting point for designing repellents, because they figured this group of compounds might have similar effects on mosquitoes (to block their detectors).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Bewildered brains

By studying how these molecules affect mosquitoes in the lab, the researchers figured out how they work: The first group works by binding to the mosquitoes' carbon dioxide receptors in the maxillary palps, stopping the mosquitoes from sending the signal indicating there's a mammal close by when they sense carbon dioxide.

The second group of molecules acts to mimic carbon dioxide's effect on the mosquito — they turn on the carbon dioxide sensing neurons and essentially overwhelm them.

Another group of odor molecules essentially blinds the mosquito to any nearby blood-filled humans by disabling their carbon dioxide-detection machinery. Even a brief exposure to these molecules was enough to confuse the mosquitoes' carbon-dioxide detectors for minutes and severely reduced their sensitivity for minutes afterward.

The group made a mixture of these different odorants to get the maximum effect. The result: Mosquitoes that got a whiff of this compound cocktail were unable to follow a carbon dioxide trail both in the lab and in a study in the field.

They are continuing to test these and similar compounds; though due to some side effects, they can't be used in humans yet and need more testing to determine how safe they are, the researchers report in the June 2 issue of the journal Nature.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus