9 evil medical experiments

Many evil medical experiments have been conducted in the name of science, here are nine of the most horrific.

Throughout history a number of evil experiments have been carried out in the name of science. We all know the stereotype of the mad scientist, often a villain in popular culture. Yet in real-life, while science often saves lives, sometimes scientists commit horrific crimes in order to achieve results.

Some are ethical mistakes, lapses of judgement made by people convinced they're doing the right thing. Other times, they're pure evil. Here are nine of the worst experiments on human subjects in history.

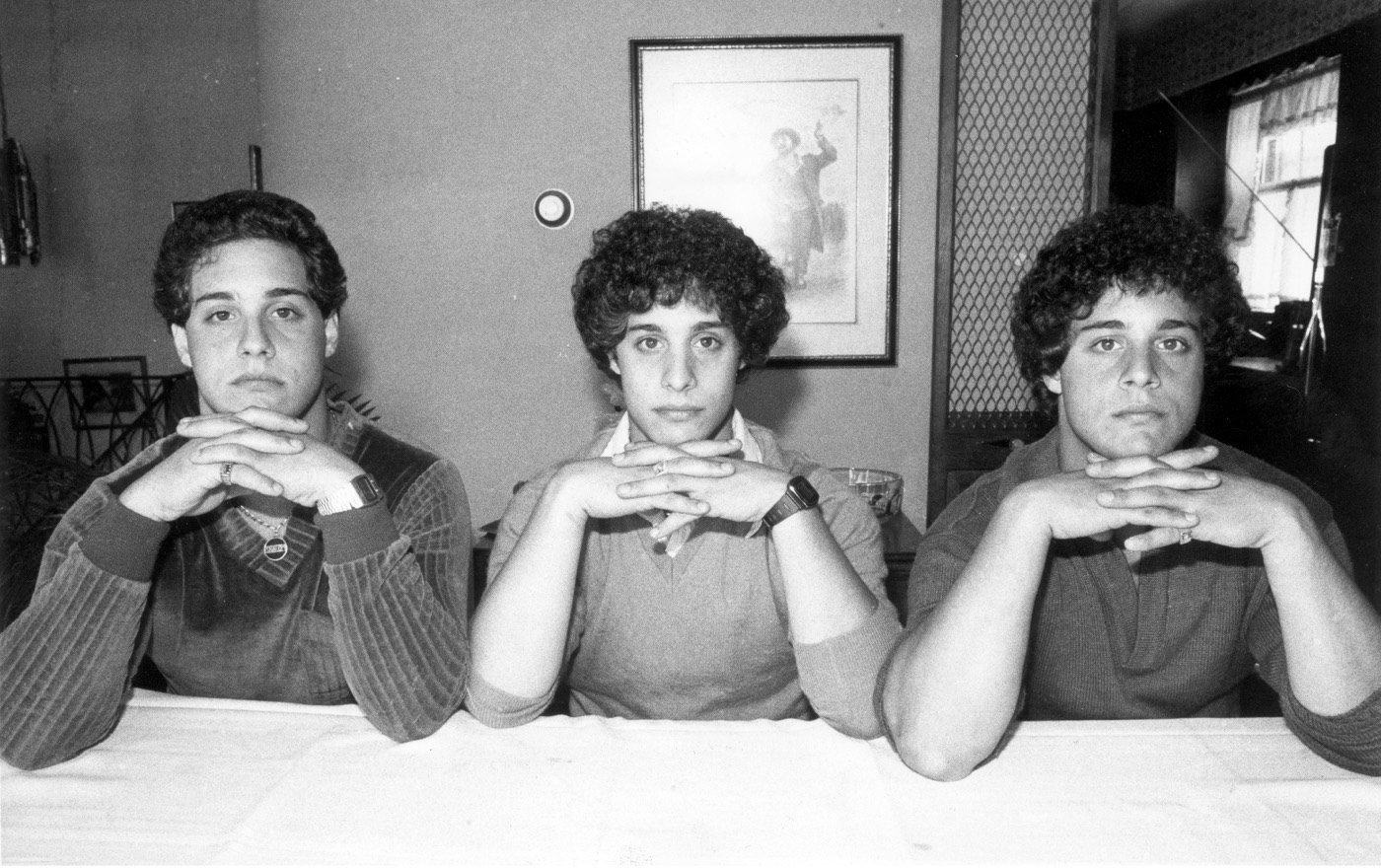

Separating triplets

In the 1960s and 1970s , clinical psychologists led by Peter Neubauer ran a secret experiment in which they separated twins and triplets from each other and adopted them out as singlets. The experiment, said to have been partly funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, came to light when three identical triplet brothers accidentally found each other in 1980. They had no idea they had siblings.

David Kellman, one of the triplets, felt anger towards the experiment: ''We were robbed of 20 years together,'' said Kellman in the Orlando Sentinel article. His brother, Edward Galland died by suicide in 1995 at his home in Maplewood, New Jersey, according to the LA Times.

The child psychiatrists who headed up the study — Peter Neubauer and Viola Bernard — showed no remorse, according to news reports, going as far as saying they thought they were doing something good for the kids, separating them so they could develop their individual personalities, said Bernard, according to Quillette. As for what Neubauer learned from his secret "evil" experiment, that's anyone's guess, as the results of the controversial study are being stored in an archive at Yale University, and they can't be unsealed until 2066, NPR reported in 2007. Neubauer published some of his findings in a 1996 book, Nature's Thumbprint: The New Genetics of Personality, primarily concerning his son. According to Psychology today, as of 2021, some of Dr Viola Bernard's papers have become viewable at Columbia University.

Director Tim Wardle chronicled the lives of the triplets in the film "Three Identical Strangers," which debuted at Sundance 2018.

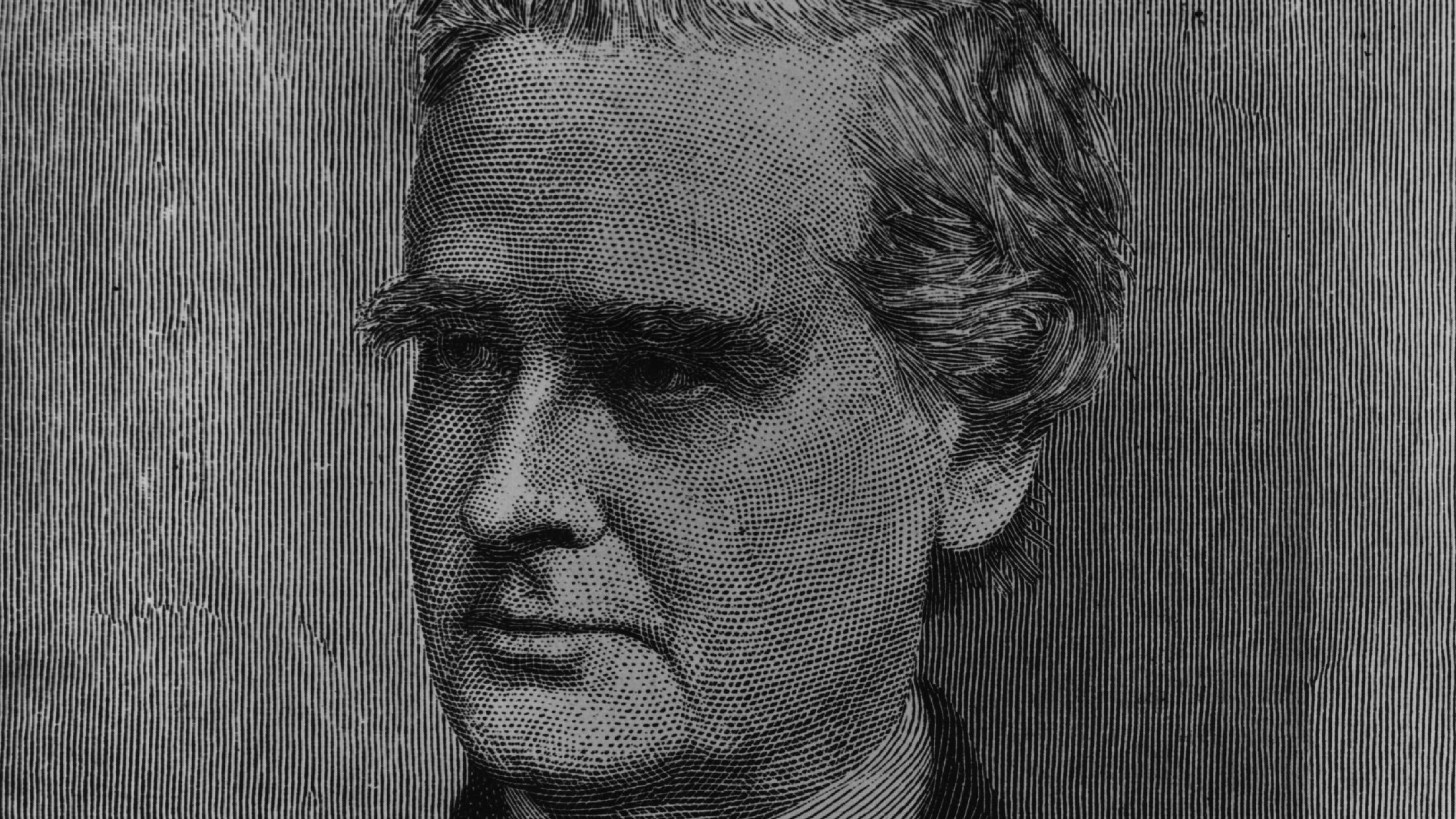

Nazi medical experiments

Perhaps the most infamous evil experiments of all time were those carried out by Josef Mengele, an SS physician at Auschwitz during the Holocaust. Mengele combed the incoming trains for twins upon which to experiment, hoping to prove his theories of the racial supremacy of Aryans. Many died in the process. He also collected the eyes of his dead "patients," according to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Nazis used prisoners to test treatments for infectious diseases and chemical warfare. Others were forced into freezing temperatures and low-pressure chambers for aviation experiments, according to the Jewish Virtual Library. Countless prisoners were subjected to experimental sterilization procedures. One woman, Ruth Elias, had her breasts tied off with string so SS doctors could see how long it took her baby to starve, according to an oral history collected by the Holocaust Museum. She eventually injected the child with a lethal dose of morphine to keep it from suffering longer.

Some of the doctors responsible for these atrocities were later tried as war criminals, but Mengele escaped to South America. He died in Brazil in 1979, of a heart attack, his final years spent lonely and depressed according to The Guardian.

Japan's Unit 731

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, the Japanese Imperial Army conducted biological warfare and medical testing on civilians, mostly in China. Led by General Shiro Ishii, the lead physician at UNIT 731, the death toll of these brutal experiments is unknown, but as many as 200,000 may have died, estimates Historian Sheldon H Harris according to a 1995 New York Times report.

Numerous diseases were studied in order to determine their potential use in warfare. Among them were plague, anthrax, dysentery, typhoid, paratyphoid and cholera, according to a paper by Dr Robert K D Peterson for Montana University. Numerous atrocities were committed including infecting wells with cholera and typhoid and spreading plague-ridden fleas across Chinese cities.

According to Peterson the fleas were dropped in clay bombs, which were dropped at a height of 200-300 meters and showed no trace. Prisoners were marched in freezing weather and then experimented on to determine the best treatment for frostbite.

Former members of the unit have told media outlets that prisoners were dosed with poison gas, put in pressure chambers until their eyes popped out, and even dissected while alive and conscious. After the war, the U.S. government helped keep the experiments secret as part of a plan to make Japan a cold-war ally, according to the Times report.

It was not until the late 1990's that Japan first acknowledged the existence of the unit and not until 2018 that the names of thousands of members of the Unit were disclosed, according to The Guardian.

The "monster study"

In 1939, speech pathologists at the University of Iowa set out to prove their theory that stuttering was a learned behavior caused by a child's anxiety about speaking. Unfortunately, the way they chose to go about this was to try to induce stuttering in orphans by telling them they were doomed to start stuttering in the future.

The researchers sat down with children at the Ohio Soldiers and Sailors Orphans' Home and told them they were showing signs of stuttering and shouldn't speak unless they could be sure that they would speak right. The experiment didn't induce stuttering, but it did make formerly normal children anxious, withdrawn and silent.

Future Iowa pathology students dubbed the study, "the Monster Study," according to a 2003 New York Times article on the research. Three surviving children and the estates of three others eventually sued Iowa and the university. In 2007, Iowa settled for a total of $925,000.

The Burke and Hare murders

Until the 1830s, the only legally available bodies for dissection by anatomists were those of executed murderers. Executed murderers being a relative rarity, many anatomists took to buying bodies from grave robbers — or doing the robbing themselves. “Body snatching as a ‘professional’ occupation didn’t really start to take shape until the end of the 18th century” Suzie Lennox, the author of Bodysnatchers: Digging Up the Untold Stories of Britain's Resurrection Men told All About History in an interview “up till then the students and anatomists would have carried out their own raids in graveyards, acquiring cadavers as and when they could”.

Edinburgh boarding house owner William Hare and his friend William Burke found a way to deliver fresh corpses to Edinbrugh's anatomy tables without ever actually stealing a body. From 1827 to 1828, the two men smothered more than a dozen lodgers at the boarding house and sold their bodies to anatomist Robert Knox, according to Mary Roach's "Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers" (W.W. Norton & Company, 2003). Knox apparently didn't notice (or didn't care) that the bodies his newest suppliers were bringing him were suspiciously fresh, Roach wrote.

Burke was later hanged for his crimes, and the case spurred the British government to loosen the restrictions on dissection. "The scandal led to the Anatomy Act of 1832 which made greater numbers of cadavers legally available to schools" Maclolm McCallum, the curator of the Edinburgh Anatomical Museum told All About History in an interview. "If you died in an asylum or hospital, and had no relatives or means to cover your funeral costs, your body would go to the schools for dissection. Crucially, the institutions which were providing the cadavers only supplied them to anatomy schools that were associated with teaching hospitals".

Surgical experiments on slaves

The father of modern gynecology, J. Marion Sims, gained much of his fame by doing experimental surgeries (sometimes several per person) on slave women, according to The Atlantic. Sims remains a controversial figure to this day, because the condition he was treating in the women, vesico-vaginal fistula, caused terrible suffering. Women with fistulas, a tear between the vagina and bladder, were incontinent and were often rejected by society.

Sims performed the surgeries without anesthesia, in part because anesthesia had only recently been discovered, and in part because Sims believed the operations were "not painful enough to justify the trouble," as he said in alecture according to NPR.

Arguments still rage as to whether Sims' patients would have consented to the surgeries had they been entirely free to choose. Nonetheless, wrote University of Alabama social work professor Durrenda Ojanuga in the Journal of Medical Ethics in 1993, Sims "manipulated the social institution of slavery to perform human experimentations, which by any standard is unacceptable." In 2018, a statue of Sims was removed in response to the ongoing controversy, according to The Guardian.

Guatemala syphilis study

Many people erroneously believe that the government deliberately infected the Tuskegee participants with syphilis, which was not the case. But the work of professor Susan Reverby recently exposed a time when the U.S. Public Health Service researchers did just that, according to Wellesley College. Between 1946 and 1948, Reverby found, the U.S. and Guatemalan governments co-sponsored a study involving the deliberate infection of 1,500 Guatemalan men, women and children with syphilis according to The Guardian.

The study was intended to test chemicals to prevent the spread of the disease. According to Michael A. Rodriguez in a 2013 paper; "The experiments were not conducted in a sterile clinical setting in which bacteria that cause STDs were administered in the form of a pin prick vaccination or a pill taken orally. The researchers systematically and repeatedly violated profoundly vulnerable individuals, some in the saddest and most despairing states, and grievously aggravated their suffering" Those who got syphilis were given penicillin as a treatment, Reverby found, but the records she uncovered indicate no follow-up or informed consent by the participants. On Oct. 1, 2010, Secretary of State Hilary Clinton and Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius issued a joint statement apologizing for the experiments, according to The Guardian.

The Tuskegee study

The most famous lapse in medical ethics in the United States lasted for 40 years. In 1932, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the U.S. Public Health Service launched a study on the health effects of untreated syphilis in black men.

The researchers tracked the progression of the disease in 399 black men in Alabama and also studied 201 healthy men , telling them they were being treated for "bad blood." In fact, the men never got adequate treatment, even in 1947 when penicillin became the drug of choice to treat syphilis. It wasn't until a 1972 newspaper article exposed the study to the public eye that officials shut it down, according to the official Tuskegee site.

The Stanford Prison Experiment

In 1971, Philip Zimbardo, now professor emeritus of psychology at Stanford University, set out to test the "nature of human nature," to answer questions such as "What happens when you put good people in evil situations?" How he went about answering his human nature questions was and is thought by many to have been less than ethical. He set up a prison and paid college students to play guards and prisoners, who inevitably seemed to transform into abusive guards and hysterical prisoners. The two-week experiment was shut down after just six days because things turned chaotic fast. "In only a few days, our guards became sadistic and our prisoners became depressed and showed signs of extreme stress," Zimbardo stated, according to Times Higher Education. The guards, pretty much from the get-go, treated the prisoners awfully, humiliating them by stripping them naked and spraying their bodies with delousing chemicals and generally harassing and intimidating them, according to the Stanford Prison Experiment site

Turns out, according to a report on Medium, a news publication, in June 2018, the guards didn't become aggressive on their own — Zimbardo encouraged the abusive behavior — and some of the prisoners faked their emotional breakdowns. For instance, Douglas Korpi, a volunteer prisoner said that he faked a meltdown to get released early so he could study for an exam.

Even so, the Stanford Prison Experiment has been the basis of psychologists' and even historians' understanding of how even healthy people can become so evil when placed in certain situations, according to the American Psychological Association.

Additional Resources:

For more concerning the atrocities committed during the Holocaust, check out the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. The New York Times original 1995 report on the events that occured at Manchu 731 is available here. Those interested in the Stanford Prison Experiment should check out the experiments website.

Related Links:

Bibliography:

- Amy Kaufman: "The surreal, sad story behind the acclaimed new doc ‘Three Identical Strangers" Los Angeles Times, July 1 2018

- Nancy L Segal: "Shame and Silence: The LWS Twin Studies Revisited" Quillette, 26th Sep 2021

- Holocaust Encyclopedia: Josef Mengele

- Dachau: High Altitude Experiments, Jewish Virtual Library

- Jan Rocha, "Mengele Letters Reveal Life Ended in Pain and Poverty", The Guardian, 23 Nov 2004

- Nicholas D Kristoff: "Unmasking Horror - A Special Report" The New York Times, March 17th 1995

- Dr Robert K D Peterson: "Japan’s Role in Developing Biological Weapons in World War II and its Effect on Contemporary Relations between Asian Countries" Montana State University

- Justin McCurry: "Unit 731: Japan discloses details of notorious chemical warfare division" The Guardian, 17th April 2018

- Gretchen Reynolds: "The Stuttering Doctor's 'Monster Study", New York Times, March 16th 2003

- Mary Roach's "Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers" (W.W. Norton & Company, 2003)

- Sarah Zhang: "The Surgeon Who Experimented on Slaves", The Atlantic, April 18th 2018

- Camila Domonoske: "Father Of Gynecology,' Who Experimented On Slaves, No Longer On Pedestal In NYC" NPR, April 17th 2018

- Durrenda Ojanuga: "The Medical Ethics of the 'Father of Gynaecology', Dr J Marion Sims' Journal of Medical Ethics, 1993

- Nadja Sayej: "J Marion Sims: controversial statue taken down but debate still rages", The Guardian, Sat 21st April 2018

- Rory Caroll, "Guatemala victims of US syphilis study still haunted by the 'devil's experiment", The Guardian, 8th June 2011

- Michael A Rodriguez, National Library of Medicine

- Chris McGreal: "US says sorry for 'outrageous and abhorrent' Guatemalan syphilis tests", The Guardian, 1st October 2010

- Matthew Reisz, "Re-engaging with the Stanford Prison Experiment". Times Higher Education, Sep 26th 2018

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.