Who invented the telephone?

Did Alexander Graham Bell really invent the telephone, or did he steal someone else's thunder?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

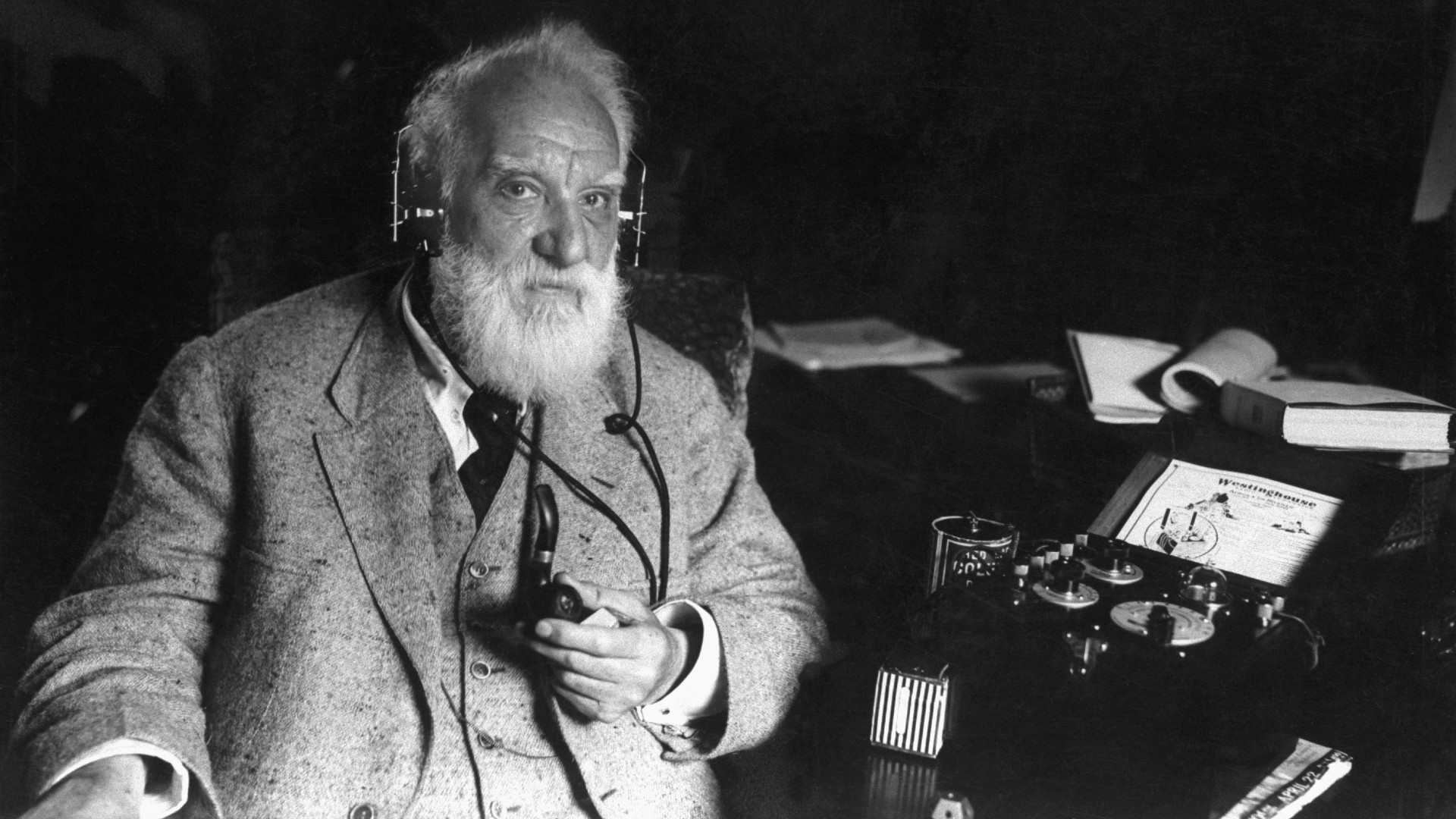

Phones are integral to the everyday lives of most people, but who should be regarded as the device's mastermind? The Scottish-born Alexander Graham Bell is routinely credited as the inventor of the telephone and the first person to speak over the phone. In that first telephone call, on March 10, 1876, he famously told his assistant Thomas Watson, "Mr. Watson, come here; I want to see you."

But, as Iwan Morus explains in his book "How the Victorians Took Us to the Moon: The Story of the 19th-Century Innovators Who Forged Our Future" (Icon Books, 2022), inventions are rarely the results of a sole pioneer.

"Many — I'd almost say all — nineteenth-century electrical inventions were highly contested, with different inventors claiming credit for having solved the key problems first," Morus told Live Science in an email. "Charles Wheatstone and William Fothergill Cooke, the co-patentees of the first British electromagnetic telegraph, for example, didn't take long to fall out over which of them really invented it. Samuel Morse quarreled with pretty much everyone about his claims to inventing the telegraph. And there were similar debates about the lightbulb, and so on."

Related: 20 inventions that changed the world

Likewise, many people other than Bell claimed to have invented the telephone, Christopher Beauchamp, a professor of law at Brooklyn Law School, wrote in a 2010 article in the journal Technology and Culture. In fact, some people even suggested that "Bell seized the honor fraudulently," Beauchamp said.

"It's not surprising that Bell's claims were contested," Morus added. "There was a lot of money, as well as fame, at stake. However, as a historian, I'm less interested in deciding who really invented something, and more interested in how particular individuals emerged from the pack to win the credit."

Italian inventor Antonio Meucci (who was belatedly honored by U.S. House of Representatives for his contributions to the telephone's invention in 2002); American engineer Elisha Gray; and German physicist Johann Philipp Reis, who constructed the first "make-and-break" telephone in 1861, all played roles in the development of the telephone.

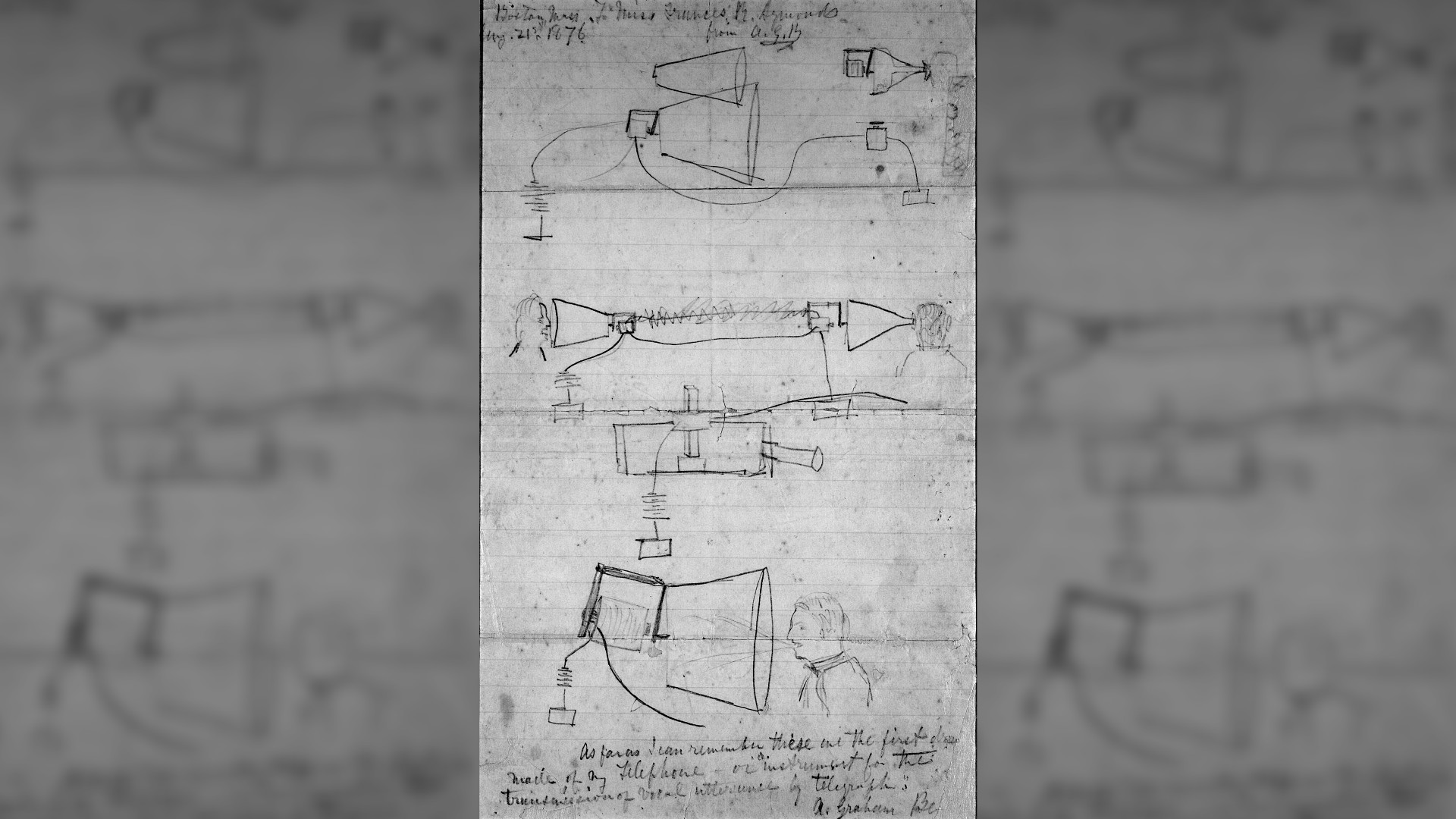

Reis' contraption was slightly different to Bell's more refined solution. Reis' worked by a process of making and breaking connections with a circuit. His device was able to capture sound and then convert it to electrical impulses, which could then be transmitted via electrical wires to another device that, in turn, was able to convert them into sounds. The system was reliant on connections being repeatedly made and then broken, which meant that, unlike Bell's device, a continuous conversation was not possible.

That is partly why Bell's name has stood the test of time, but, according to Beauchamp,the overwhelming reason is somewhat more bureaucratic: patent law.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the 1880s, "in one of the largest and most controversial litigation campaigns of any kind during the nineteenth century," Beauchamp wrote in his article, Bell hired a collective of high-profile, powerful attorneys, who won a spate of patent cases that resulted in the telephone industry coming under a "legal monopoly." The courts declared Bell's claims that he pioneered the telephone's technology to be true and, as a result, awarded him "broad rights over electrical speech communication," Beauchamp explained.

It is worth noting that both Bell and Gray submitted independent telephone-centric patents on Feb. 14, 1876. And while Gray's application arrived at the patent office ahead of Bell's, Bell's lawyers were more proactive than Gray's and paid the application fees as soon as possible. Consequently, Bell's application was seen and registered first and ended up being approved and registered on March 7, three days before his famous call with Watson.

Related: How do fax machines work?

But what, exactly, did Bell invent? "The key to the telephone was finding a way to turn the vibrations caused by the voice into a varying electric current, and turning those electric variations back into acoustic vibrations at the other end," Morus said. "Bell's real breakthrough was finding a way of doing that reliably." This, Morus notes, is what made Bell's device superior to Reis'.

However, Bell's ability to create a narrative may have played an important role. A year after Bell got the patent, his father-in-law Gardiner Greene Hubbard organized the new Bell Telephone Company. "In Bell's case, I think it was partially a matter of having an appealing inventor-story to tell," Morus said, "and the fact that his telephone company was quick to take off and remained dominant in the US for so long."

Another factor in Bell's legacy is his focus on transmitting vocals, as opposed to written messages. "What struck people at the time was the transmission of the human voice, in particular," Morus said. "Telegraphy was big business by the 1870s on both sides of the Atlantic, and inventors — including Bell — were competing to find ways of sending messages more and more efficiently. Ironically, not many of Bell's competitors were all that interested in transmitting the voice because, they thought, it simply wasn't an efficient enough means of transmitting information.

Though some may disagree about who should be credited as the inventor of the telephone, it's clear that it was one of the most influential and important inventions of the Victorian era. "I think the key thing about the telephone was the way it brought the electrical future (so to speak) right into the Victorian middle class home," Morus said. "It was a vital component in the way the Victorians thought the future would be."

Joe Phelan is a journalist based in London. His work has appeared in VICE, National Geographic, World Soccer and The Blizzard, and has been a guest on Times Radio. He is drawn to the weird, wonderful and under examined, as well as anything related to life in the Arctic Circle. He holds a bachelor's degree in journalism from the University of Chester.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus