What is the vaginal microbiome?

The vaginal microbiome is made up of around 300 species of bacteria. But its links to health are still being uncovered.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The vaginal microbiome is the community of the bacteria and other microorganisms that live in the vagina.

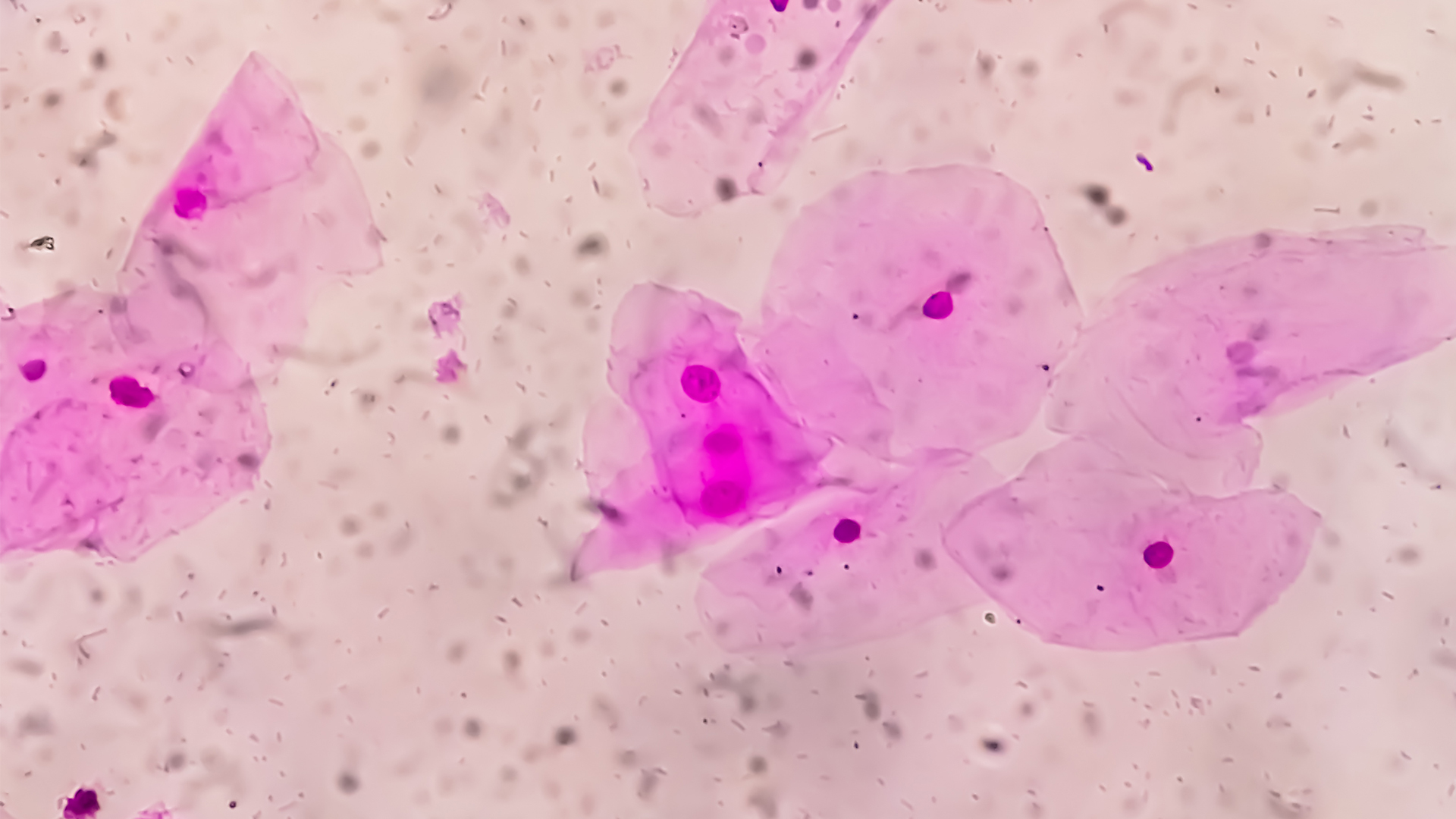

Many people think of the term "vaginal microbiome" as chiefly referring to the vagina's bacterial environment, which includes more than 300 bacteria species, according to a 2020 study published in the journal Nature Communications. However, the microbiome also includes non-bacterial organisms in the vagina, such as yeasts, as well as viruses — although viruses are not technically "alive."

A person's vaginal microbiome changes throughout their lifetime and in response to specific events.

"We have the menstrual cycle, we have sex, we have childbirth, menopause, and all those kinds of things," said Dr. Vanessa Barnabei, a professor emeritus of obstetrics and gynecology at the University at Buffalo in New York. "So everything affects the organisms that are growing."

Barnabei is an expert on obstetrics and gynecology and women’s health. She has practiced for many years as a physician, with particular expertise on caring for women with menopausal and perimenopausal problems. For many years, she has also focused her practice on women with vulvar disorders such as pain and lichen sclerosus.

What bacteria are found in the vagina?

In many people with healthy vaginal microbiota, bacteria called Lactobacillus dominate the vagina. Lactobacillus is a bacterial genus that includes many different species. A vaginal microbiome dominated by Lactobacillus is thought to be optimal, according to a 2021 review article published in Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, and is often associated with decreased risk of a variety of negative health outcomes.

Lactobacillus can make up as much as 99.9% of vaginal bacteria, said Jacques Ravel, a professor of microbiology and immunology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. A single Lactobacillus species can even make up 95% to 99% of the vaginal microbiome, Dr. Seth Bloom, an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School and an infectious disease physician-scientist at Massachusetts General Hospital, told Live Science.

Though white people of European ancestry most often have microbiota dominated by Lactobacillus species, it's far more common for Black and Hispanic people to have microbiota that aren't dominated by these species, said Barnabei.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Although exactly what these bacteria do is still unclear, they could have several roles in keeping the vagina healthy. They produce antiinflammatory substances, Barnabei said, as well as lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide, which help maintain the acidic environment of the vagina, and suppress the growth of potentially harmful bacteria and yeast.

A 2022 study published in the journal Microbiome also suggested that lactic acid secreted by vaginal microbiota helps strengthen the barrier of tissue lining the vagina, protecting it from bacteria and other pathogens that can cause sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV.

What diseases are linked to the vaginal microbiome?

Disruptions to the microbiome that change the vagina's pH are linked to infection.

People whose vaginal microbiomes are dominated by bacteria other than Lactobacillus may develop a condition called bacterial vaginosis (BV). Usually, these other bacteria are anaerobic bacteria, or bacteria that don't use oxygen, with one of the most common species being Gardnerella vaginalis. BV can lead to symptoms such as vaginal itching, burning and an unpleasant smell sometimes described as "fishy," Barnabei said. Pregnant women with BV also have around a two-fold higher risk of miscarriage than those without BV, according to a 2021 review in the journal Frontiers in Microbiology, while infertility and uterine fibroids are also linked, the review notes.

However, not everyone with relatively little Lactobacillus has symptoms of BV. Black and Hispanic people may be less likely to have a Lactobacillus-dominated microbiome. In a 2010 study of the vaginal microbiota of North American women by Ravel and other researchers, published in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, about 80% of Asian women and 90% of white women in the study group had microbiota dominated by Lactobacillus. In Black and Hispanic study participants, only 60% did. None of the women in the study had BV symptoms.

"There are women that we've studied [where] we looked at their microbiome on a daily basis for 10 weeks, and they have no Lactobacillus," Ravel said. "And… they appear to be perfectly fine. They don't report any symptoms." Ravel and other researchers documented a patient like this in a 2013 study published in the journal Microbiome, however, it is unusual.

BV is treated using antibiotics, Ravel said, which can be taken in pill form or applied as a gel directly to the vagina. These antibiotics are usually taken for seven days, though some of the available gels, and an oral antibiotic called secnidazole, are applied or taken only once.

For decades, antibiotics have been the only treatment option for BV, but they often don't work, Bloom said. A 2006 study published in The Journal of Infectious Diseases found that 58% of participants with BV symptoms saw the symptoms return within a year of treatment.

For people who get BV repeatedly, as many as 80% have their BV return after treatment, Bloom said. In a 2020 study published in Clinical Infectious Disease where women with recurrent BV (and sometimes their partners) were treated with antibiotics, about 80% had BV again within 16 weeks of finishing treatment. Other risk factors for developing BV, according to the U.K.’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, include being sexually active, using deodorant and vaginal washes, smoking and having an IUD.

Despite this, it's important that if you are prescribed a multi-day course of antibiotics for BV, you should complete the course for the best chance of it being effective, Barnabei said — especially if you've never had BV or don't tend to get it chronically.

In pregnant people, who are at an increased risk of having BV, a non-optimal vaginal microbiome is associated with an increased risk of complications, Barnabei said, including preterm birth and miscarriage. A 2019 study published in the British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology found an association between a microbiome depleted of Lactobacillus and an increased risk of miscarriage in the first trimester of pregnancy. Another study, published in 2021 in the journal Nature Scientific Reports, found that researchers could predict the likelihood that pregnant people would have an infection of the placenta during pregnancy from a less Lactobacillus-dominated microbiota sample.

Vaginal microbiome research

Many aspects of the vaginal microbiome still aren't well-understood, particularly when it comes to BV.

After decades of prescribing only antibiotics to treat BV, researchers are working to develop new treatments. There isn't much evidence that taking oral probiotics — a supplement that contains live microorganisms — is helpful for treating BV, Ravel said, but new probiotics, also called live biotherapeutic drugs, delivered directly into the vagina, are in development and have shown some positive results when combined with an antibiotic. In a recent clinical trial, described in a 2020 report published in the New England Journal of Medicine, researchers concluded that a live biotherapeutic drug called Lactin-V significantly reduced the recurrence of BV in participants when used with an antibiotic, compared with a group who took the same antibiotic and a placebo drug. The Lactin-V helped to repopulate the vagina with "good" bacteria after the antibiotic, the researchers said.

Some studies show that BV may not only emerge when Lactobacillus gets crowded out by other types of bacteria, but also when the ratio of different Lactobacillus species shifts in the vagina. For example, symptoms of BV may emerge when Lactobacillus iners outgrows Lactobacillus crispatus. In a 2022 study published in the journal Nature Microbiology, Bloom and his colleagues examined a potential way to induce Lactobacillus crispatus dominance and thus correct imbalances in the vaginal microbiome, by combining an antibiotic with a method of blocking cells' uptake of an amino acid called cysteine in cells grown in the lab.

Recent research has also examined the role of the vaginal microbiome in the transmission of HIV. In 2017, a landmark study in the journal Immunity showed that a group of young South African women who had vaginal microbiomes dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus were dramatically less likely to contract HIV within the study's follow-up period than those with microbiota dominated by several types of anaerobic bacteria. A 2021 study in Frontier in Immunology also suggested that failure of antibiotic treatment for BV promoted an inflammatory response that could make people more vulnerable to HIV and other STIs.

Bloom said that new research has the potential to help understand a condition that has been chronically under-researched.

"There's really, I think, a really large benefit to be gained if we can get a better understanding of these diseases and develop better interventions to both diagnose and treat people," he said.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Rebecca Sohn is a freelance science writer. She writes about a variety of science, health and environmental topics, and is particularly interested in how science impacts people's lives. She has been an intern at CalMatters and STAT, as well as a science fellow at Mashable. Rebecca, a native of the Boston area, studied English literature and minored in music at Skidmore College in Upstate New York and later studied science journalism at New York University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus