A planet-size sunspot grew 10-fold in the last 2 days, and it's aimed directly at Earth

The region could send unexpected solar flares our way.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists have detected a rapidly growing sunspot that’s pointed directly at Earth and could launch an assault of solar energy our way in the coming days.

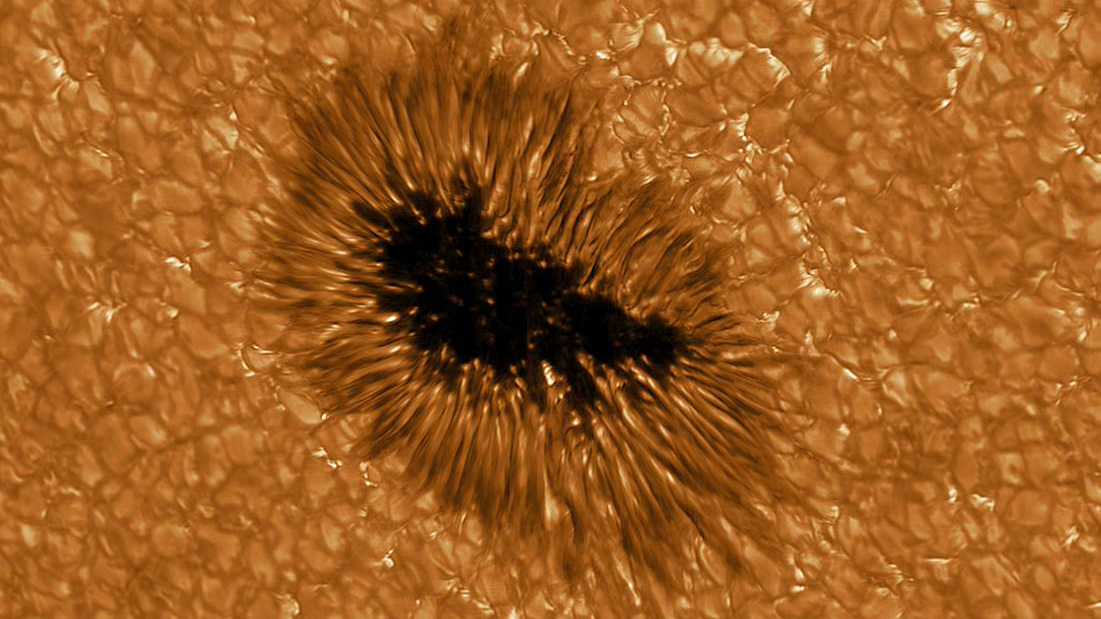

The sunspot, named AR3085 for the "active region" of the sun in which it appeared, was barely a blip several days ago. Now, it has grown 10 times bigger, morphing into a pair of sunspots that each measure nearly the diameter of Earth, according to SpaceWeather.com. This short gif shows the spot's evolution over about two days.

A number of solar flares — large explosions of electromagnetic radiation that snap off from the sun's surface and launch outward into space— have been detected "crackling" around the spot, according to SpaceWeather. Fortunately, they are all currently C-class flares, which fit into the weakest of the three tiers of solar flares that government satellites track. A-, B- and C-class flares are generally too weak to have a noticeable impact on Earth. M-class flares are stronger, capable of causing radio blackouts at high latitudes, while X-class flares are the strongest and can cause widespread radio blackouts, damage satellites and knock out ground-based power grids, according to NASA.

If the spots continue to grow over the coming days, they could produce stronger flares that could barrel toward Earth, potentially endangering satellites and communication systems. For now, however, there is no imminent danger.

Sunspots are large, dark regions of strong magnetic fields that form on the sun's surface. These regions — which typically measure as wide as planets — appear darker because they are cooler than their surroundings, according to Live Science's sister site Space.com. They form where bands of the sun's magnetic field become tangled and taut, inhibiting the flow of hot gas from the sun's interior and forming cooler, darker regions on the sun's surface.

These pile-ups of magnetic energy often lead to solar flares. The more sunspots that appear on the sun at a given time, the more likely solar flares are to erupt.

The prevalence of both sunspots and solar flares are linked to the sun's 11-year cycle of activity, which transitions between periods of high and low sunspot density every decade or so. The next solar maximum — or the period of highest sunspot activity — is predicted to hit in 2025, with as many as 115 sunspots likely to appear on the sun's surface during its days of peak activity.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Solar activity has been ramping up over the last few years, with numerous X-class flares swooping over our planet since spring 2022 — sometimes within days of one another. The number of sunspots and solar flares will likely increase as time ticks toward the next solar maximum.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus