Japan's 'Moon Sniper' lands on lunar surface, but it may be dead within hours

Japan's SLIM lander successfully landed on the lunar surface on Friday, Jan. 19, but problems with its solar cells mean it could be dead on the moon within hours.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

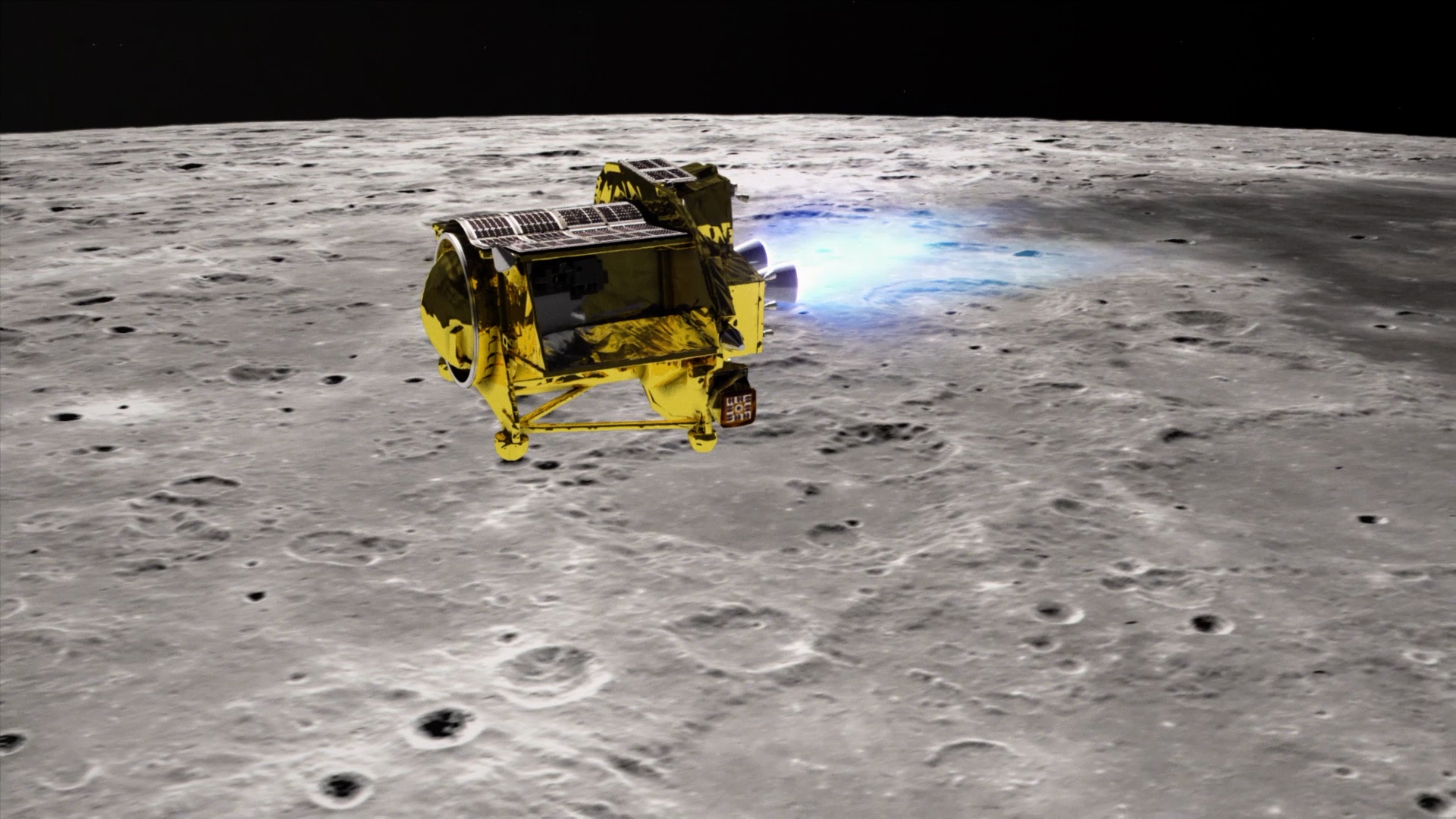

Japan successfully became the fifth nation to land on the moon on Friday (Jan. 19), when the country's robotic Smart Lander for Investigating the Moon (SLIM) successfully descended to the lunar surface at 10:20 a.m. EST (or 12:20 a.m. on Saturday, Jan. 20 in Japan).

The craft seems to have succeeded in making a soft landing on the moon, as SLIM is currently sending and receiving data from its new home near Shioli crater on the lunar near-side, mission officials said in a televised press conference on Friday. However, the lander may only survive for a few hours there following an error with the lander's solar energy cells, which are not generating electricity as expected, the officials said.

SLIM is currently running on reserve battery power, which will likely run out within a few hours. That gives researchers a limited time to carry out science operations with the lander before it goes offline. SLIM's solar cells may yet be able to generate electricity if the orientation of incoming sunlight changes and hits the panels in the coming weeks, the officials added. However, the lander's ultimate fate remains uncertain.

Despite this setback, Japan joins the United States, Russia, China and India as the only nations to successfully land a spacecraft on the moon.

Related: The Apollo moon landing was real, but NASA's quarantine procedure was not

SLIM — built by Japan's space agency (JAXA) and nicknamed the "Moon Sniper" — was designed to demonstrate a new navigation system capable of achieving pinpoint landings on the lunar surface. The mission's goal was to land the craft within a scant 330 feet (100 meters) of its target landing site, near the rim of Shioli crater, according to Live Science's sister site Space.com. It could take up to a month to verify how close the craft landed to its target, JAXA has said.

SLIM launched from Japan's Tanegashima Space Center in Minamitane on Sept. 6, 2023, and it reached a lunar orbit on Dec. 25. The craft spent the following weeks orbiting the moon and testing various systems before attempting its landing on Friday.

SLIM, which measures about the size of a small truck, carried two robotic rovers with it, named Lunar Excursion Vehicle 1 and 2 (LEV-1 and LEV-2). The mission called for SLIM to deploy the two rovers during its attempted landing — and one of them (LEV-1) seems to be online.

This was not Japan's first attempted lunar landing. Last year, the private Japanese company ispace attempted to land its Hakuto-R lunar lander, but ground controllers lost contact with the craft during its descent on April 25, resulting in a crash landing. Earlier, in November 2022, a small lander named OMOTENASHI hitched a ride on NASA's uncrewed Artemis I mission. The tiny lander failed to survive its descent to the lunar surface, while the Artemis capsule continued its mission around the moon and then back to Earth.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Several recent lunar landing attempts made by other nations and private companies have also gone awry.

On Jan. 8, the Peregrine lunar lander designed by U.S.-based space company Astrobotic Technology suffered a critical propellant leak just hours after launching, dooming the craft to burn up in Earth's atmosphere instead of completing its trip to the moon. And in August 2023, Russia's Luna 25 lander crashed into the moon's south pole during its attempted landing, leaving a new 33-foot-wide (10 m) crater behind.

Several weeks later, India's Chandrayaan-3 lander successfully landed at the lunar south pole, making India the first nation to land there, and the fourth to make a soft landing on the moon. However, the craft only remained operational for about a month before losing power.

The lunar south pole is a popular target for future space missions, due largely to the abundance of frozen water locked up in permanently shadowed craters there.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus