Explosive 'devil comet' grows seemingly impossible 2nd tail after close flyby of Earth — but it's not what it seems

Comet 12P/Pons-Brooks, also known as the devil comet, recently made its closest approach to Earth for more than 70 years. During this close encounter, astrophotographers spotted a seemingly impossible "anti-tail" coming off the comet thanks to an extremely rare optical illusion.

The explosive, green "devil comet" that recently swept close to Earth appeared to grow an impossible second tail as it passed us, new photos reveal. But this extra limb, known as an anti-tail, is actually an extremely rare optical illusion caused by the comet's proximity to our planet.

12P/Pons-Brooks (12P) is a 10.5-mile-wide (17 kilometers) comet with a green hue, which is given off by pairs of carbon atoms, known as dicarbon, in its tail and coma — the cloud of gas that surrounds its icy crust, or nucleus. 12P is cryovolcanic, meaning it occasionally erupts when solar radiation superheats the comet's icy innards, or cryomagma, causing pressure to build up in the nucleus until the core splits and shoots its guts into space. When this happens, the comet's coma expands and reflects additional light, making the comet shine brighter than normal.

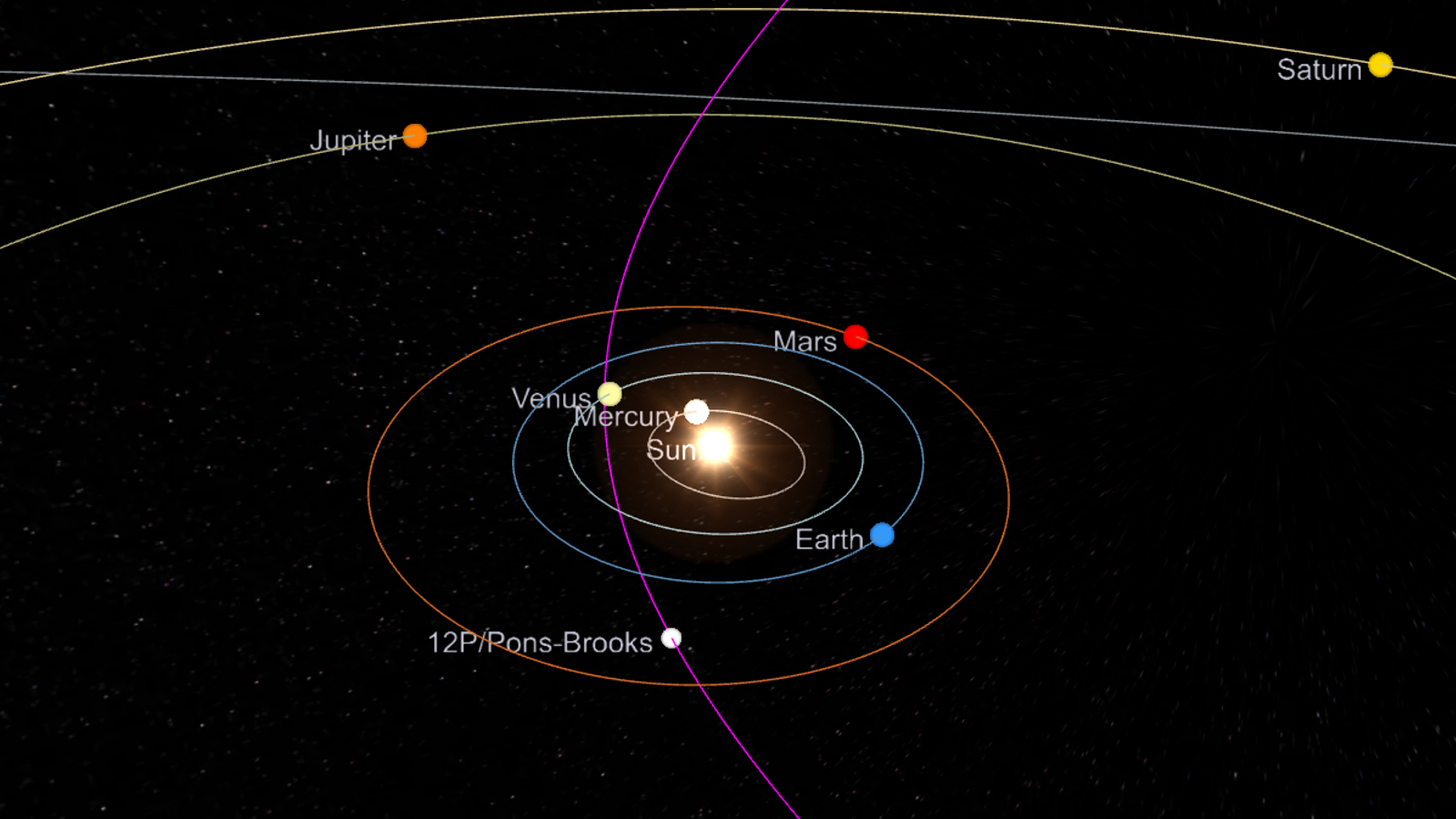

12P spends the majority of its highly elliptical, 71.3-year orbit around the sun out of sight in the Oort Cloud — a reservoir of comets toward the edge of the solar system. But in the last year, the comet sped through the inner solar system as it made its closest approach to the sun. And as it got closer to our home star, it frequently erupted.

During the comet's initial eruptions last year, its expanded coma grew, giving the impression that it had grown a pair of demonic horns, which earned it its sinister nickname. But these horns did not appear in subsequent eruptions.

12P made its closest approach to the sun since 1953 on April 21 this year when it slingshotted around our home star and began heading back out toward the outer solar system. On June 2, the comet made its closest approach to Earth, when it reached a distance of around 1.5 astronomical units from our planet, which is approximately 1.5 times further away from Earth than the sun.

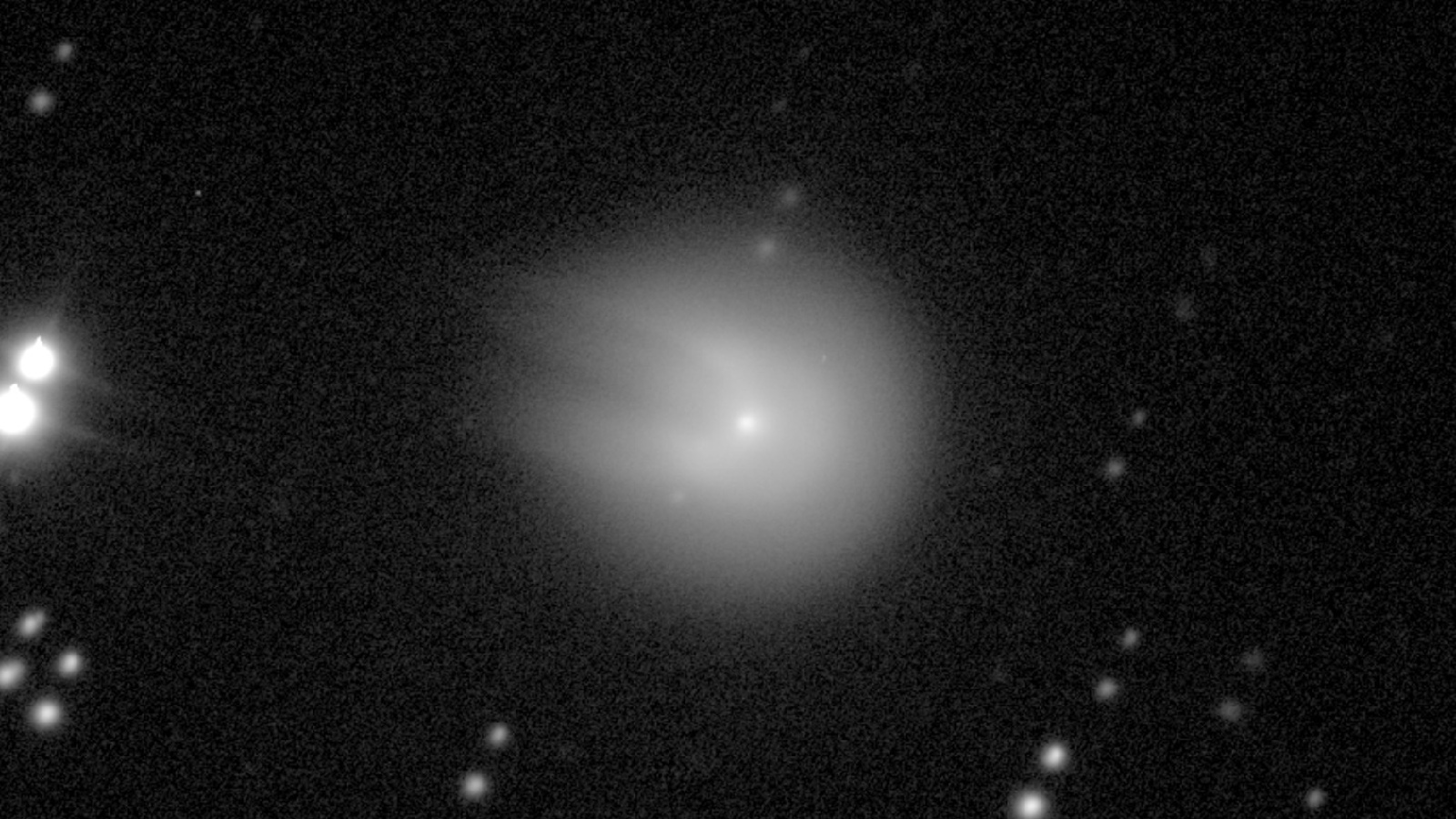

On June 3, astrophotographers Michael Jäger, Gerald Rhemann and Lukas Demetz captured a striking photo of 12P from Namibia. In addition to its normal blurry tail, the comet sported a much longer and sharper tail known as an anti-tail, in this photo, which appeared to point in the opposite direction to the other tail.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This secondary tail seemingly defies physics because a comet's tail is created when dust and gas are blown off its surface by solar wind, meaning the structure stretches away from the sun. But in the new photo, the anti-tail is pointing directly toward the sun.

However, the comet had not actually grown another tail. Instead, we are seeing light reflecting off the gas and dust left behind in the comet's wake. Normally, this is invisible to us. But when Earth passes through the comet's orbital plane, as it did on June 3, this trail of debris is illuminated by the sun, according to Spaceweather.com.

This illusion is similar to how the Milky Way often appears as a bright band across an unpolluted night sky because we are looking at the galaxy's plane side-on.

Comet anti-tails are rare. The last documented case was an anti-tail on the green comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF), which made its closest approach to Earth in February 2023. Before then, anti-tails were also spotted on Comet Kohoutek in 1973, Comet Hale–Bopp in 1997 and Comet PanSTARRS in 2013, Live Science previously reported.

This is not the first time that 12P's tail has made headlines. Back in April, when the comet was preparing to slingshot around the sun, 12P's main tail was temporarily ripped off by a solar storm — a phenomenon known as a disconnection event.

When the comet was at its closest point to our home star, it was also visible to the naked eye from Earth. However, it is no longer possible to see the comet in the night sky without a good telescope.

12P is now on the long journey back toward the outer edges of the solar system and will not return to the inner solar system until around 2095.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus