Volcanic 'devil comet' racing toward Earth resprouts its horns after erupting again

The massive volcanic comet 12P/Pons-Brooks, which grows giant horns when it erupts, has exploded for a third time in five months as it continues to race toward the sun.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A volcanic "devil comet" that is racing toward Earth erupted again on Halloween, causing it to regrow its distinctive "horns." The latest outburst, which was the second within a month and the third since July, is a reminder that the comet is becoming more volcanically active as it continues its journey toward the heart of the solar system.

The comet, named 12P/Pons-Brooks (12P), is a cryovolcanic, or cold volcano, comet. Like other comets, 12P has a solid nucleus — a hard, icy shell filled with ice, gas and dust — that is surrounded by a fuzzy cloud, or coma made of materials that leak out of the comet's insides.

But unlike non-volcanic comets, radiation from the sun can superheat 12P's interior, causing pressure to build up until it becomes so intense it cracks the nucleus' shell from the inside and sprays its icy guts into space. These eruptions cause the comet's coma to expand and brighten as it reflects more sunlight toward Earth.

When the comet erupts, its coma forms iconic devil "horns." These occur because 12P's large nucleus, which spans around 10.5 miles (17 kilometers) across, has an unusual "notch" on its surface, which blocks the outflow of cryomagma into space and causes its expanded coma to grow with an irregular shape.

Related: Watch the biggest-ever comet outburst spray dust across the cosmos

On July 20, astronomers spotted 12P blow its top for the first time in 69 years when its misshaped coma grew to more than 7,000 times wider than its nucleus. Then, on Oct. 5, experts watched as the comet exploded again with even greater intensity.

And last week, on Oct. 31, amateur astronomer Eliot Herman spotted another outburst as 12P became almost 100 times brighter than usual, Spaceweather.com reported.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"On Halloween, the devil burst forth again with a large outburst that continued into the next day," Herman told Spaceweather.com. Subsequent observations showed that its coma expanded significantly and regrew its horns, although they were not as distinct as they were in previous eruptions, he added.

Approaching Earth

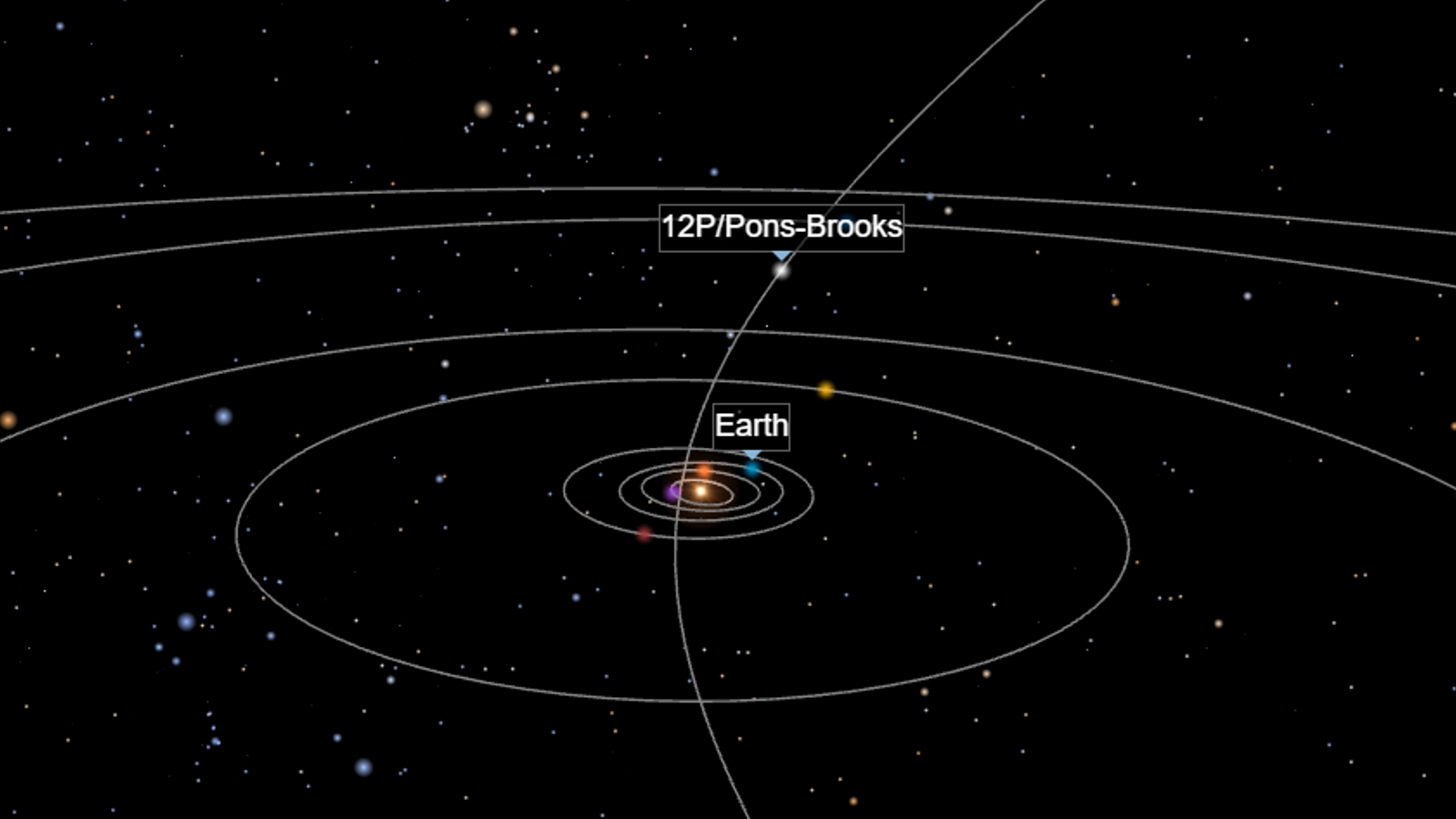

12P has an elliptical orbit, which means it gets pulled close to the sun before being slingshotted back into the outer solar system, where it slowly drifts before eventually falling back toward the inner solar system. This trajectory is very similar to the orbit of the green comet Nishimura, which pulled off a similar slingshot maneuver around the sun in September.

It takes around 71 years for 12P to complete one full trip around the sun, most of which is spent hidden in the outer solar system. As a result, astronomers can only clearly see the comet as it begins to make its closest approach to the sun, which is happening now.

Related: Bright new comet discovered zooming toward the sun could outshine the stars next year

12P will reach its closest point to the sun, or perihelion, on April 24, 2024, when it will reach a minimum distance of 72.5 million miles (116.7 million km), which is closer to the sun than Earth but further away than Venus, according to TheSkyLive.com.

After slingshotting around the sun, the comet will reach its closest point to Earth on June 2 next year when it will pass by at a distance of 144.1 million miles (231.9 million km) — or around 1.5 times further away from Earth than the sun — on its way back out into the shadows of the outer solar system. It will remain there until 2094, according to TheSkyLive.com.

Comets appear brighter in the night sky as they get closer to the sun because their comas reflect more sunlight. This means there is a decent chance it will be visible with the naked eye in late May or early June as it flies by Earth.

As 12P gets closer to the sun, it may also regularly show off its devilish horns as it soaks up more solar radiation that boils its icy guts and makes eruptions more likely.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus