'Potentially hazardous' 600-foot asteroid detected near Earth after a year of hiding in plain sight

A skyscraper-size asteroid was revealed in year-old telescope data thanks to a new algorithm that could rock the way near-Earth objects are discovered.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Astronomers have discovered a massive, skyscraper-size asteroid hiding in plain sight near Earth, thanks to a new algorithm designed to hunt the biggest, deadliest space rocks.

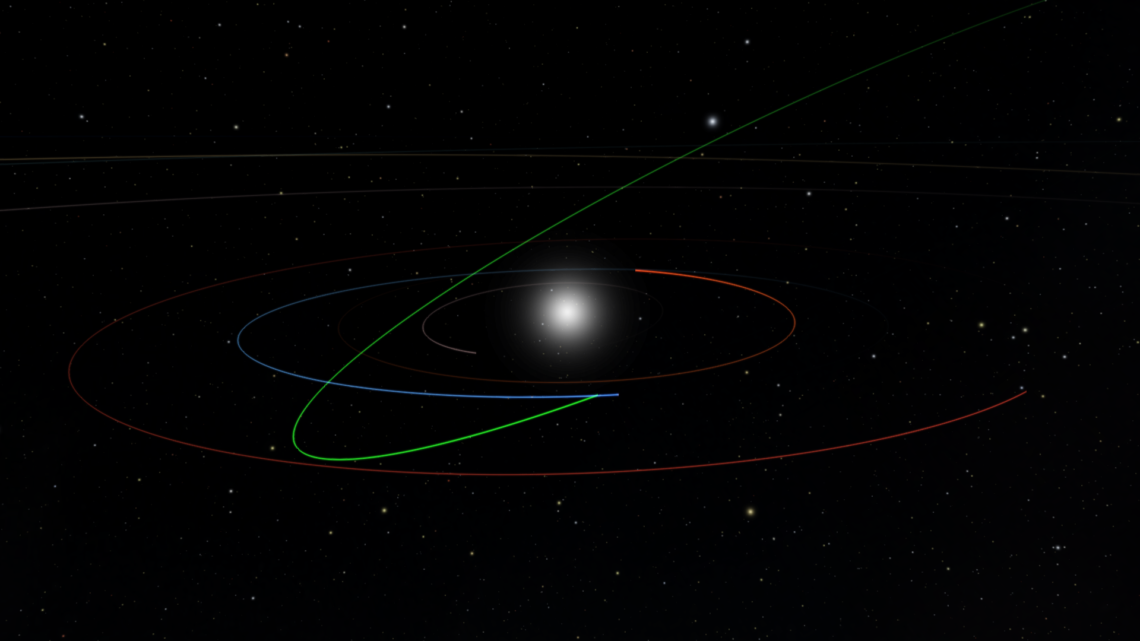

The 600-foot-wide (180 meters) asteroid — now officially named 2022 SF289 — is large enough and orbits closely enough to Earth to be considered a potentially hazardous asteroid (PHA) — one of roughly 2,300 similarly classed objects that could cause widespread destruction on Earth should a direct collision occur. (Luckily, there is no risk of collision with this rock at any point in the foreseeable future.)

The asteroid made a close approach to Earth in September 2022, when it flew within about 4.5 million miles (7.2 million kilometers) of our planet, according to NASA. Yet astronomers around the world failed to detect the asteroid in telescope data at any point before, during or after the approach, as the large rock was obscured by Milky Way starlight.

Now, researchers have finally revealed the space rock's existence while testing out a new algorithm that's tailor-made to detect large asteroids from small fragments of data. The detection of a PHA that's too sneaky for traditional methods to spot represents a huge vindication for the algorithm, which will soon be used to comb over data gathered by the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, a cutting-edge telescope in the Chilean mountains scheduled to begin asteroid-hunting operations in early 2025.

"This is just a small taste of what to expect with the Rubin Observatory in less than two years, when [the algorithm] HelioLinc3D will be discovering an object like this every night," Mario Jurić, director of the Institute for Data Intensive Research in Astrophysics and Cosmology at the University of Washington and the team leader behind the new algorithm, said in a statement.

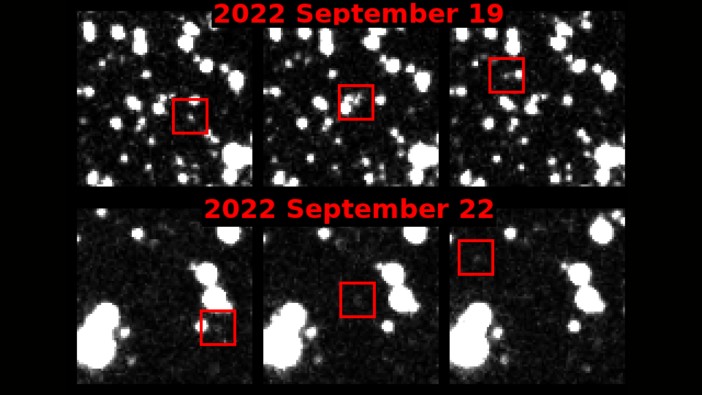

To ensnare their first asteroid, the scientists put their algorithm to the test on archival data from the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) survey in Hawaii, which takes at least four images of the same spot of the sky every night. The search revealed something that ATLAS had missed: a large asteroid, visible in three separate sky images taken on Sept. 19, 2022, and the three following nights.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

ATLAS requires that an object appear in four separate images taken on a single night before that object can be considered an asteroid. Because 2022 SF289 did not meet that criteria, the world never knew about its close brush with our planet.

The new HelioLinc3D algorithm, meanwhile, is designed to cobble together asteroid detections from much less data. The Rubin Observatory, for which the algorithm was designed, will scan the sky only twice a night, albeit in much higher detail than most modern observatories, according to the researchers.

The team is confident that 2022 SF289 is just the tip of the asteroid-detecting iceberg for Rubin and the new algorithm. There may be thousands of hidden PHAs circling our planet, awaiting detection — and the team is ready to hunt them down.

"From HelioLinc3D to AI-assisted codes, the next decade of discovery will be a story of advancement in algorithms as much as in new, large, telescopes," Juric said.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus