Scientists are finally learning what's inside mysterious 'halo' barrels submerged off Los Angeles

At first thought to hold the pesticide DDT, some mysterious barrels dumped in the deep sea near Los Angeles actually contain caustic alkaline waste that stops most life from living nearby.

Thousands of barrels of industrial waste litter the ocean floor off Los Angeles and have been there for decades — but scientists still don't fully understand what chemicals this junkyard is leaking into the environment.

Now, research has revealed that some of the chemicals leaking from the barrel graveyard have been identified as strongly alkaline, the chemical opposite of acidic — and they are still concentrated enough to stop most life living nearby.

Between the 1930s and early 1970s, radioactive waste, refinery waste, chemical waste, oil-drilling waste and military explosives were dropped into 14 dump sites in deep water off the coast of Southern California, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

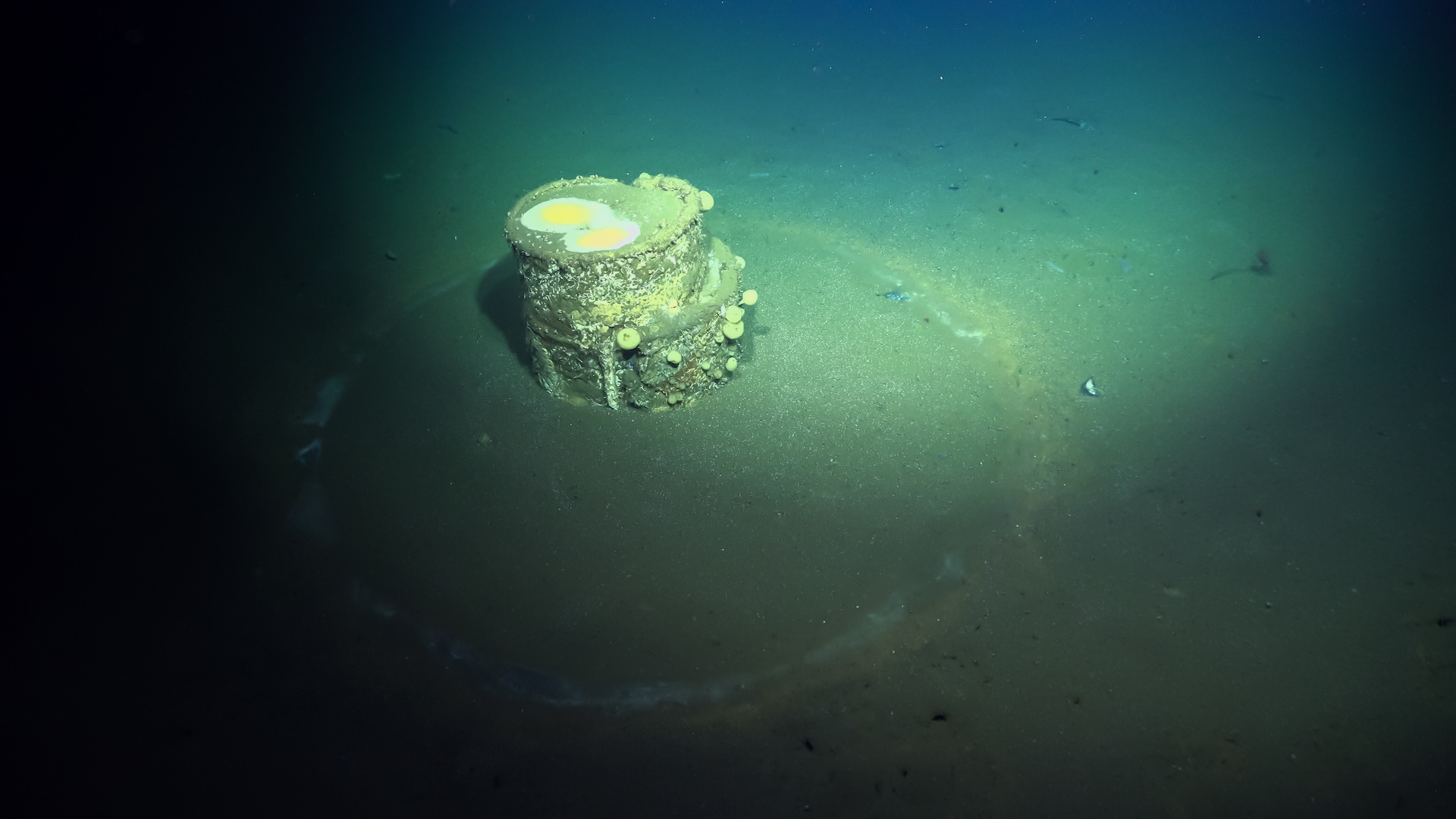

This huge underground junkyard came into the public consciousness in 2020, when an LA Times article revealed that deep-sea robot surveys had discovered dozens of barrels littered over the sea floor. Then, in 2021 and 2023, follow-up surveys by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California identified some 27,000 shapes that seemed to be barrels and more than 100,000 total debris objects on the seafloor. Some suspected that the barrels, many of which were encircled by whitish haloes in the sediment, contained the now-banned pesticide DDT, because the area is heavily contaminated with it.

But to this day, the total number of barrels on the seafloor — and what most of them contain — remains unknown.

Now, Johanna Gutleben, a microbiologist at the Scripps Institution, and her colleagues have revealed the results of sediment samples taken near five barrels using a remotely operated vehicle in 2021. They found that levels of DDT contamination didn't increase closer to the barrels, so they say the drums didn't contain that chemical.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Three of the barrels they checked had white halos around them and all the samples from near these barrels had an extremely high pH (around 12) and very few microbes living there, so the team say the barrels contained caustic alkaline waste, which can damage organic matter and leach out high concentrations of potentially toxic metals.

The team's study was published Tuesday (Sept. 9) in the journal PNAS Nexus.

"Up to this point we have mostly been looking for DDT. Nobody was thinking about alkaline waste before this and we may have to start looking for other things as well," Gutleben said in a statement.

The sampling didn't identify which specific chemicals were in the barrels, but notably, DDT manufacturing produces alkaline waste, as does oil refining.

"One of the main waste streams from DDT production was acid and they didn't put that into barrels," said Gutleben. "It makes you wonder: What was worse than DDT acid waste to deserve being put into barrels?"

As the researchers found very limited levels of microbial DNA near the barrels, they say the alkali waste likely transformed parts of the seafloor into extreme environments where most life can't survive. They did find traces of some specialized bacteria, though — species from families adapted to alkaline environments, like deep-sea hydrothermal vents and alkaline hot springs.

The team also discovered how the weird haloes form. When the alkaline waste leaks from the barrels, it reacts with magnesium in the water and creates a mineral form of magnesium hydroxide, called brucite, forming a concrete-like crust. The brucite then slowly dissolves, keeping the pH in the sediments high while leading to reactions in surrounding seawater. This results in the formation of calcium carbonate, which settles as white dust around the barrels.

Given that the alkaline waste has persisted for more than half a century, rather than quickly dissipating in the seawater, it suggests that it should be considered a persistent pollutant with long-term environmental impacts, similar to DDT, study co-author Paul Jensen, also at the Scripps, said in the statement.

"It's shocking that 50-plus years later you're still seeing these effects," he said.

The researchers suggest using the white halos to identify which barrels contain alkaline waste so the overall extent of contamination can be assessed. Jensen said roughly one-third of the barrels that have been seen so far have halos, but it's unclear if this ratio will hold as more barrels are uncovered.

Chris Simms is a freelance journalist who previously worked at New Scientist for more than 10 years, in roles including chief subeditor and assistant news editor. He was also a senior subeditor at Nature and has a degree in zoology from Queen Mary University of London. In recent years, he has written numerous articles for New Scientist and in 2018 was shortlisted for Best Newcomer at the Association of British Science Writers awards.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus