Murder hornets and monkey cannibals: 10 times nature freaked us out in 2020

Some of this year's top science stories were truly the stuff of nightmares.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Stomach-bursting eels! Tongue-devouring sea lice! Nature can be the best at being the absolute worst, and 2020 gifted us with a petrifying parade of shudder-inducing science. From baby-eating cannibal monkeys to vampire parasites, here are 10 times this year when nature proved that it was positively horrific. You're welcome.

Bone-eaters

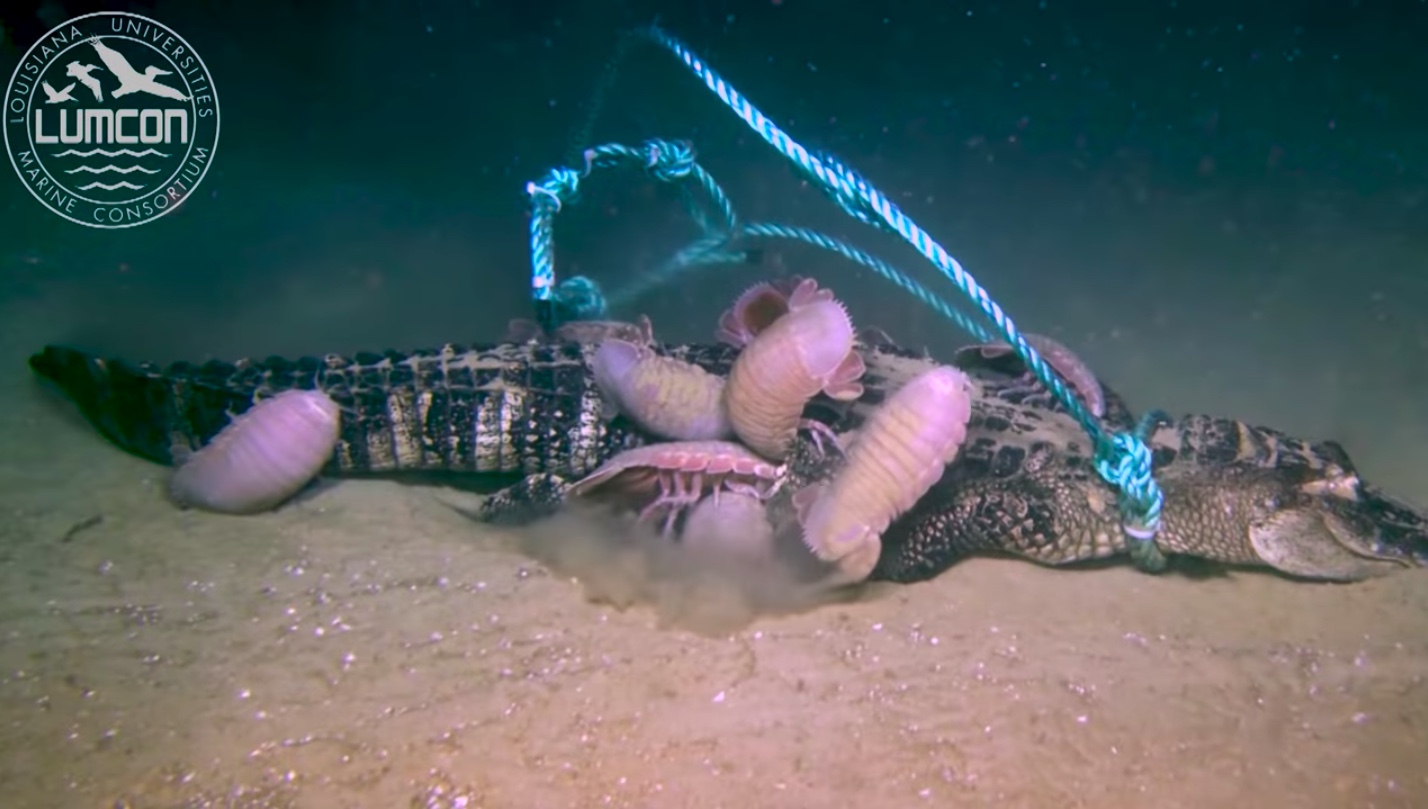

Scavengers in the deep ocean eagerly devour alligator corpses — some pick the bones clean, while others munch on the bones, scientists recently discovered. Researchers sent three dead freshwater gators to the sea bottom in the Gulf of Mexico, depositing them at a depth of 6,600 feet (2 kilometers) to see how marine creatures might respond to a type of food that they wouldn't usually find on the sea floor. Turns out those deep sea critters aren't picky.

Footage captured by a camera on a diving robot showed that enormous pink isopods (crustaceans that resemble terrestrial woodlice or pill bugs, at a much larger scale) swarmed over the alligators, stripping flesh from the skeletons. After all the meat was gone, the bones were covered in a brown fuzz, and DNA analysis revealed that this coating was a previously unknown species of bone-eating worm.

Read more: New bone-eating life form discovered in bizarre alligator-corpse study

Toxic toupeé

What looks like a walking wig, except with "hairs" that are really venom-spurting spines? It's the caterpillar of the southern flannel moth (Megalopyge opercularis), and these toxic "toupeés" appeared in Virginia in record numbers this year. As climate change warms the planet, animals shift their ranges in response, and global warming could explain why the caterpillars were more numerous in Virginia in 2020 than they usually are.

Read more: Weird venomous caterpillars that look like walking toupées are invading Virginia

Hornets from hell

Asian giant hornets (Vespa mandarinia), the biggest hornets in the world, are gaining a foothold in the United States for the first time; the size of their stingers and the potency of their venom makes the insects uniquely dangerous to people, but the hornets pose a much greater threat to North American honeybees.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers in Washington first found individual hornets — also known as murder hornets — in April. The first murder hornet nest was found and destroyed in October, and that nest may have held as many as 200 new queens. Hornet queens can grow to be 2 inches (5 centimeters) in length, and female workers and males measure about 1 to 1.5 inches (3.5 to 3.9 cm), and they are known for mobbing honey bees' hives, killing or driving off all the bees, and then moving in and taking over the abandoned nurseries, feeding the bee larvae to their hornet babies.

Read more: Monstrous 'murder hornets' have reached the US

'Vampire' parasite

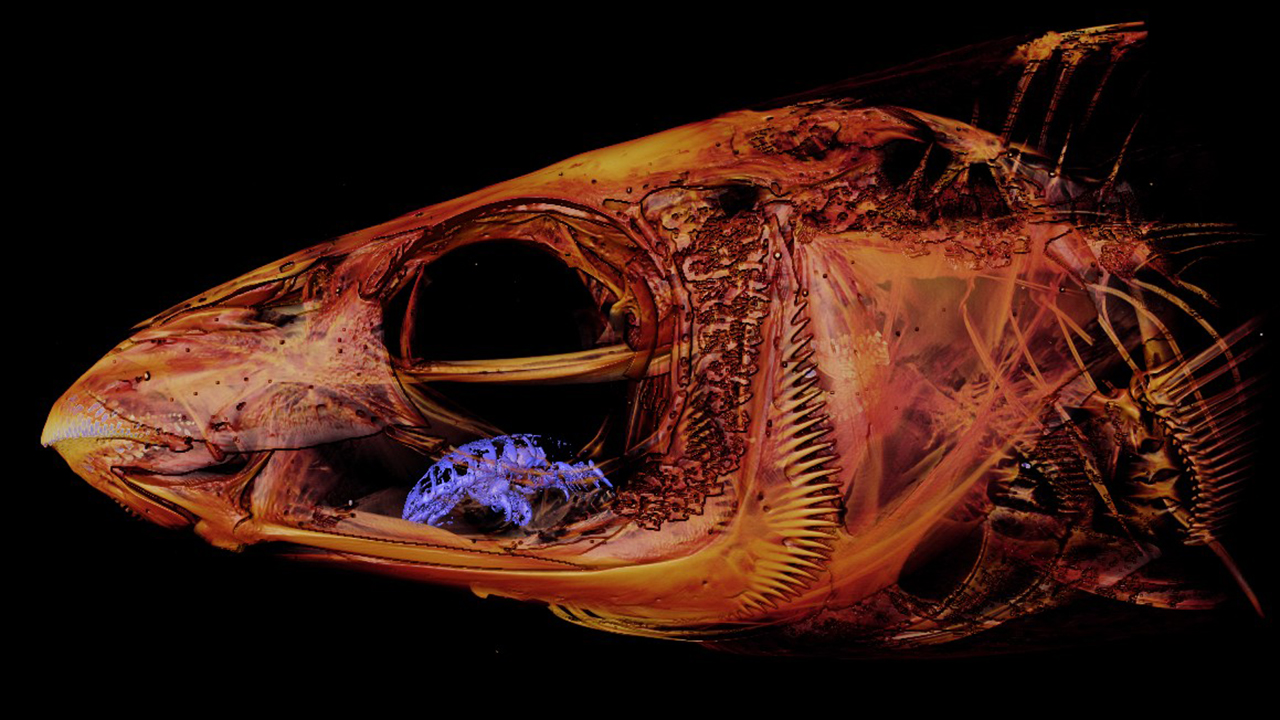

It was just another Monday for biologist Kory Evans, an assistant professor in the Department of BioSciences at Rice University in Houston, Texas, when he X-rayed a fish's head in 3D and discovered that its tongue had been replaced by a parasite.

Actually, his Mondays "aren't usually this eventful," Evans wrote on Twitter.

Instead of a normal tongue, the fish had a tongue-eating isopod squatting inside its mouth. These so-called vampire crustaceans enter a fish's mouth as larvae, attach to the tongue by tightly gripping it with their legs, and feed on blood that they siphon from the organ. Eventually, the tongue withers and falls off, and the now-fully-grown isopod serves as a functional tongue for the fish.

Read more: Meet the 'vampire' parasite that masquerades as a living tongue

Gone fishing

A sizable semi-aquatic spider went fishing and snagged a man's pet goldfish, named Cleo, out of a backyard pond in Barberton, South Africa. The man arrived home just in time to capture photos of the heinous act, as the arachnid — a nursery web spider, also known as a fishing spider — dragged poor Cleo from the water. Cleo was likely already dead at this point, killed by a venomous bite. And though she was about twice the size of her attacker, these spiders can easily subdue prey up to five times their size, scientists reported in 2014.

Read more: A man caught a spider eating his pet goldfish and, well, it's terrifying

Embryo infection

In case you're wondering what it might take to shock a scientist; researchers in Sweden were dissecting developing lizard embryos, when they were extremely surprised to see "something moving" in the brains of the embryonic lizards. The scientists found that nematodes, a type of parasitic worm, had infested the ovaries in the embryos' mothers. From there, the parasites were able to pass into the embryos' brains before the hard shell of an egg could form around them, so the baby lizards were already parasitized when they hatched.

Read more: 'Shocked' scientists find brain parasites in baby lizards still in shells

Loon vs. eagle

When a dead eagle was found with a puncture in its chest, experts determined that the murder weapon was likely the "dagger-like bill" of a loon. A game warden in Maine found the eagle's body near a lake and brought it to a nearby veterinarian, thinking that the bird had been shot. A radiograph showed that there was no bullet in the body, but there was a deep wound that was similar in size to a loon's beak. The eagle was found with a dead loon chick nearby, and scientists suspect that a loon parent tried to defend its baby from the attacking eagle, landing a lethal jab that pierced the predator's heart.

Read more: Loon stabs bald eagle to death

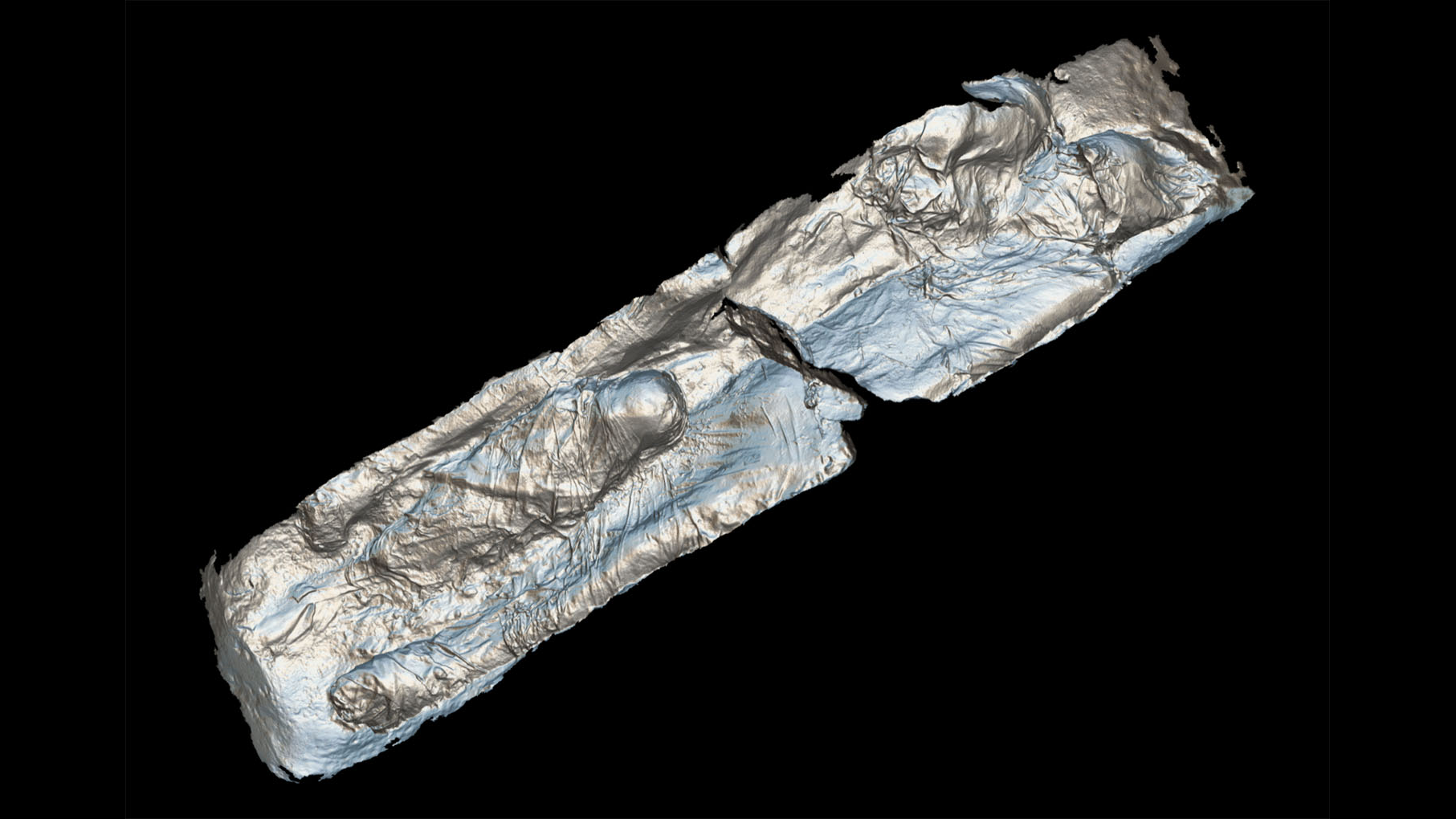

Stomach-burster: fish edition

When fish gulp down sinuous snake eels, the eels can stage a desperate escape by using a hardened, bony tail tip to punch a hole in the predator's gut. But that strategy might leave a swallowed eel in an even worse predicament: once it slips out of the stomach, it's still trapped inside the bigger fish's gut cavity. Scientists recently documented grisly evidence of such failed escapes, finding mummified snake eels inside the bodies of more than a dozen predatory Protonibea diacanthus fish in waters around coastal Australia.

Read more: Snake eels stage stomach-bursting escape after being eaten (and then things get really nasty)

Stomach-burster: bird edition

As if one gruesome stomach-burster story wasn't enough, 2020 decided that we needed another. In this case, the predator was a heron in Delaware that swallowed an American eel (Anguilla rostrata). But the eel had other plans, and photographer Sam Davis of Maryland captured the incredible sight of the heron in flight, with the eel emerging headfirst from the bird's stomach, bursting all the way out of the bird's body to dangle in midair under the heron's outstretched neck.

"I could see the eel, you could see its eyes," Davis told Live Science.

Read more: Alien-like photo shows eel dangling out of heron's stomach in midair

Capuchin cannibals

Scientists reported the first known case of infant cannibalism practiced by white-faced capuchin monkeys (Cebus imitator), in a population that researchers have observed for nearly four decades in Costa Rica's Santa Rosa National Park. After a 10-day-old baby monkey fell from a tree, possibly killed by an older male, two monkeys from the troop partly consumed the dead infant while its mother watched nearby. Cannibalism in monkeys from Central and South America is exceptionally rare, and typically happens when infants are killed by unrelated monkeys, with the baby's relatives eating the remains.

Read more: Adorable monkeys caught committing grisly act of cannibalism

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus