High-speed video shows every second of a praying mantis's lethal strike

How fast they attack depends on the speed of their prey

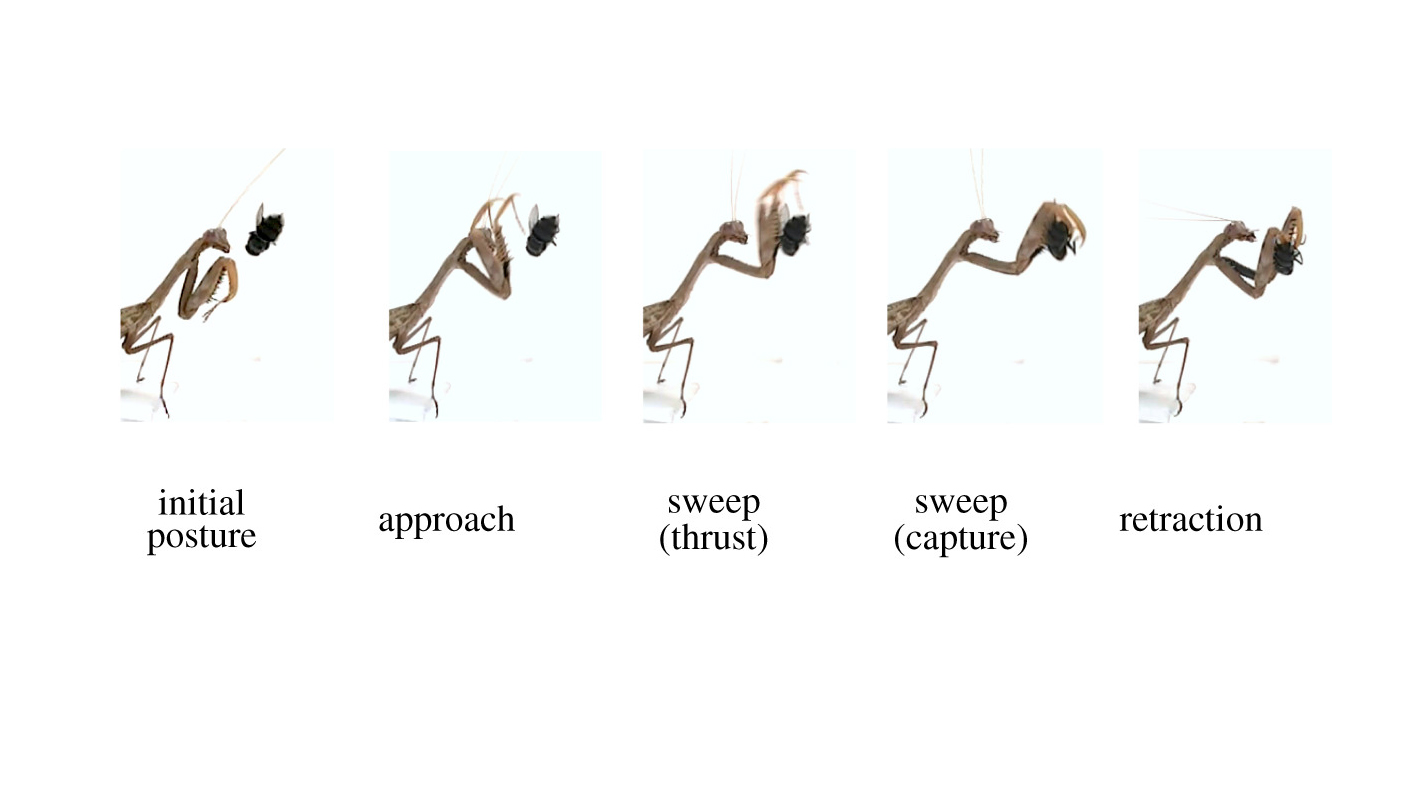

New slow-motion video shows how praying mantises snatch their prey with lightning-fast, deadly precision.

Though these strikes are completed in microseconds, the long-armed predators calibrate their attacks even more quickly than that, adjusting to prey's speed and movements; praying mantises can even halt mistimed attacks mid-strike, scientists reported in a new study.

Related: Lunch on the wing: Mantises snack on birds (photos)

Mantises are ambush predators; rather than stalking or chasing their prey, they select a perch and then wait, motionless, their spike-studded arms folded and ready. When an unsuspecting victim wanders too close, the mantis lunges and grabs, holding tight to the prey's wriggling body. The mantis then begins to feed on its living victim almost immediately.

This type of sit-and-wait approach was long thought to be mostly one-size-fits-all, with predators using the same technique over and over again, said lead study author Sergio Rossoni, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Zoology at the University of Cambridge's Clare College, in England.

"This is because a lot of famous sit-and-wait predators use attacks, which rely on a loaded spring (like a jack-in-the-box toy), such as the projectile tongue of frogs, or the loaded punch of mantis shrimps," Rossoni told Live Science in an email.

"The assumption was that a spring needs to be loaded with a set force in order to spring back, leaving little room for variability," he explained.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But Rossoni and his co-author Jeremy Niven, a senior lecturer at the University of Sussex in England, suspected that mantises' ambush attacks could be more flexible. The scientists put that to the test by observing and documenting the hunting habits of Madagascan marbled praying mantids (Polyspilota aeruginosa), creating enclosed "arenas" for their mantises; offering them small insects or tiny beads as attack targets; and filming the mantis strikes at 200 frames per second.

Huge variation

The researchers then reviewed and analyzed the slow-motion footage. They found that the speed of the strikes varied greatly, with some taking just 60 milliseconds (a millisecond is one-thousandth of a second), and some lasting nearly five times as long, up to 290 milliseconds. The speed of the mantises' strikes changed in response to the speed of the moving prey, according to the study.

Even more surprising was that the mantises would sometimes "pause" mid-strike, either to correct an attack if they moved too soon, or to abandon an ill-timed move before they caught their prey — a behavior that had never been described before in these big insects, Rossoni said.

This suggests that mantids monitor the timing of their attacks and calculate the speed and trajectory of their prey to pinpoint precisely when they should snatch it, the researchers found. However, that doesn't mean that the insects are adding up numbers in their tiny heads, Rossoni said.

"I'm not suggesting that they can do maths, just like humans do not consciously calculate the speed of a moving ball when trying to catch it. But the mantid's nervous system is somehow capable of transforming visual information about prey into a well-timed sequence of motor output," he explained.

"For a brain as small as an insect's, that's quite formidable! So, we would like to understand how the mantid's nervous system is capable of this, with future research," Rossoni said.

The findings were published online May 13 in the journal Biology Letters.

- Image gallery: Bug's eye camera

- Gallery: Out-of-this-world images of insects

- No creepy crawlies here: Gallery of the cutest bugs

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'How It Works' 'All About Space' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus