When will a COVID-19 vaccine be ready?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, recently said that a COVID-19 could take 12 to 18 months to develop, test and approve for public use. But new vaccines typically take years to earn approval — can we really expect a coronavirus vaccine to be ready by summer 2021?

Experts told Live Science that, for any other vaccine, the timeline would be unrealistic. But given the current pressure to stave off the pandemic, a COVID-19 vaccine could be ready sooner, as long as scientists and regulatory agencies prove willing to take a few shortcuts.

Here's why it probably can't be developed any sooner than 12 to 18 months.

Testing many options

More than 60 candidate vaccines are now in development, worldwide, and several have entered early clinical trials in human volunteers, according to the World Health Organization.

Related: Treatments for COVID-19: Drugs being tested against the coronavirus

Some groups aim to provoke an immune response in vaccinated people by introducing a weakened or dead SARS-CoV-2 virus, or pieces of the virus, into their bodies. The vaccines for measles, influenza, hepatitis B and the vaccinia virus, which causes smallpox, use these approaches, according to the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Although tried-and-tested, using this approach to develop these conventional vaccines was labor-intensive, requiring scientists to isolate, culture and modify live viruses in the lab.

That initial process of just creating a vaccine can take 3 to 6 months, "if you have a good animal model to test your product," Raul Andino-Pavlovsky, a professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of California, San Francisco, told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Given the current time crunch, some groups have opted for faster, if less conventional, approaches.

The first COVID-19 vaccine to enter clinical trials in the United States, for example, uses a genetic molecule called mRNA as its base. Scientists generate the mRNA in the lab and, rather than directly injecting SARS-CoV-2 into patients, instead introduce this mRNA. By design, the vaccine should prompt human cells to build proteins found on the virus' surface and thus trigger a protective immune response against the coronavirus. Other groups aim to use related genetic material, including RNA and DNA, to build similar vaccines that would interfere with an earlier step in the protein construction process.

Related: 10 deadly diseases that hopped across species

But there's one big hurdle for mRNA vaccines. We can't be sure they will work.

As of yet, no vaccine built from a germs' genetic material has ever earned approval, Bert Jacobs, a professor of virology at Arizona State University and member of the ASU Biodesign Institute's Center for Immunotherapy, Vaccines and Virotherapy, told Live Science. Despite the technology having existed for almost 30 years, RNA and DNA vaccines have not yet matched the protective power of existing vaccines, National Geographic reported.

Assuming these unconventional COVID-19 vaccines pass initial safety tests, "will there be efficacy?" Jacobs said. "The animal models suggest it, but we'll have to wait and see."

"Because of the emergency here, people are going to try many different solutions in parallel," Andino-Pavlovsky said. The key to trialing many vaccine candidates at once will be to share data openly between research groups, in order to identify promising products as soon as possible, he said.

Metrics used to measure efficacy — whether a vaccine sparks an adequate response from a person’s immune system — in animal studies and early clinical trials will also need to be clearly defined, he added. In other words, researchers should be able to use these early studies to determine which vaccines to move forward with, which to modify and which to abandon. That whole process — from lab dish to animal studies — can take 3 to 6 months, Andino-Pavlovsky said.

Challenges in vaccine development

Designing a vaccine that grants immunity and causes minimal side effects is no simple task. A coronavirus vaccine, in particular, poses its own unique challenges. Although scientists did create candidate vaccines for the coronaviruses SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, these did not exit clinical trials or enter public use, partly because of lack of resources, Live Science previously reported.

"One of the things you have to be careful of when you're dealing with a coronavirus is the possibility of enhancement," Fauci said in an interview with the journal JAMA on April 8. Some vaccines cause a dangerous phenomenon known as antibody dependent enhancement (ADE), which paradoxically leaves the body more vulnerable to severe illness after inoculation.

Related: Could a 100-year-old vaccine protect against COVID-19?

Candidate vaccines for dengue virus, for example, have generated low levels of antibodies that guide the virus to vulnerable cells, rather than destroying the pathogen on sight, Stat News reported. Coronavirus vaccines for animal diseases and the human illness SARS triggered similar effects in animals, so there's some concern that a candidate vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 might do the same, according to an opinion piece published March 16 in the journal Nature. Scientists should watch for signs of ADE in all upcoming COVID-19 vaccine trials, Fauci said. Determining whether enhancement is occurring could happen during initial animal studies, but "it is still unclear how we will look for ADE," Jacobs said.

"Once there is a good animal model which gives symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection, we can ask if vaccination decreases or enhances pathogenesis," he said. "These may be longer term studies that could take several months." The ADE studies could be done in parallel with other animal trials to save time, Andino-Pavlovsky added.

There's another challenge too.

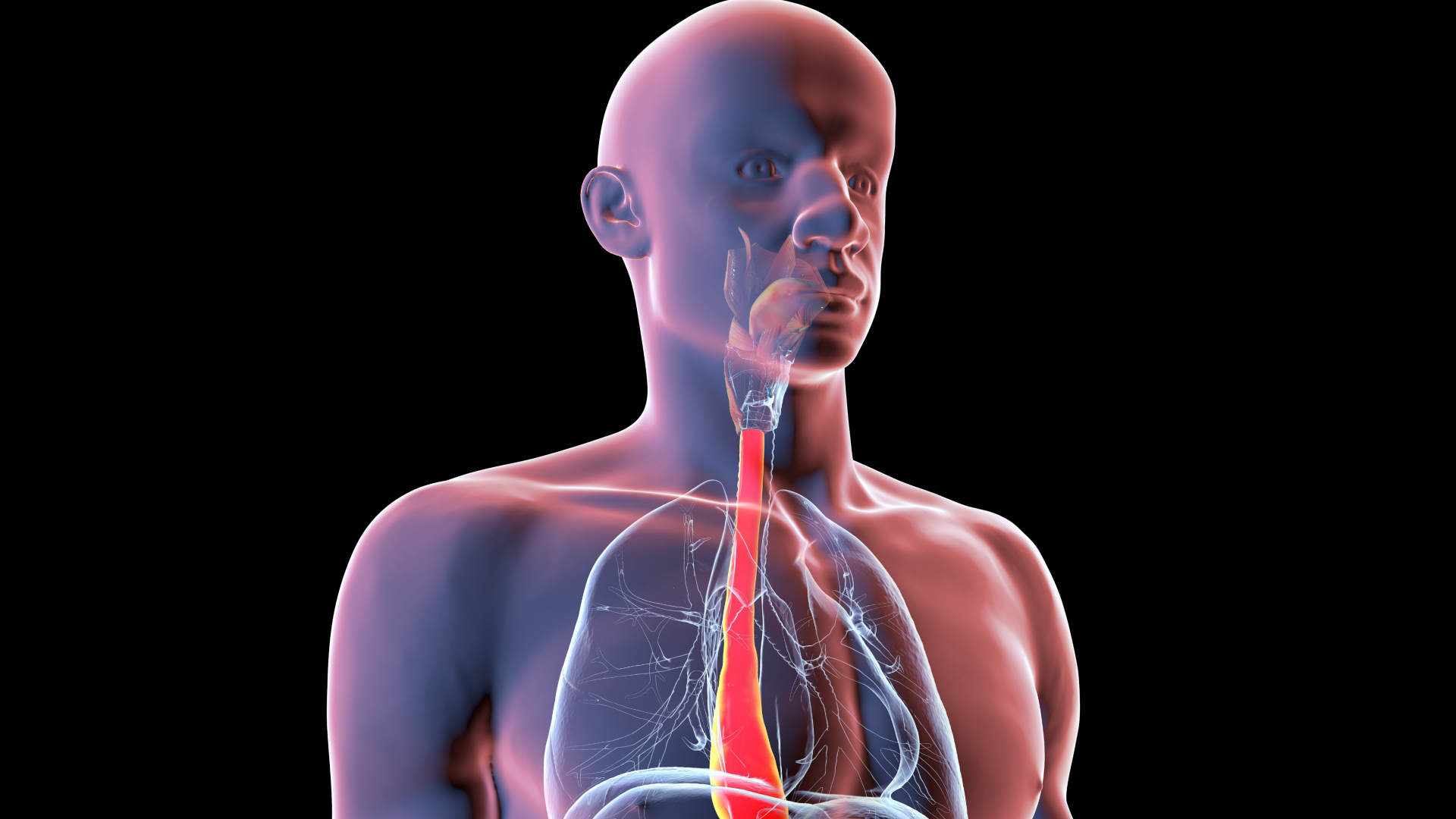

A successful coronavirus vaccine will snuff the spread of SARS-CoV-2 by reducing the number of new people infected, Andino-Pavlovsky said. COVID-19 infections typically take hold in so-called mucosal tissues that line the upper respiratory tract, and to effectively prevent viral spread, "you need to have immunity at the site of infection, in the nose, in the upper respiratory tract," he said.

These initial hotspots of infection are easily permeated by infectious pathogens. A specialized fleet of immune cells, separate from those that patrol tissues throughout the body, are responsible for protecting these vulnerable tissues. The immune cells that protect mucosal tissue are generated by cells called lymphocytes that remain nearby, according to the textbook “Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease” (Garland Science, 2001).

"It's like your local police department," Andino-Pavlovsky told Live Science. But not all vaccines prompt a strong response from the mucosal immune system, he said. The seasonal influenza vaccine, for example, does not reliably trigger a mucosal immune response in all patients, which partly explains why some people still catch the respiratory disease after being vaccinated, he said.

Even if a COVID-19 vaccine can jumpstart the necessary immune response, researchers aren’t sure how long that immunity might last, Jacobs added. While research suggests that the coronavirus doesn't mutate quickly, "we have seasonal coronaviruses that come, year in [and] year out, and they don't change much year to year," he said. Despite hardly changing form, the four coronaviruses that cause the common cold keep infecting people — so why haven't we built up immunity?

Perhaps, there’s something odd about the virus itself, specifically in its antigens, viral proteins that can be recognized by the immune system, and that causes immunity to wear off. Alternatively, coronaviruses may somehow fiddle with the immune system itself, and that could explain the drop-off in immunity over time, Andino-Pavlovsky said. To ensure a vaccine can grant long-term immunity against SARS-CoV-2, scientists will have to address these questions. In the short term, they'll have to design experiments to challenge the immune system after vaccination and test its resilience through time, Jacobs said.

In a mouse model, such studies could take "at least a couple of months," he said. Scientists cannot conduct an equivalent experiment in humans, but can instead compare natural infection rates in vaccinated people to those of unvaccinated people in a long-term study.

"When you have the luxury, you look at this for five years, 10 years to see what happens," Andino-Pavlovsky added.

Shortcuts to approval

Unlike an antiviral treatment for COVID-19 that can be given to patients already infected with the virus, a vaccine must be tested in diverse populations of healthy people.

"Because you give it to healthy people, there's an enormous pressure to make sure it's absolutely safe," Andino-Pavlovsky said. What's more, the vaccine must work well for people of many ages, including the elderly, whose weakened immune systems place them at heightened risk of serious COVID-19 infection.

"Initially, safety studies will be done in small numbers of people," likely fewer than 100, Jacobs said. A vaccine may be approved based on these small studies, which can take place over a few months, and then continually monitored as larger populations become vaccinated, he added. "That's just my guess."

Related: COVID-19 is now the leading cause of death in the United States

A future vaccine may require an additional ingredient, called an adjuvant, that rallies the aged immune system into action, like that found in the shingles vaccine, Jacobs said.

While some existing drugs, whose safety risks doctors understand, may be repurposed as COVID-19 treatments, equivalent data does not exist for a vaccine because no coronavirus vaccine has ever entered widespread use. Jacobs said he and his team aim to exploit a potential loophole to develop a powerful vaccine, fast. "We use surrogate live attenuated vaccines, where we put parts of SARS-CoV-2 into vaccinia virus [which guards against smallpox], and this can be done initially within a month," Jacobs said. In general, many vaccine developers are starting from scratch.

Despite the many challenges ahead, certain shortcuts could allow scientists to bring a COVID-19 vaccine faster than anticipated.

First, partnering with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and other regulatory bodies can help scientists leap the logistical hurdles associated with clinical trials, such as recruiting healthy volunteers, Andino-Pavlovsky said. "It can save six months, doing that," he said.

Any potential vaccine will need to pass a safety trial, known as a Phase 1 trial, which also helps determine the needed dose. The next step is a larger trial in 100 to 300 people, called a Phase 2, which looks for some biological activity, but can't say for sure if the drug is effective.

If a vaccine candidate prompts a promising immune response in Phase 2 clinical trials, after passing safety tests in Phase 1, it's possible that the FDA could approve such a vaccine for emergency use "before the 18-month period that I said," Fauci said in the JAMA interview.

"If you get neutralizing antibodies," which latch onto specific structures on the virus and neutralize it, "I think you can keep moving forward on it," Jacobs said. Normally, a vaccine would then enter Phase 3 clinical trials, which include hundreds to thousands of people.

So adding up these steps, each of which will likely take 3 to 6 months, it's very unlikely we would be able to find a vaccine that is safe and effective in less than 12 months — even if many of these steps could be done in parallel.

Then comes the issue of manufacturing billions and billions of doses of a new vaccine whose ingredients we don't yet know. Bill Gates has said that the Gates Foundation will fund the construction of factories for seven coronavirus vaccine candidates, equipping the sites to produce a wide variety of vaccine types, Business Insider reported.

"Even though we'll end up picking at most two of them, we're going to fund factories for all seven, just so that we don't waste time in serially saying, 'OK, which vaccine works?' and then building the factory," Gates said.

Even if a fairly promising vaccine surfaces by 2021, and can be mass-produced, the search won't end there. "Especially with trying to get something out this quickly, we may not get the best vaccine out there right away," Jacobs said. Ideally, an initial vaccine will grant immunity for at least one to two years, but should that immunity wane, a longer lasting vaccine may have to be deployed. Historically, so-called live attenuated vaccines that contain a weakened virus tend to perform most reliably over extended periods of time, Andino-Pavlovsky said.

"That may be what we need in the long run," he said. And research into coronavirus immunity should continue, regardless, "not only for COVID-19, but for the next coronavirus that comes."

- Going viral: 6 new findings about viruses

- The 12 deadliest viruses on Earth

- Top 10 mysterious diseases

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'How It Works' 'All About Space' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus