Unusually cold 'Blue Blob' is slowing the rapid melting of Iceland's glaciers, but not for long

The mysterious patch of the North Atlantic Ocean is fighting back the effects of climate change.

The "Blue Blob," an unusually cold patch of water in the Arctic, has halved the rate at which Iceland's glaciers are melting, but a new study reveals that the effects of climate change will catch up to the massive ice chunks if temperatures are not kept in check.

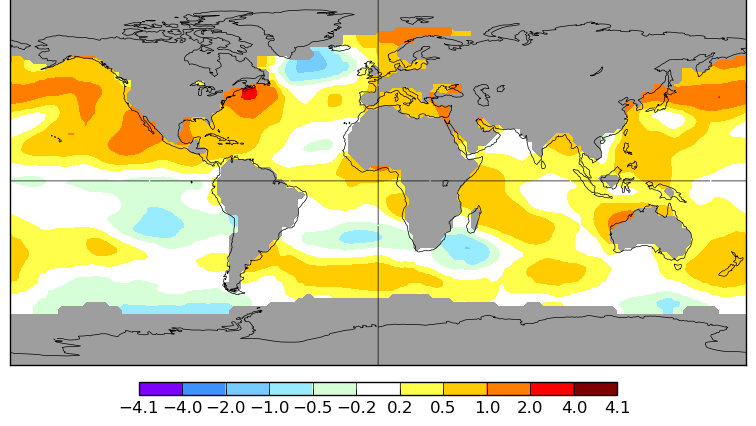

The Blue Blob is an undefined area of the North Atlantic Ocean located south of Iceland and Greenland. At its peak coldness, in 2015, the Blue Blob was 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit (1.4 degrees Celsius) colder than the surrounding waters. Before the emergence of the Blue Blob, Iceland's glaciers were losing a staggering 11 gigatons of ice every year due to melting. But since the cool patch emerged in 2011, that rate has more than halved to a slightly less worrying 5 gigatons a year — even though the rest of the Arctic is warming four times faster than anywhere else on Earth, according to a statement from the American Geophysical Union.

In the new study, published online Jan. 24 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, researchers used climate models to predict how long the Blue Blob could continue to slow the glaciers' rampant melting. They found that the rising temperatures will overcome the cooling effect and match rapid melting rates seen in nearby Greenland and the Norwegian archipelago Svalbard by the mid-2050s.

Related: 10 things you need to know about Arctic sea ice

Researchers say this finding is important because it improves our understanding of trends throughout the Arctic. "It's crucial to have an idea of the possible feedbacks in the Arctic, because it's a region that is changing so fast," lead author Brice Noël, a climate scientist at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, said in the statement. "It's important to know what we can expect in a future warmer climate."

Iceland currently hosts four major ice caps each larger than 193 square miles (500 square kilometers), seven smaller ice masses each larger than 4 square miles (10 square km) and around 250 other glaciers smaller than 4 square miles. In total, the volume of ice on the island nation is estimated to be around 816 cubic miles (3,400 cubic km), which would be enough to raise global sea levels by 0.35 inches (9 millimeters) if it completely melted, the researchers wrote in the paper. This is the equivalent to around three times the current global sea rise we are experiencing every year, according to the Smithsonian Institute.

Almost all of Iceland's glaciers terminate on land, meaning they do not come into contact with the sea. Therefore, the rate at which they melt is dependent on their surface mass balance, which is the difference between ice gained from winter snowfall and ice lost from meltwater runoff in the summer. However, the Blue Blob is so cold that it decreases the temperature of the air that flows over it, which then cools the atmosphere surrounding Iceland and, in turn, reduces the surface mass balance of its ice masses, meaning less ice is lost.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Using the latest climate prediction models and local atmospheric temperature readings dating back to the 1990s, the team pinpointed when rising temperatures caused by climate change would outweigh the influence of the Blue Blob on Iceland's surface mass balance. The researchers estimated that by 2100, a third of Iceland's glaciers may be gone and that by 2300, there likely will be no glaciers left in the country.

The researchers' approach could be used to better understand the melting rates of glaciers in other places, such as the Himalayas and Patagonia, Fiamma Straneo, an oceanographer at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California who was not involved in the study, said in the statement.

Scientists are still unsure why the Blue Blob is so much colder than the surrounding waters. Some researchers think it is part of natural variability in sea-surface temperatures in the Arctic that has increased the amount of upwelling of cold water from the deep sea. Others think climate change has disrupted surface currents that push warmer water into the Arctic from tropical regions in the Atlantic.

Regardless of how the Blue Blob came to be, its cooling effect on Iceland will not last forever, and if left unchecked, climate change will cause the total disappearance of Iceland's glaciers in the not-too-distant future.

"In the end, the message is still clear," Noël said in the statement. "The Arctic is warming fast. If we wish to see glaciers in Iceland, then we have to curb the warming."

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus