What was the Black Panther Party?

The legacy of the Black Panthers includes so much more than berets and raised fists.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

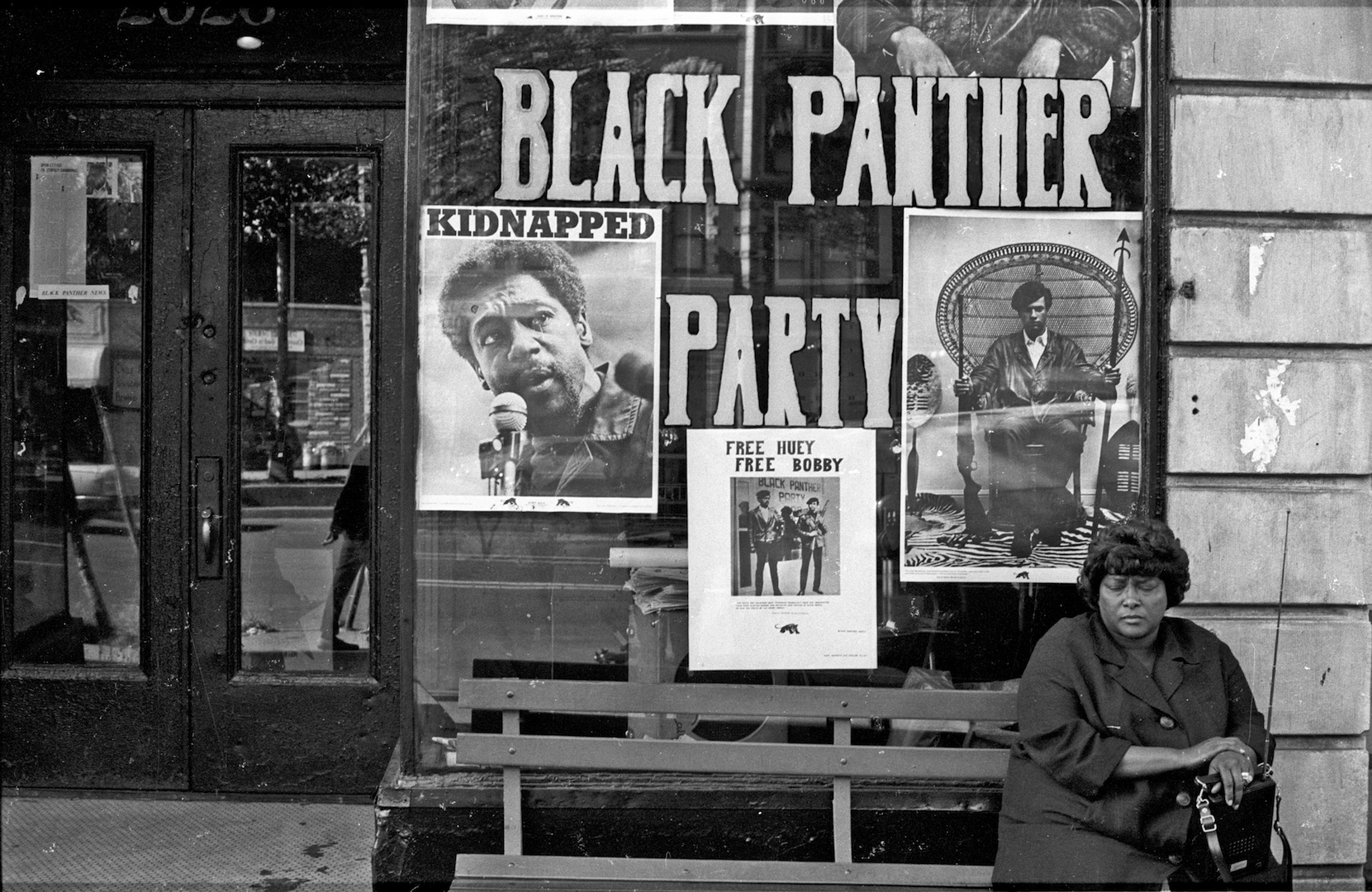

The Black Panther Party was a revolutionary socialist organization formed in Oakland, California. The party was created in the midst of the Black Freedom Movement, which began in the mid 1950s, according to the book "Encyclopedia of Southern Culture" (University of North Carolina Press, 1989).

Amid continued police brutality and oppression in Black neighborhoods, the Black Panther Party sought to defend and provide services to these communities. The party is well-known for its signature uniform of a black beret and raised fist, as well as its ideology of armed self-defense. But its lesser-known accomplishments include hunger-relief programs, improving access to education and providing healthcare to Black communities.

A tumultuous moment in history

In 1966, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, the founders of the Black Panther Party, met as students at Merritt College in Oakland, according to the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. The 1964 Civil Rights Act had passed just two years earlier, outlawing discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin. It was a landmark victory that activists had fought and died for, but it had its limitations, said Adam Ewing, a professor of African American Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Related: How racism persists: Unconscious bias may play a role

The Civil Rights Act meant that segregation in schools, workplaces and public facilities was prohibited (although segregation continues to exist in American society today, including in schools, according to reports in The New York Times and The Washington Post). But racism in numerous other forms still impacted Black communities. "There's poverty; there's systemic and brutal police violence in Black communities; there's a lack of services. And the legislation that was passed did not touch on some of those more entrenched problems," Ewing said.

It was in this historical context that the Black Panther Party emerged. The party aimed for more than just desegregation, Ewing explained. "If the state refuses to honor demands that you feel are necessary for the survival of your community, what do you do?" he said. "The Panthers said, 'Well, we have to then become a revolutionary party. We have to make revolutionary changes to U.S. society.'"

Armed self-defense

The Black Panther Party's overriding ideology and belief in a right to armed self-defense pushed them into the national spotlight.

Newton, a law student at the time of the Black Panther Party's formation, was well versed in California's open carry laws of the time. "Newton and Seale patrolled with law books in one hand and a gun in the other," said former Black Panther David Hilliard during a 2006 panel discussion at the University of Mexico.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Newton and Seale would drive around Oakland, tailing police cars and monitoring police-stops of Black citizens. "They [Newton and Seale] would get out of their car; they had shotguns, constitution and law books. And they would be able to offer advice to the citizens about their rights," Ewing said.

In 1967, the California State Legislature rushed to pass gun control laws in order to put a stop to "Panther Patrol," Ewing said. In response, on May 2, 1967, a small group of Black Panther Party members marched in protest, armed with loaded weapons, into the California State Capitol building, wrote Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Jr. in the book "Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party" (University of California Press, 2013).

The Party's 10-Point Platform

The protest at the California State Capitol building brought the Black Panthers enormous publicity, Bloom and Martin wrote.

"After the Sacramento protest, the party exploded," said Ashley Farmer, a historian at the University of Texas at Austin and author of the book "Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era" (University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

Thousands of college students began flocking to Black Panther rallies, Bloom and Martin wrote. The same month, following coverage of the protests in the Washington Post and New York Magazine, the party published a set of demands, called the 10-Point Platform. According to Bloom and Martin, it included the following statements:

Survival programs

Armed self-defense was an important tenet of the Black Panther Party, but that wasn't all the party stood for, Ewing said. Their "survival programs" brought essential services to otherwise neglected Black communities. The most well-known of these programs was the free breakfast program for school children, Ewing said. Other party services addressed education, transportation and health care.

For instance, the Oakland Community School, an elementary school built by the Panthers, provided education to children throughout the community. Free bus services provided transportation to and from state prisons for family members of inmates. Community-run health clinics provided free care to communities across the country. Free ambulance services transported Black patients to hospitals, as city ambulances often took a long time to come to Black neighborhoods, or would refuse to provide treatment or transport, Farmer said. Sickle cell testing programs raised awareness of the high prevalence of sickle cell anemia in Black populations and helped kick-start research in that field, according to a 2016 article published in the American Journal of Public Health.

"The idea here was that we needed a revolution, but a full scale overturning of racial capitalism obviously was not going to happen tomorrow. So, Huey called [the survival programs] a first aid tool kit — a way to triage problems that were facing the black community," Farmer said.

Rise of the Black Panther Party

The Black Panther Party grew from a small, Oakland-based organization to one with chapters throughout the United States and with international support. In 1970, on a visit to China, Newton was met by crowds holding up signs supporting the Panthers and criticising U.S. imperialism, according to the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Chapters of the organization were established in countries such as the United Kingdom and Algeria, Farmer said.

As membership grew exponentially, new leaders emerged across the United States, and even internationally. Many of the party's most influential figures were women, Farmer said. Estimates suggest that women made up around two-thirds of the party's membership.

Related: 7 reasons America still needs civil rights movements

"Many of the chapters that developed either were founded by women or co-founded by women," Farmer said. "There wasn't a chapter that did not have a Black woman in rank and file, and often in high-ranking positions."

Among the party's influential members was Connie Matthews, a resident of Denmark who served as the party's international coordinator, developing organization efforts outside of the U.S.

There was also Ericka Huggins, who joined the Black Panther Party in its early years alongside her husband, John Huggins. When John died in a 1969 shootout, Ericka helped establish what would become one of the most influential chapters of the Black Panther Party, in New Haven, Connecticut, Farmer said. Later, Huggins would become a key figure in establishing the Oakland Community school, she added.

And Kathleen Cleaver, now a retired law faculty member at Emory University in Atlanta, was the first woman to sit on the Black Panther Party's Central Committee, the group's highest organizing body, Farmer said.

Government pushback

The Black Panther Party's revolutionary ethos led to law enforcement officials flagging the organization as a threat to national security. According to the FBI, then-director J. Edgar Hoover called the Black Panther Party "without question … the greatest threat to internal security of the country."

The FBI launched a counterintelligence program, called COINTELPRO, to closely monitor the Black Panthers. (COINTELPRO was created a decade earlier, when it subjected civil rights activists, such as Martin Luther King, Jr. to similar types of surveillance, according to Stanford University's Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute.) COINTELPRO's goal was to discredit party members and ultimately dismantle the organization.

At one point, Hoover expressed concern over the popularity of the free breakfast program, wrote Bobby Seale and Stephen Shames in their book "Power to the People: The World of the Black Panthers" (Harry N. Abrams, 2016).

"The BCP [Breakfast for Children Program] represents the best and most influential activity going on for the BPP and, as such, is potentially the greatest threat to efforts by authorities … to neutralize the BPP and destroy what it stands for," Hoover said, according to Seale and Shames.

Dismantling the Black Panthers

Throughout the late 1960s and 1970s, COINTELPRO's efforts chipped away at the stability and cohesiveness of the Black Panther Party. Violent altercations involving Black Panther Party members contributed to the public's perception of them as a fundamentally violent organization. Some of these instances occurred as a direct result of COINTELPRO interference, Farmer said.

For example, a 1969 shoot-out at the University of California, Los Angeles that took place between members of the Black Panther Party and a rival organization, was revealed to be an event that happened as a result of letters forged by COINTELPRO agents posing as members of each party in order to stoke division, Farmer said.

FBI raids not only led to the deaths of multiple party members but also an atmosphere of suspicion and division among party members, according to the book "Encyclopedia of the American Left" (Garland Publishing, 1990). With mounting charges pressed against the Black Panther Party by the FBI and local law enforcement, the party began to drown in legal fees, making it difficult for them to continue their work in Black communities. "This was a COINTELPRO strategy to try to mire members in court battles after lengthy jail sentences while they awaited a court date," Farmer told Live Science in an email.

Related: The fury in U.S. cities is rooted in a long history of racist policing, violence and inequality

In 1974, Newton was tried for multiple offenses, included assault and murder, so he fled to Havana, Cuba, to escape prosecution for three years, leaving the party under the leadership of party member Elaine Brown. When Newton returned, he resumed leadership. At that point, the party had already been significantly weakened by in-fighting and external attack, according to "Encyclopedia of the American Left."

The party began to lose its members, Farmer said. Not only were police killing and jailing Panthers, but the group was "also losing popular support because of this misinformation campaign branding them as a terrorist organization."

In 1980, the last issue of the Party's newspaper, The Black Panther, was published. And in 1982, the Oakland Community School closed, wrote Michael X. Delli Carpini in "The Encyclopedia of Third Parties in America" (Sharpe Reference, 2000). After years of declining membership and negative press, the school's closing marked the Party's official end.

Legacy of the Black Panthers

Although the Black Panther Party ceased to exist, many of their survival programs lived on. A few programs continued in their originally established forms. For example, the Carolyn Downs Family Medical Center, a Seattle-based community clinic, was originally founded by the local Black Panther Party.

Other survival programs indirectly influenced the development of community services. For example, the free breakfast program for school-children is likely what inspired the development of today’s mandate that public schools provide free breakfast to students, Ewing said. And the Black Panther Party's Sickle Cell Anemia Research Foundation inspired the federal government's initial funding of sickle cell research, Ewing said.

Related: #BlackBirdersWeek co-founders talk nature and race

The Black Panthers' legacy also lives on in social movements today. For example, the Black Panther Party was an organization largely led and supported by women. Gender politics within the Party were contentious, but the party's emphasis on intersectionality — a term referring to the interconnectedness of different marginalized identities, including race and gender — was pioneering. More recent political and social movements in the U.S. have increasingly included women in leadership roles, thanks in part to the Black Panther Party having normalized gender equality in that way, Farmer said.

Finally, the Black Panthers were unapologetically Black. "This was expressed in their dress, in their approach, in their message. They were not trying to persuade white people of their humanity. They were claiming it," Ewing told Live Science in an email. "In this sense, they were expressing the sentiment at the heart of the slogan, 'Black Lives Matter': The demand that Black humanity be recognized without compromise."

Additional resources:

- Take a look at maps and timelines of the Black Panther Party's main actions, from the University of Washington.

- See images of the Black Panther Party, from the Bob Fitch Photography Archive at Stanford Libraries.

- Watch a short film featuring interviews with former Black Panther Party members, from the Oakland Museum of California.

Isobel Whitcomb is a contributing writer for Live Science who covers the environment, animals and health. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Fatherly, Atlas Obscura, Hakai Magazine and Scholastic's Science World Magazine. Isobel's roots are in science. She studied biology at Scripps College in Claremont, California, while working in two different labs and completing a fellowship at Crater Lake National Park. She completed her master's degree in journalism at NYU's Science, Health, and Environmental Reporting Program. She currently lives in Portland, Oregon.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus