'Perfectly preserved' Neanderthal skull bones suggest their noses didn't evolve to warm air

An analysis of the only intact Neanderthal inner nose bones known to exist reveals that our ancient cousins' enormous noses did not evolve to withstand harsh climates.

A digital analysis of the perfectly preserved nose bones on a bizarre-looking Neanderthal skull reveals that a long-standing theory about Neanderthal noses doesn't pass the sniff test.

The skull comes from the "Altamura Man," one of the most complete and best-preserved Neanderthal skeletons ever found. Speleologists discovered it in 1993 while exploring a cave near the town of Altamura, in southern Italy. Because it is covered in a thick layer of calcite, or "cave popcorn," Altamura Man has not been removed from the cave, to prevent damage to the bones. This Neanderthal likely died in the exact place the skeleton was found, between 130,000 and 172,000 years ago.

The "perfectly preserved" nasal cavity of Altamura Man is unique in the entire human fossil record, according to a study published Monday (Nov. 17) in the journal PNAS. These rare and fragile bones can therefore contribute important information to the question of whether Neanderthals' faces were adapted to cold climates.

"The general shape of the nasal cavity and nasal aperture in Neanderthals follows a quite constant trend," study lead author Costantino Buzi, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Perugia, told Live Science in an email. "In general, it starts large but gets larger during their evolution, with very large nasal openings in the last populations of the species."

One theory for Neanderthals' large noses is that they had equally large sinuses and an enhanced airway that evolved as adaptations to living in cold, dry environments. Their particular nasal anatomy may have been useful for warming and humidifying the air before it reached their lungs. But all previous studies of Neanderthal nasal anatomy were based on approximations of the delicate bones in the nose cavity, since these bones — the ethmoid, vomer and inferior nasal conchae — were broken or missing in every Neanderthal skull ever found.

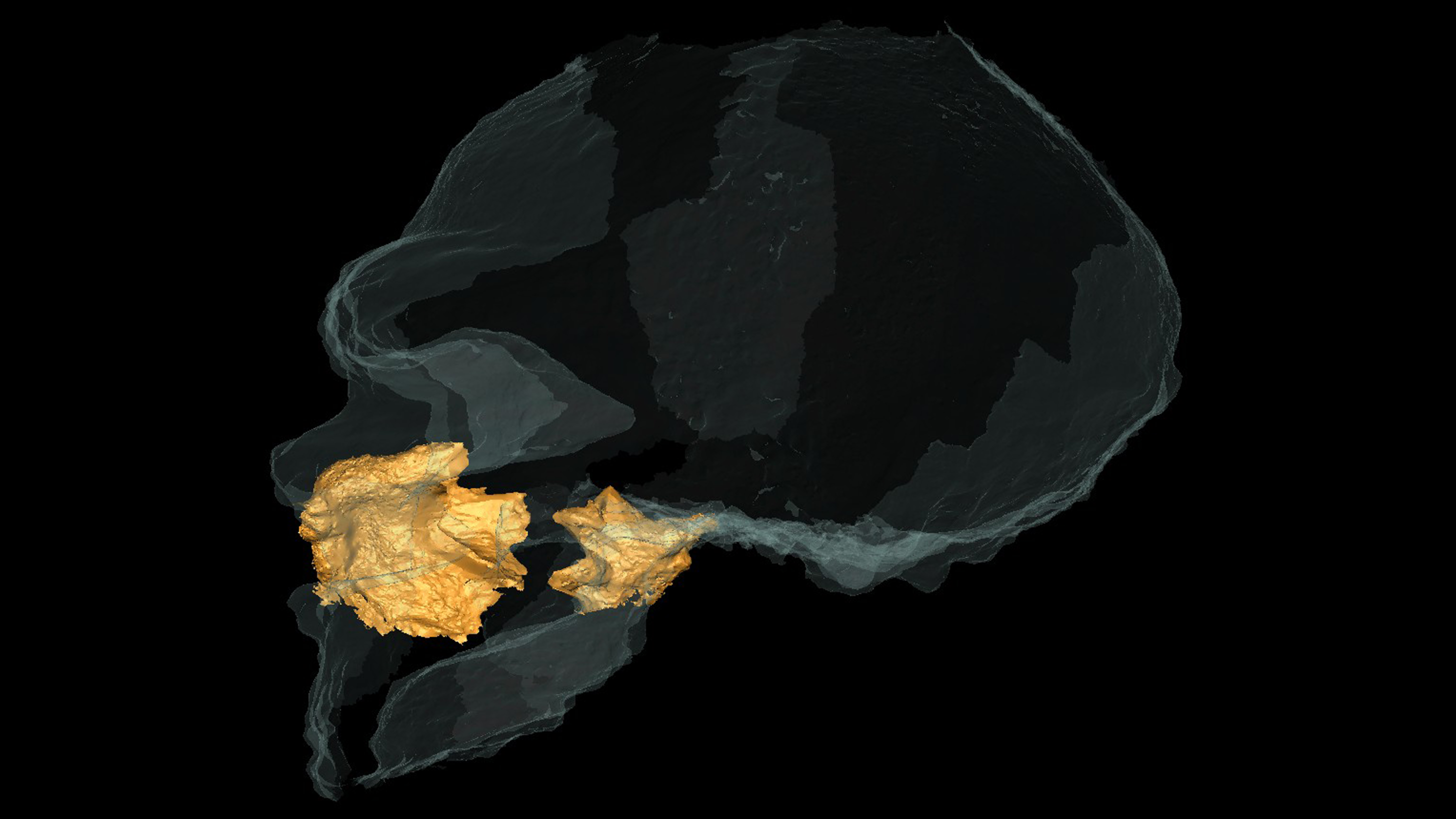

Buzi and colleagues have been working on a "virtual paleoanthropology" project to document and digitize Altamura Man without removing the specimen from the cave. Using endoscopic probes, the researchers acquired video from inside the nasal cavity of the skull and created 3D photogrammetric models of Neanderthal nose bones for the first time.

When the researchers analyzed the endoscopic images, they found that Altamura Man's inner nasal structures were neither unique nor substantially different from those of modern humans. Although the rest of the Neanderthal's skeleton appeared to be adapted to the cold — with shorter limbs and a stockier build than those of modern humans — his nose was not.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new study is informative, Todd Rae, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Sussex who was not involved in the work, told Live Science in an email, "in that two of the three previously proposed unique features of the Neanderthal nasal cavity do not appear to be present in this specimen." The lack of unique traits, Rae said, "shows that there is variation in the species that was not previously known."

Buzi agreed that Neanderthals probably had a certain degree of intraspecies variability, but he cautioned that solid evidence for this variation is limited, since only Altamura has provided evidence of the internal structures of the Neanderthal nose.

But the answer to why Neanderthal noses were big might not have anything to do with biological adaptations to cold weather, Rae said.

"All earlier species of Homo have wide noses," Rae said, and "most Homo sapiens have a wide nose — only northern European/Arctic people don't, a vanishingly small proportion of the species."

Rather than viewing the Neanderthal nose as a unique adaptation to cold weather, it is better to understand it as an efficient way to change the temperature and humidity of the inhaled air required to run Neanderthals' massive bodies. Numerous environmental pressures and physical constraints likely helped shape the Neanderthal face, Buzi said, "resulting in a model alternative to ours, yet perfectly functional for the harsh climate of the European Late Pleistocene."

Neanderthal quiz: How much do you know about our closest relatives?

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.