Neanderthals passed down their tall noses to modern humans, genetic analysis finds

A new genetic analysis found that the size of Neanderthal noses was passed down to modern humans.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Neanderthals were equipped with tall noses that could warm and moisten the cold and dry air around them in chilly climates — an adaptation that may be the result of natural selection.

These sizable schnozzes were likely helpful to Neanderthals; once anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) left Africa and joined Neanderthals up north in Eurasia, the two mated, with Neanderthals gifting Homo sapiens their bigger-nose genes, a new study finds.

Scientists made the discovery after analyzing DNA taken from more than 6,000 volunteers recruited from Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Mexico and Peru who had Latin American, mixed European, Native American or African heritage, and compared their genetic information to photographs of their faces, according to a study published May 8 in the journal Communications Biology.

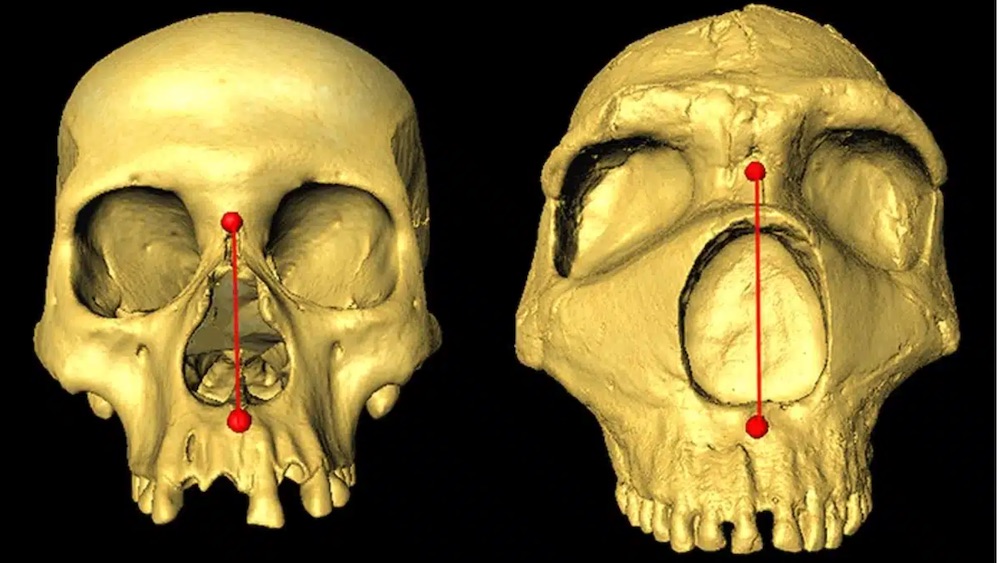

After measuring the distances between different points on each face, such as the height of a person's nose, the researchers compared those data to see if those characteristics were associated with certain genetic markers, according to a statement.

The researchers successfully identified 33 new genome regions that corresponded with facial features. One in particular, ATF3, not only had Neanderthal origins but also defined nose height. They found that study participants with Native American ancestry "had genetic material in this gene that was inherited from the Neanderthals, contributing to increased nasal height," according to the statement.

Related: Human and Neanderthal brains have a surprising 'youthful' quality in common, new research finds

"It has long been speculated that the shape of our noses is determined by natural selection; as our noses can help us to regulate the temperature and humidity of the air we breathe in, different shaped noses may be better suited to different climates that our ancestors lived in," lead author Qing Li, a faculty member in the Department of Environmental Science and Engineering at Fudan University in Shanghai, said in the statement. "The gene we have identified here may have been inherited from Neanderthals to help humans adapt to colder climates as our ancestors moved out of Africa."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 2021, the same team of researchers conducted a related study that identified a gene that influenced lip shape. That gene, called TBX15, was inherited from the Denisovans, modern-human relatives who lived in Asia and went extinct approximately 30,000 years ago. The Denisovans interbred with Homo sapiens, passing along this genetic attribute. By examining data from this previous study, the researchers discovered that, like Native Americans, East Asians were also more likely to have the ATF3 nose gene.

So what was the benefit of having a taller nose thousands of years ago?

"When you live in colder climates, your nose gets narrower so that it can warm cold air before it reaches the lungs," study co-author Kaustubh Adhikari, a statistical geneticist at University College London, told Live Science. "We think that when [Homo sapiens] came into colder regions where Neanderthals were already living, they bred with them and they passed along these [genetic] benefits to their children, which helped give them a leg up with adaptation."

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus