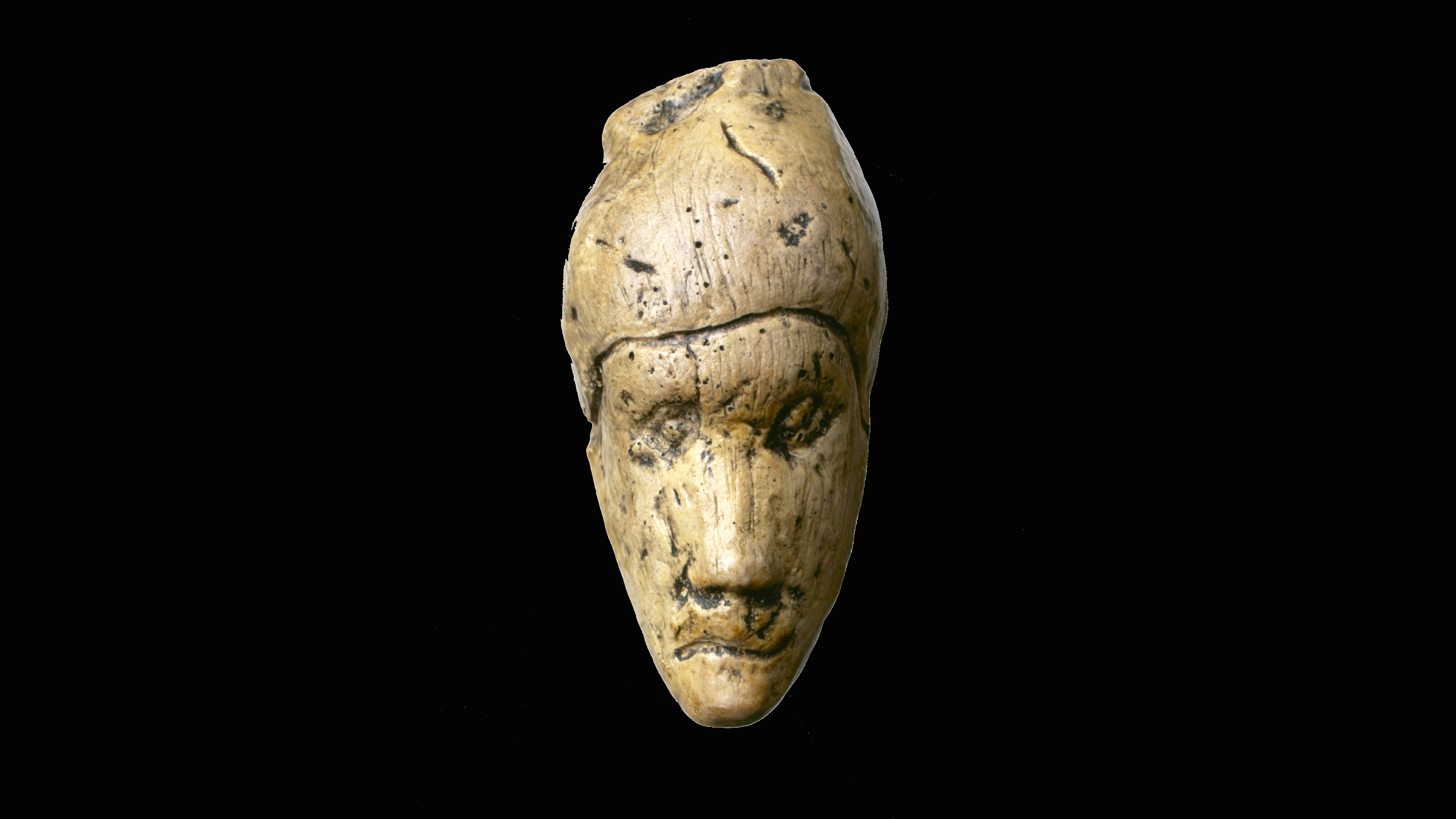

Dolní Věstonice Portrait Head: The oldest known human portrait in the world

A tiny head carved from mammoth ivory looks back at us from the Stone Age.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Name: Dolní Věstonice Portrait Head

What it is: A face carved out of mammoth ivory

Where it is from: The South Moravian region of the Czech Republic

When it was made: About 24000 B.C.

What it tells us about the past:

This sculpture, discovered at the archaeological site of Dolní Věstonice in the Czech Republic in the 1920s, is considered the oldest surviving portrait of a person anywhere in the world, at 26,000 years old.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Carved with stone tools out of mammoth ivory, the tiny head measures just 1.9 inches (4.8 centimeters) tall and 1 inch (2.4 cm) wide. The sculpture appears to represent a woman's face, with engraved eyes, a dimpled chin, and a raised nose and mouth. She may be wearing her hair in an updo or under a hat. Unlike other objects from the site — such as the Venus of Věstonice, which lacks facial features — this face seems to be individualized, making it the earliest known depiction of a specific person.

During the Upper Paleolithic period, a band of mammoth hunters set up camp at Dolní Věstonice, which is now a small village near the southern border of the Czech Republic. This cluster of settlements, sometimes called the "Stone Age Pompeii," has yielded tens of thousands of ceramics, stone tools and bone objects over the past century of excavations, along with numerous burials.

In one of these burials, covered in red ocher and arrayed with 10 drilled fox teeth, excavators discovered the skeleton of a middle-aged woman in 1949. Her skull was asymmetrical, potentially due to a traumatic childhood injury. When researchers used forensic techniques to reconstruct the woman's face from the skull in 2018, they discovered it was very similar to the tiny ivory carving, whose left eye is significantly smaller than the right.

Dolní Věstonice is unique in Europe for its abundant artifacts dating to the Late Gravettian period (29000 to 24000 B.C.), including some of the earliest kiln-fired pottery in the world, so it is unsurprising that this little head carved from mammoth ivory is likely the earliest personal portrait in the world.

Many artifacts from Dolní Věstonice, including this sculpted head, can be found on display at the Anthropos Pavilion, a museum in Brno, Czech Republic.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus