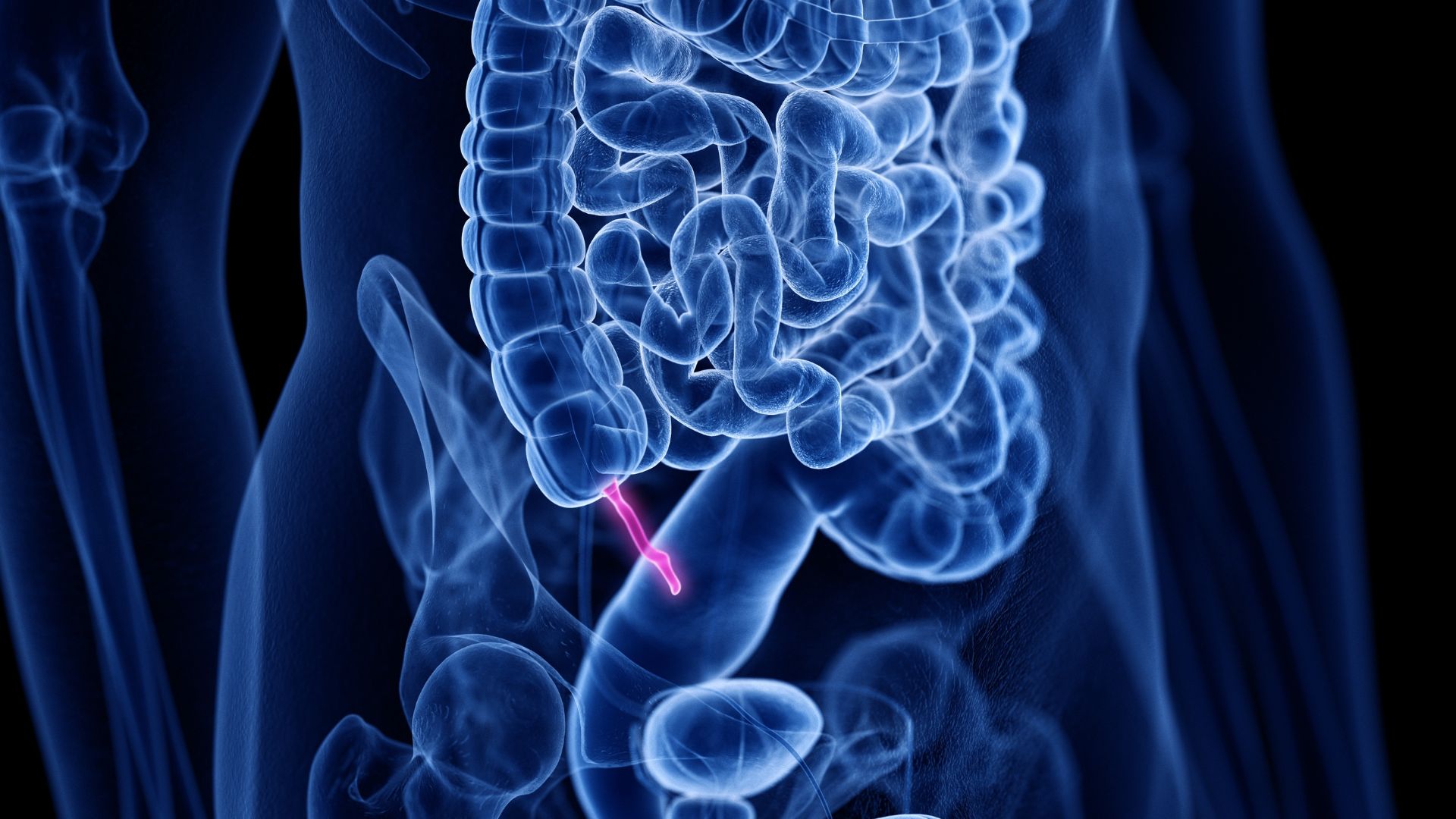

Appendicitis: Causes, symptoms and treatment

Appendicitis refers to the inflammation of a small structure in the gastrointestinal tract. The condition can lead to dangerous complications.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Appendicitis is inflammation of the vermiform appendix (or just the appendix, for short), a little structure within the lower gastrointestinal tract.

In appendicitis, the appendix swells, causing a condition that is classified as either acute or chronic. Both acute and chronic appendicitis are characterized by some of the same symptoms, especially abdominal pain. However, while chronic appendicitis features pain that waxes and wanes over periods of weeks, months or years, and that tends to be milder, acute appendicitis has symptoms that are more severe and emerge rapidly, typically over 12 to 24 hours.

Acute appendicitis requires immediate treatment to avoid life-threatening complications.

What causes appendicitis?

Appendicitis develops when the lumen (the hollow, inner region of the vermiform appendix) becomes blocked or parts of the gastrointestinal tract to which the appendix is attached become blocked. Such blockages can result from material, such as a piece of fecal matter blocking the hollow interior of the appendix, or they may stem from the presence of a tumor.

This leads to an inflammatory reaction to infectious agents that become trapped inside the appendix, since the blockage prevents these agents from being cleared away by normal secretions and movements of bodily fluids. Usually, such an infection is caused by bacteria, but it also can be driven by a virus or parasite.

The appendix then swells, causing pain, which is exacerbated when the swelling pushes on nearby blood vessels in a way that cuts off the blood supply to the appendix. Obstructed blood supply leads to ischemia, meaning a lack of blood flow to the tissue. This weakens the tissue, and in cases of acute appendicitis, this weakening can be drastic enough to put the appendix at risk of perforating (developing small holes) or even rupturing.

Chronic appendicitis also features episodes of inflammation that can decrease blood supply to the appendix. However, any episode that reaches a level of severity bad enough to cause perforation is then called acute appendicitis and treated as such.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Risk factors for appendicitis

Appendicitis is fairly common: 8.6% of the male population and 6.7% of the female population will have the condition at some point in their lives.

While a family history of appendicitis may be a risk factor for male patients, who have a slightly higher overall risk of the condition than female patients do, the only reliable predictor of risk for everyone is age. Appendicitis is most common between the ages of 10 and 20, and then there is another, smaller peak in older people that arises in the early 40s, peaks around age 65 and then gradually decreases again. This is called a bimodal age distribution.

Although appendicitis most commonly occurs in the aforementioned age ranges, it's important to keep in mind that the condition can occur at any age.

Also, since chronic appendicitis is characterized by waxing and waning episodes, and since any such episode can potentially become acute, people who suffer from chronic appendicitis are also at risk for acute appendicitis.

What are the symptoms of appendicitis?

According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, the symptoms of appendicitis include the following:

- abdominal pain

- nausea

- lack of appetite

- vomiting

- painful urination

- fever

Pain is the dominant symptom of both chronic and acute appendicitis. As noted above, the pain waxes and wanes over weeks, months or years in cases of chronic appendicitis, whereas symptoms of acute appendicitis develop abruptly.

Typically, the pain of acute appendicitis begins gradually as a dull sensation around the navel that develops over 12 to 24 hours. Then, the pain shifts to the right side of the lower abdomen, classically to a location that surgeons call the "McBurney's point." It's important to keep in mind, however, that many people experience variations of this classic pattern of pain progression, or patterns that are very different. Pregnancy notoriously makes the development of appendicitis confusing, because the growing womb shifts organs to different locations, making the McBurney's point less likely to be the focus of the pain.

It should be noted that a very small number of people carry their appendix on the left side of the body, instead of the right side, so it's technically possible for pain in the lower left abdomen to be the result of appendicitis.

How is appendicitis diagnosed?

In evaluating patients for possible appendicitis, physicians and surgeons order blood tests to determine if the number of white blood cells, a type of immune cell, is elevated. Doctors also perform a physical examination in which the abdomen and legs are manipulated in certain ways to elicit classic signs of appendicitis, such as McBurney's sign. But generally, they do not diagnose appendicitis based on the physical examination alone.

To add to the information obtained from physical examination and blood tests, doctors order or perform imaging of the abdomen. Usually, the first imaging is ultrasound scanning to reveal if the appendix is swollen. If the ultrasound imaging does not give a clear result, doctors will order either computed tomography (CT) scanning or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen to get a better look. Currently, CT is the most accurate method for confirming appendicitis.

Complications of appendicitis

In cases of acute appendicitis, the imaging and laboratory workup will be used not only to confirm that appendicitis is present but also to detect or rule out the following complications. The presence or absence of these complications determines whether nonsurgical treatment can be considered.

- Perforation or rupture: One or more holes opens in the appendix, making it possible for the infection to spread through the abdomen and pelvis. This can lead to an abscess (the infection leaks out of the appendix but becomes enclosed in a ball of pus), peritonitis (the abdominopelvic cavity becomes infected) or sepsis (the infection spreads throughout the bloodstream).

- An abscess on or near the appendix or elsewhere in the abdomen: As noted above, this is basically a swollen accumulation of pus.

- Evidence of a possible tumor near the appendix, or within it.

- An appendicolith: This term refers to a calcified deposit within the appendix. CT scanning is particularly good at revealing this.

Generally, the aforementioned complications are issues related to acute appendicitis, although it is sometimes possible for a small abscess to form in connection with chronic appendicitis.

How is appendicitis treated?

If you have appendicitis with any of the above complications, surgery is mandatory, but there is no need to worry. Appendectomy is a safe, routine operation. In nearly all cases, such complications emerge in the setting of acute appendicitis, rather than chronic. If they do emerge in someone whose appendicitis has been chronic, the case is then considered to be acute, as explained previously.

Usually, the procedure is performed laparoscopically, meaning that surgeons make just a few very tiny incisions in the patient's abdomen and the appendix is pulled from the body through a tube. Recovery from laparoscopic appendectomy (sometimes called "lap-appy") is fairly rapid. In fact, because recovery is easy, a patient may decide, in consultation with their doctor, to have their appendix removed even if they have an uncomplicated case, for reasons that will be discussed below.

The idea that an inflamed appendix must always be removed dates back to the late 19th century, when antibiotics weren't available and surgeons began performing appendectomies (removal of the appendix) routinely as a way to prevent death that would result if a swollen appendix perforated. Perforation is a feared complication because it can lead to abscess, peritonitis or sepsis, which can be fatal.

Nowadays, however, many people with appendicitis don't need surgery and can recover with just antibiotics.

Nonsurgical treatment is appropriate for a certain fraction of appendicitis cases. Evidence shows that people with acute appendicitis who have not developed complications can receive only antibiotics, with a success rate of about 70%. This means that in about 70% of people who receive the right kind of antibiotics on the correct schedule to treat uncomplicated appendicitis, the appendicitis will clear and then not recur. Of course, this also means that about 30% of uncomplicated appendicitis cases treated nonsurgically will recur, so many people opt for surgical treatment even when they do not experience complications.

When it comes to chronic appendicitis, patients may experience episodes for years without developing complications. But even so, it's not uncommon for doctors to offer antibiotics for flare-ups and to offer surgery to treat the condition, since removing the appendix ends the problem for good.

Scientists are evaluating the influence of age and other factors on the success rate of nonsurgical treatments for appendicitis. Treating the condition with antibiotics, alone, used to require that patients stay in the hospital and receive the drugs intravenously for 14 to 21 days. Today, however, doctors can successfully treat appendicitis by giving patients intravenous antibiotics for as few as four days and then antibiotic pills for seven to 10 days. These pills can be taken at home, so patients can be discharged from the hospital at that time.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

David Warmflash is a medical researcher, astrobiologist, science communicator, and author, located in Portland, Oregon. He holds an MD from Tel Aviv University Sackler School of Medicine and has conducted research in astrobiology, space biology, and space medicine during research fellowships at NASA's Johnson Space Center, the University of Pennsylvania, and Brandeis University, and in collaboration with The Planetary Society and the Israeli Aerospace Medicine Institute.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus