Mummified baboons may identify lost land of Punt, ancient Egypt's trading partner

Baboons illuminate an ancient network of trade.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Mummified baboons may reveal the location of the lost land of Punt, ancient Egypt's mysterious and most-valued trading partner.

Ancient Egyptian texts make clear that Punt was somewhere to the south and east of Egypt, a place that could be reached by either land or sea. Unfortunately, a large region meets that description, ranging from the Arabian Peninsula to northeast Somalia, southern Sudan and northern Ethiopia or Eritrea. To this day, no one knows the location of Punt.

Nathaniel Dominy, a primatologist and professor of anthropology at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, realized that there might be a way to narrow down Punt's location: baboons. These primates aren't native to Egypt, but ancient Egyptians imported and mummified them by the barrel load for centuries. In some temples and necropolises, there are hundreds of baboon mummies. Many seem to have lived long lives in captivity as pets or service animals (they're depicted in some tomb paintings as "police dogs," helping the authorities chase down thieves). Others may have been kept as part of the worship of the god Thoth, who was sometimes depicted as having a baboon head.

Related: Photos of ancient Egyptian cat mummies

"The Egyptians described importing baboons from Punt," Dominy told Live Science in an email. That meant that if the native land of the baboons could be determined, it would lead Dominy and his colleagues right to Punt.

A molecular map

To trace the baboons' origins, Dominy and his colleagues looked at levels of particular variations of strontium and oxygen in the animals' tissues. The molecular variations, called isotopes, are present in soil and water, and they vary from place to place. They became incorporated into the baboons' bodies from the food they ate and the water they drank. Different tissues hold a record of where the animals ate and drank at different times in their lives. For example, tooth enamel forms in the first one to three years of a baboon's life, so oxygen and strontium isotopes in enamel can reveal where a baboon was born. Hair, on the other hand, holds a record of the last few months of an animal's life.

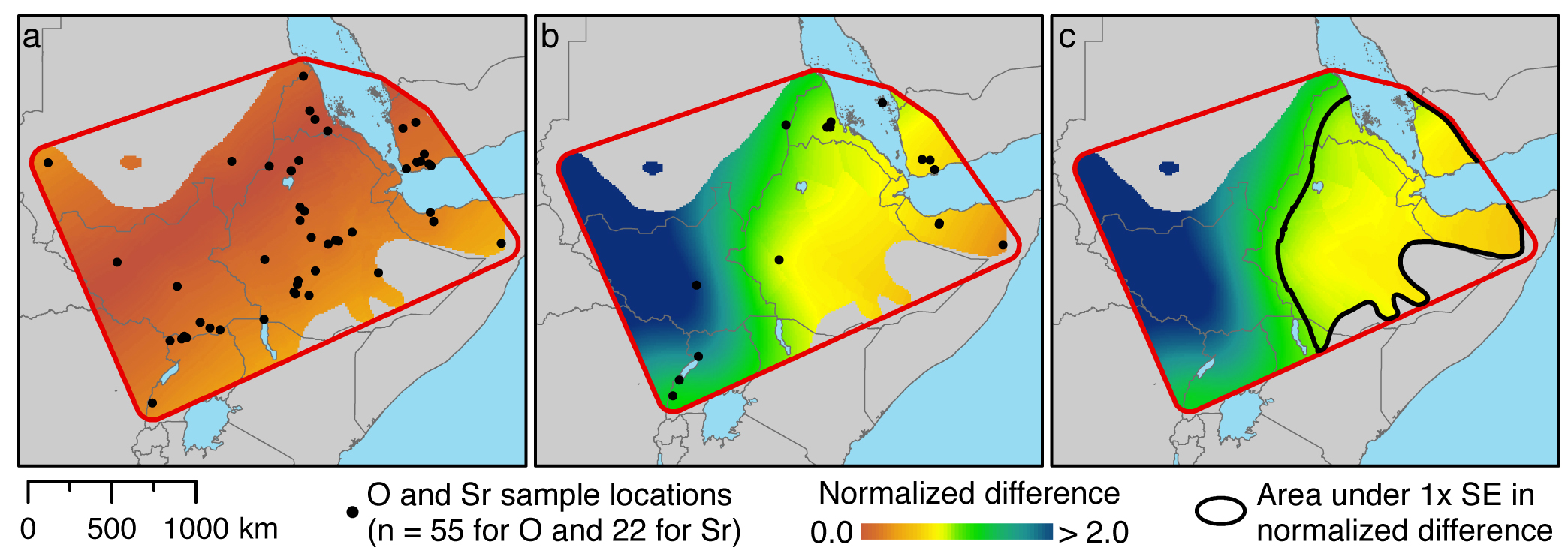

The researchers first analyzed strontium and oxygen levels from 155 modern baboons in 77 different locations to create a molecular map of what these levels look like in different regions. They then analyzed two baboon mummies from the New Kingdom period (1520 B.C. to 1075 B.C.) and five from the Ptolemaic period (after 332 B.C.).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They found that the New Kingdom baboons were born outside of Egypt, in the region that is modern-day Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia, none of which share a border with Egypt. This suggests that Egpytian sailors were quite capable seafarers, able to traverse the length of the Red Sea, Dominy said.

"Punt existed in the southern Red Sea region, very likely on the coasts of Eritrea and Somaliland," he wrote in his email to Live Science.

The mummies from the later Ptolemic period, on the other hand, did not seem to be imported. They likely were captive-bred in Egypt, which fits with historical texts describing baboon-breeding in the Egpytian city of Memphis, Dominy said.

The findings should be considered provisional, Dominy and his colleagues reported on Dec. 15 in the journal eLife, with more studies needed on more baboon mummies to paint a fuller picture of the ancient primate trade. However, the results suggest that the sacred baboons were one of the driving forces behind the development of long-distance trade in ancient Egypt, the researchers conclude.

Associate editor Laura Geggel contributed reporting to this article.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus