Dead baby shark that washed up on UK beach was likely aborted by its mother

Analysis of the elusive shark's remains show that it had not fully developed.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A baby shark that recently washed up on a beach in the United Kingdom, was likely aborted by its mother shortly before birth, experts have concluded.

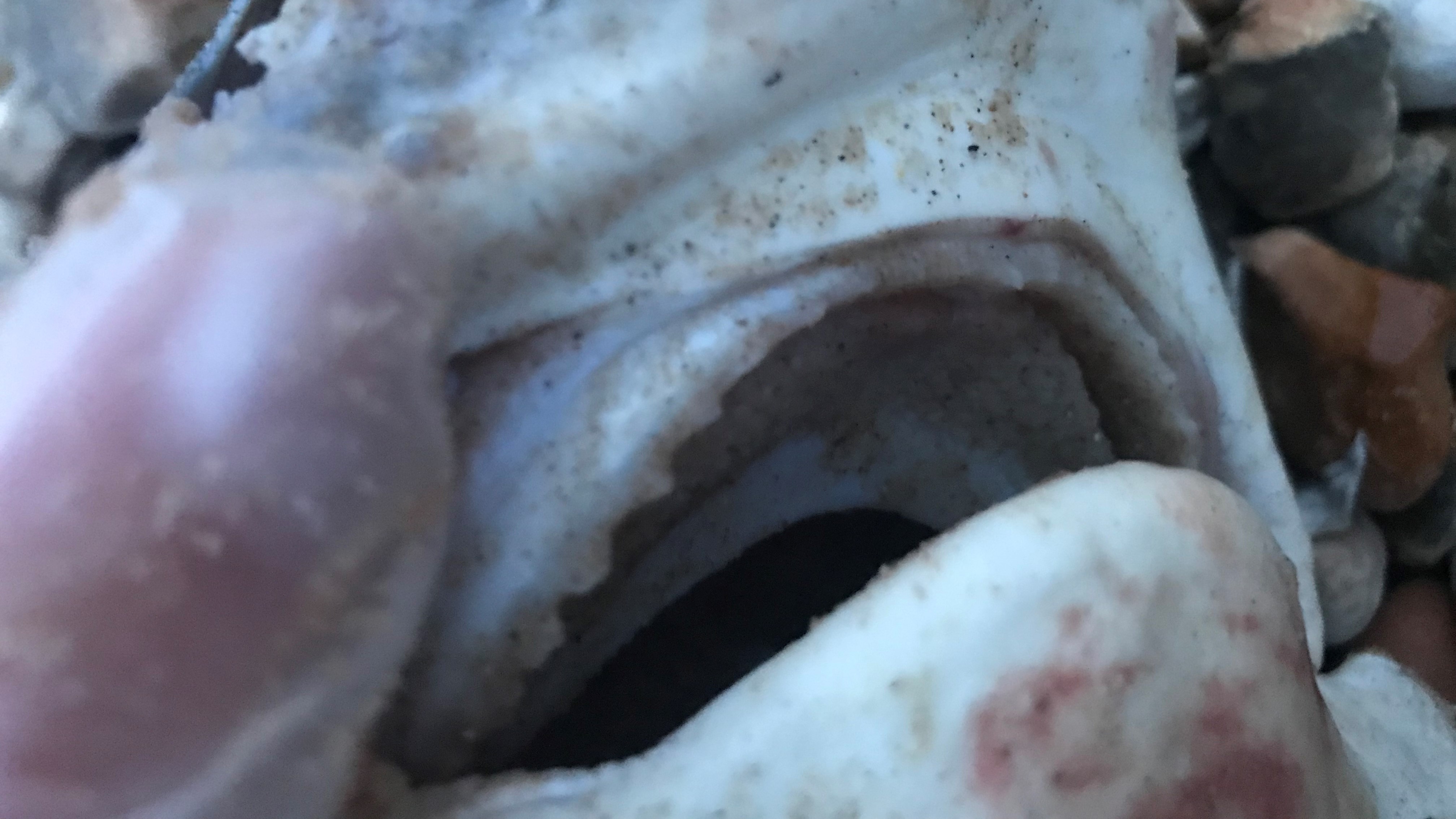

The dead shark was found May 13 on Southbourne beach in Bournemouth, southern England, by Georgina and Tim de Glanville, according to local news site Bournemouth Echo. It was identified as a common thresher shark (Alopias vulpinus), which is rarely seen despite being fairly common in U.K. waters. A team from the local council retrieved the shark's corpse and sent it to experts for analysis.

"It was a pretty big surprise to hear that a thresher had washed up," Georgia Jones, a conservation ecologist at Bournemouth University who carried out a necropsy on the shark's remains, told Live Science. "We've had some caught and released locally, but this is the first to have washed up."

Common threshers can grow to be 20 feet (6 meters) long. Much of that length is their long, crescent-shaped tails, which they whip through the water to stun their prey, Jones said. Threshers are "notoriously elusive" and are rarely glimpsed near the U.K. coast because they live in deeper waters, she added.

Related: Rare, alien-like baby 'ghost shark' discovered off New Zealand coast

The fetal shark, which was identified as a female due to its lack of claspers (a shark's equivalent of a penis), was around 3 feet (0.9 m) long, which is slightly smaller than the average body length of a newborn thresher shark, according to a Twitter thread by Jones.

The shark's diminutive size, as well as other anomalies, such as a lack of front teeth and the absence of growth rings in the shark's vertebrae, suggest that the pup may have been aborted by its mother, Jones said. "Abortion is more common in sharks, rays and skates than previously recognized," and has been recorded in species that are closely related to thresher sharks, she added.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sharks, rays and skates belong to the class of fish known as the Chondrichthyes, which have skeletons made of cartilage instead of bone. In 2018, a study published in the journal Biological Conservation revealed that abortions among Chondrichthyes, which may be triggered by high-stress situations such as being chased by a predator or being caught by humans, are much more frequent than once thought. However, abortion rates can vary greatly between different species.

In the case of the dead thresher shark, it's possible that the abortion may have been triggered in the mother after she was accidentally caught by fishers, which is known as bycatch, Jones said. Bycatch is a major reason why threshers are listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List as vulnerable to extinction, she added.

The necropsy of the preterm shark also gave Jones a chance to examine the unusual physiology of thresher sharks. While most sharks are ectothermic, or cold-blooded, thresher sharks are endothermic, or warm-blooded, which means they have different types of muscles and a complex blood vessel system that isn't seen in most other sharks. Being endothermic gives thresher sharks "a warm brain and eyes so they can operate exceptionally well in cooler water," and enhances their swimming performance, Jones explained.

The southern coast of the U.K. is a thresher hot spot because the area is part of an important migration route for the species, and the shark mother may have been traveling along that route when she aborted her pup, Jones suggested However, it is unclear exactly where the dead shark came from. The pup's stomach and liver, as well as part of its iconic tail, had already been removed by scavengers when it washed up, hinting that it had been in the water for several days and could have floated to the Bournemouth shore from a great distance away, Jones said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus