Evolutionary Twist: Snails Trade Awkward Sex for Survival

Snails whose shells coil counterclockwise have trouble hooking up with snails whose shells twist clockwise since their bodies don't line up properly. Turns out, the contrary snails trade awkward sex for an increased chance of not being eaten by snakes, researchers find.

Scientists investigated land snails in Japan and Taiwan whose shells turned counterclockwise. Since the coil direction made sex difficult, scientists were puzzled as to how a mutation causing this reversal could have been passed down to offspring when snail shells overwhelmingly curl clockwise. Nevertheless, such reversals have happened many times in snail evolution, leading to a number of counterclockwise snail species.

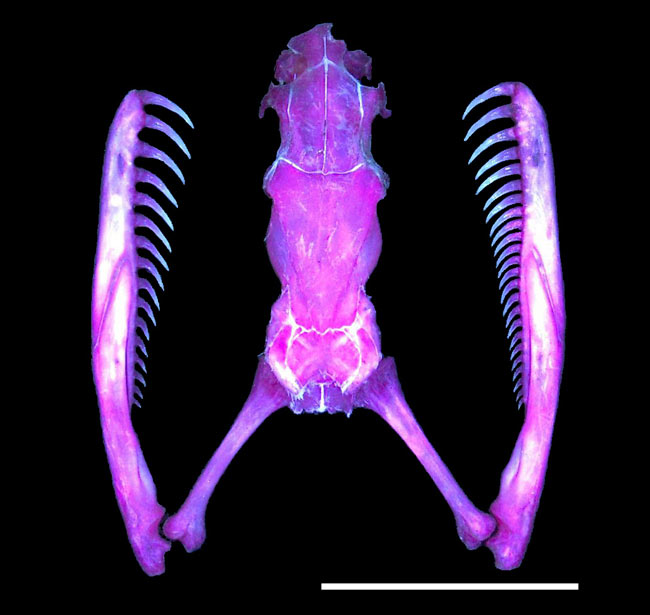

The key, researchers discovered, might be predators such as the snake known as Iwasaki's snail-eater (Pareas iwasakii). The serpent attacks snails from behind, grasping the victim's shell with its upper jaw and the soft body with its lower jaw. It then wiggles the right and left part of its lower jaw back and forth to extract the meat. [Video - See snake try to snag counterclockwise snail]

Given that most snails twist clockwise, the snakes evolved specialized lower jaws that matched this coiling with more teeth on the right side than on the left, and they always angle their heads leftward during attacks. As such, they can rarely grab onto shells that spiral the other way.

Earlier, the researchers found that counter-clockwise snails were more difficult to eat, but now they discovered precisely how much harder they were for snakes.

In experiments with a clockwise species of snail, Satsuma mercatoria from Okinawa, Japan, and a closely related counterclockwise species, Satsuma perversa from Kume, Japan, none of the clockwise snails survived an introduction to Iwasaki's snail-eater. In the same situation, 87.5 percent of the counterclockwise snails survived, suggesting it was spiraling that made the difference.

This showed this spiraling clearly helped them survive.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In addition, in the new research the scientists investigated the geographical distribution of Iwasaki's snail-eater and related snail-eating species of snakes worldwide. They found that counterclockwise-spiraling snails made up only 5 percent of all genera, or groups of species, outside the ranges of these serpents, but were nearly 12 percent of all genera inside their ranges. The snakes apparently supplied the lethal pressure that caused the reversed snails to flourish.

"Our study shows the important role of interactions with snake predators in snail speciation," researcher Masaki Hoso, an evolutionary biologist at Tohoku University in Miyagi, Japan, told LiveScience.

Speciation, the formation of new species, "is the first step in the generation of biodiversity," Hoso added. "Further investigation of the ecological consequences of speciation should help complete our understanding of biodiversity."

The scientists detailed their findings online Dec. 7 in the journal Nature Communications.

- Why So Many Animals Evolved to Masturbate

- Top 10 Swingers of the Animal Kingdom

- Q&A: Discoverer of Dead Gay Duck Sex

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus