In the Tool Shed, Apes Plan Ahead

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

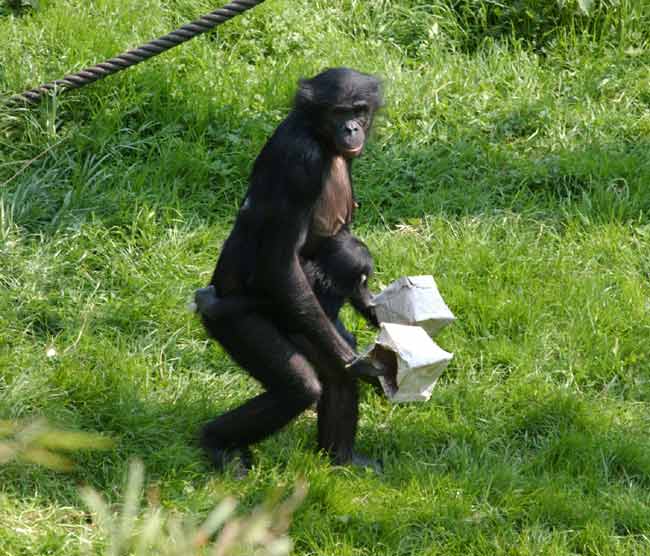

You can give an ape a tool, but you can’t make him use it, especially if he’s just hanging on to it for later use.

A new study reveals that like a person drawing up a grocery list or packing sunscreen and snorkel for a beach vacation, apes plan ahead and collect tools they might need for future tasks.

The findings suggest that the precursor skills for planning ahead evolved in the common ancestor for humans and all other great apes at least 14 million years ago.

The study is detailed in the May 19 issue of the journal Science.

Delayed gratification

Planning for future needs, and not simply addressing the present, is one of the most important cognitive abilities humans posses. It is a demanding task due to the long delay between performing an action and getting rewarded for it.

Many animals can work out and execute several steps in order get what they want. For example, chimpanzees crack nuts with stones and New Caledonian crows fashion hook-shaped tools to collect insects. But these actions solve immediate hunger demands, not future ones.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The only evidence of future planning in animals other than humans is the food storage strategies of scrub jays, according to the researchers involved in the new study. These clever birds transport cached food from old storage sites to new ones if they suspect another bird has been spying on them.

The tool shed

To determine if apes can also perform this type of "mental time travel," Nicholas Mulcahy and Josep Call, researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, enlisted five bonobo chimpanzees and five orangutans for an experiment.

The researchers first led the animals into a room and taught them how to use a tool to get a food reward. Then the apes were directed to a "tool shed" containing tools for reaching grapes and juice bottles. Two of the tools were well suited for the task, while six were not.

After an ape made its selection, it was not allowed access to the goodie dispenser for an hour, so the animal hauled the tool back to a waiting room for storage.

When the researchers allowed the animals to have a go at the dispenser, the apes returned with a suitable tool and retrieved their treat in less than 5 minutes about 30 percent of the time.

One orangutan, a female named Dokana, was particularly adept at planning ahead. She returned to the feeding area with the correct tool for the task nearly every time. Even when she brought back the wrong tool, she figured out how to alter it to make it work anyway.

In a second test, the researchers extended the wait time to 14 hours and ran the test with Dokana and a male bonobo named Kuno. Dokana took tools with her in all 11 trials, and returned with the proper tool seven times. Kuno did even better, returning with the right tool eight times.

Reading an ape's mind

The authors suggest that selecting a tool, which has no value in itself, is evidence that the apes are actually planning ahead, since the animal knows that the tool will come in handy later on.

However, figuring out an ape's intentions isn't a cinch, as Thomas Suddendorf of the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, notes in a commentary in the same issue of the journal.

"Much clever experimentation is required to determine what foresight apes have and what the limits of this ability are," he writes.

- Top 10 Missing Links in Human Evolution

- Human and Chimp Ancestors Might Have Interbred

- In Human Nature Study, Apes Can Cook or Use Vending Machines

- Monkeys Use 'Code Words' to Warn of Predators

- Like Humans, Chimps Bow to Social Pressure

- Gorillas Photographed Using Tools

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus