7.5-foot-long sword from 4th-century Japan may have 'protected' deceased from evil spirits

Archaeologists have unearthed an oversized ceremonial iron sword and a bronze mirror shaped like a shield from a 1,600-year-old burial mound in Nara, Japan.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

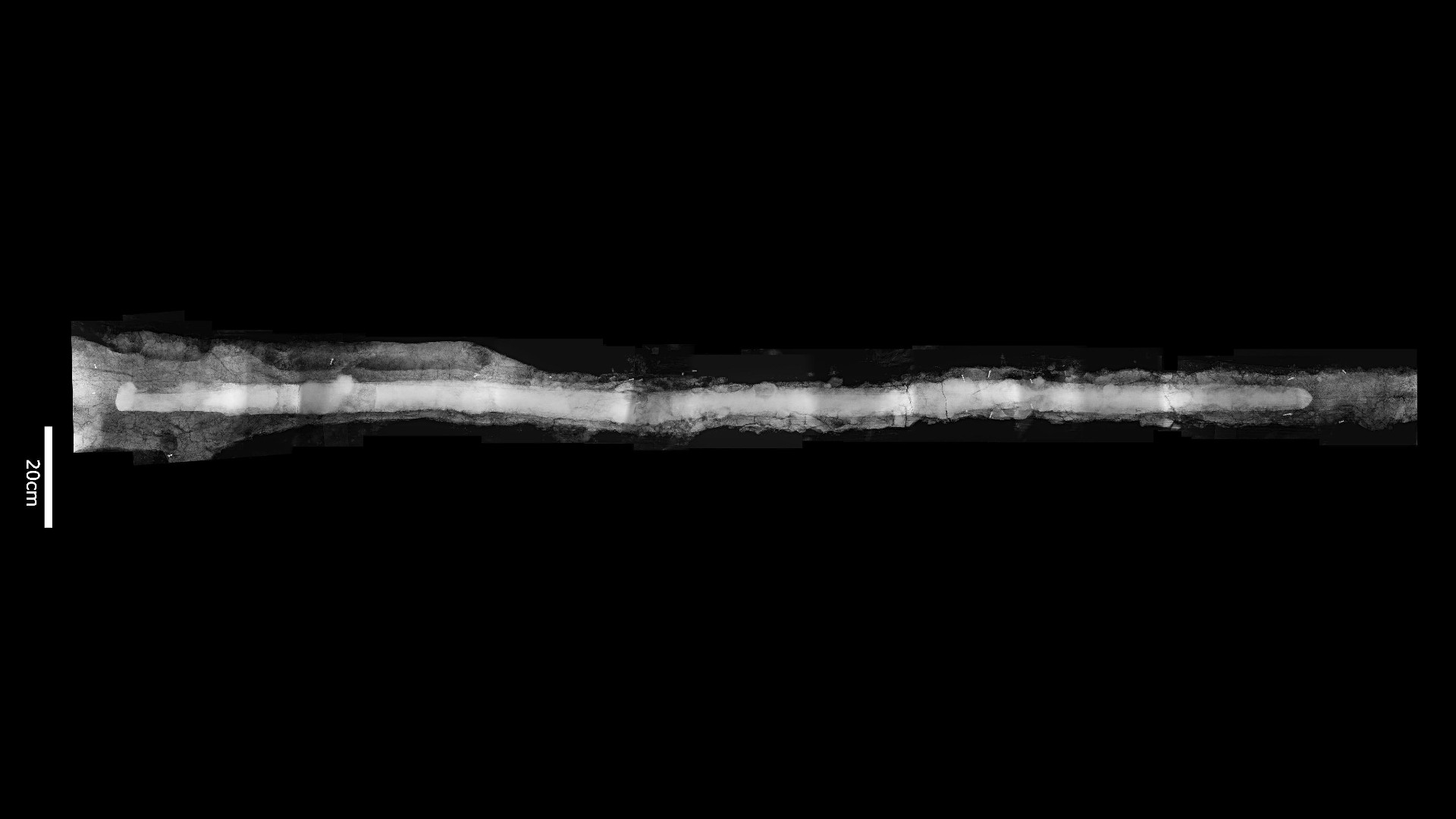

Archaeologists in Japan have unearthed a 7.5-foot-long (2.3 meters) iron sword during excavations of a 1,600-year-old burial mound near the city of Nara. The sword was too large to wield as a weapon, so its purpose was probably to protect the person it was buried with from evil spirits, experts say.

"I was surprised," Riku Murase, an archaeologist for the Nara City Archaeological Research Center who unearthed the sword in a tomb within the burial mound, told Live Science in an email. "It was so long that I doubted it was true."

Murase discovered the sword during excavations of the Tomio Maruyama burial mound in late November. The mound is located in a park just west of Nara, and dates from about the fourth century A.D.

The lengthy weapon is an example of a "dakō" – swords with a distinctive wavy or undulating blade, a bit like the kris knives of Indonesia.

Dakō swords have been found in other ancient Japanese tombs, but the size of this one is exceptional: "It is twice as big as any other sword found so far in Japan," Murase said.

Burial mound

The Nara region is peppered with thousands of burial mounds, which are known as "kofun" after the Kofun period of Japanese history when they were built, between A.D. 300 and 710.

Kofun are also found elsewhere in Japan, and it is estimated there may be as many as 160,000 throughout the country. The smallest are about 50 feet (15 m) across, but many are hundreds of feet across.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Nara's Tomio Maruyama kofun, where the sword was found, is one of the largest in Japan, with a diameter of more than 350 feet (100 m) and a height of up to 32 feet (10 m). The kofun may commemorate the burial of a person related to the imperial Yamato family, Murase said. However, excavations of the mound have unearthed only a large coffin, and not any human remains.

Archaeologists have found several important artifacts from the Kofun period in the Tomio Maruyama kofun, including iron farming tools, eating utensils and containers made from copper.

The latest excavations also unearthed a large bronze mirror, shaped like a shield, which is about 2 feet (60 centimeters) long and about a 1 foot (30 cm) wide; like the oversized sword, archaeologists think it was intended to protect the dead from evil spirits.

"(These discoveries) indicate that the technology of the Kofun period are beyond what had been imagined," Kosaku Okabayashi, the deputy director for Nara Prefecture's Archaeological Institute of Kashihara, told the Kyodo News Agency. "They are masterpieces in metalwork from that period."

Ancient sword

Archaeologist Stefan Maeder, an expert in Japanese swords and ancient sword-making, said the undulating or wavy dakō swords found in other Japanese burial mounds seemed to be mainly ceremonial. "I would not say they are common," he told Live Science. "They are prestigious objects of high society." But he notes that many practical fighting swords have also been found.

He noted that there was a tradition in Japan in later centuries of oversized swords being offered to deities or powerful spirits; many are still preserved in their treasure houses of Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples.

The distinctive undulating shape of dakō swords may represent a dragon or a snake, and may have been intended to increase their perceived magical power, although it did not increase their effectiveness as weapons, he said.

The swords in Japanese burial mounds might also represent a spiritual link between Japan, which at the time was considered the "center of the world", and the heavens — sometimes suggested in tomb artwork and on swords themselves by the distinctive pattern of the stars of the Big Dipper, or Great Bear (Ursa Major), a constellation that circles the celestial North Pole.

But Maeder is not sure if that is the case with the oversized dakō sword found at the Tomio Maruyama kofun: "It would be very interesting to see the orientation of the sword," he said.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus