Unusually Large 2-Billion-Year-Old Microbe Fossils Reveal Clues About Our Ancient World

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

BELLEVUE, Wash. — Not all fossils are remnants from ferocious dinos. Some of them are teeny-tiny blobs.

Scientists recently discovered some of these blobs in the form of 2.5-billion-year-old fossils of primitive bacteria. These ancient microbes are likely cyanobacteria, but they are unusually large and have weird shapes protruding from them, said Andrew Czaja, an associate professor at the University of Cincinnati, who presented his findings on Wednesday (June 26) at the Astrobiology Science Conference.

If these fossils really are cyanobacteria, they could be some of the primitive organisms, or their ancestors, that helped transform our atmosphere by pumping it with oxygen. But not everyone is convinced. [In Images: The Oldest Fossils on Earth]

The newly discovered fossils come from a period 100 million to 200 million years before the Great Oxidation Event — when our atmosphere went from having no oxygen to having a little bit.

"This is a very important time in Earth's history, both in terms of the evolution of the Earth but also the evolution of life," Czaja told Live Science.

Yet, "we don't actually have many instances of fossils from this time period." Czaja said. Czaja said he knew of only four cases in the literature of microfossils dating to between 2.5 billion and 2.7 billion years ago.

Czaja was exploring in South Africa when he happened upon a cool-looking rock, called a stromatolite, which is made up of layers of limestone and sediments left behind by cyanobacteria.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

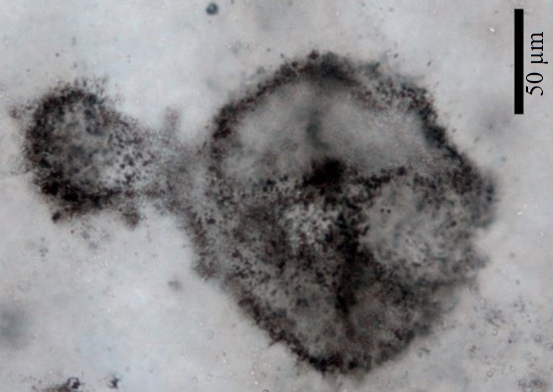

He brought it home to show during his classes, but it turned out the rock was chock-full of microfossils. Andrea Corpolongo, a doctoral student also at the University of Cincinnati, then began to analyze the rock under a microscope. The fossils turned out to be hollow spheres made of an organic compound called kerogen. Some of those spheres were oblong and some had weird protrusions coming off them.

The researchers don't know exactly what kind of microbes they're looking at, but because these fossils were found in the stromatolite, they may be ancient cyanobacteria. Yet some of them are bigger than any cyanobacteria we have today.

Nowadays, most cyanobacteria range from 5 to 10 microns, with the largest of these creatures measuring 60 microns, Czaja said. These ancient microbe fossils have a wide range of sizes, but most are above the average size of today's cyanobacteria and some are up to 100 microns across.

They also don't know why some of them have weird protrusions, which at first glance seem to be a type of "budding," orf asexual reproduction in which a part of an organism splits off to become a new organism. Nowadays, cyanobacteria don't bud and so "i'm not really claiming it's budding, but it does look like that," he said.

Emily Kraus, a doctoral student at the Colorado School of Mines, wasn't convinced.

"What he says are microfossils are very large," said Kraus, who wasn't involved with the new research. "They're larger than cells and cyanobacteria, which don't look like that, so I wasn't terribly convinced that that was a cell." The so-called fossils might even be fluids that got trapped in there and then slowly evaporated, she said.

But Corpolongo doesn't think that's likely. "Although their morphology does make them appear somewhat droplet-like, I cannot imagine a scenario during the formation of the stromatolite in which that could have occurred," she said.

It is possible, but unlikely, that the strange shapes are a pseudofossil, or something that looks like a fossil but isn't, she said. But the fact that they are made up of organic material and several of them were found preserved in stromatolites, which are known to be formed by microbes, "indicate that they are true fossils," she told Live Science.

Nora Noffke, a sedimentologist at the Old Dominion University in Virginia who was not a part of the study, thinks it's possible that those fossils are cyanobacteria.

"I'm intrigued by those microfossils," Noffke told Live Science. They look a bit "as if they would sprout I've never seen anything like that," Noffke added.

Still, there are "many ways to interpret" their findings, she said..

Czaja, for his part, is hoping to go back to South Africa to see if he can find similar microfossils in nearby areas. "It would tell us more about the microbial communities that existed at this time," he said.

These findings have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

- Photo Timeline: How the Earth Formed

- These Bizarre Sea Monsters Once Ruled the Ocean

- 7 Theories on the Origin of Life

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus