In Photos: Stunning Treasures from the Burial of an Anglo-Saxon Prince

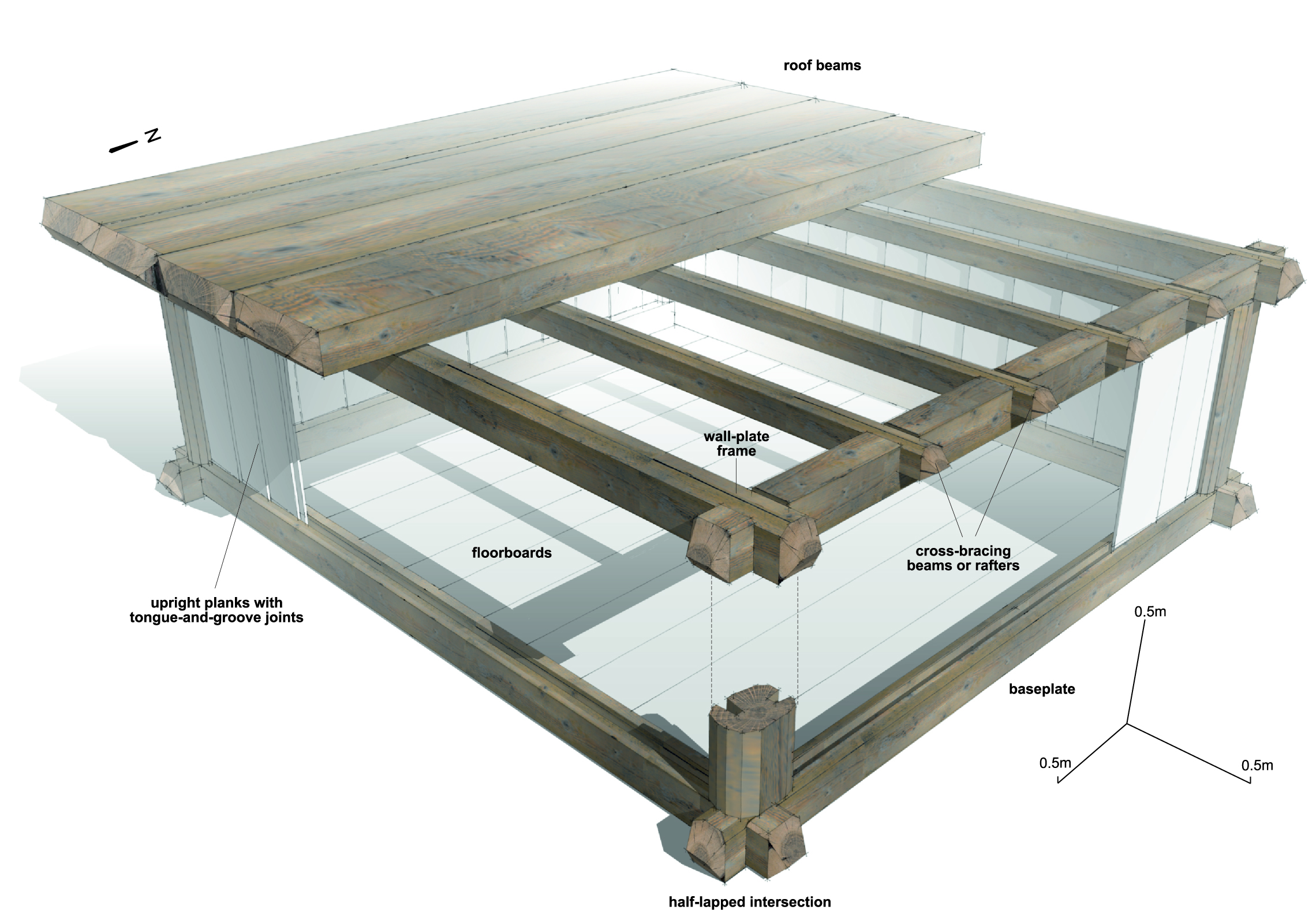

Tomb Construction

A reconstruction of the timber-built burial chamber near Prittlewell. Archaeologists estimate that it would have taken 13 oak trees and 113 person-days of work to build the tomb. A group of 20 to 25 people could have done the job in five days, according to the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA), though it would have taken another 18 to cover the tomb and build a burial mound over it.

Testing the Metal

Researchers use a portable X-ray fluorescence machine to analyze the metal alloys that make up a drinking bottle found in the Prittlewell tomb. This handheld device beams X-rays at an object and measures the secondary X-rays emitted in response. The patterns of these reflected X-rays can reveal what elements make up the object; in this case, the metal was gilded copper.

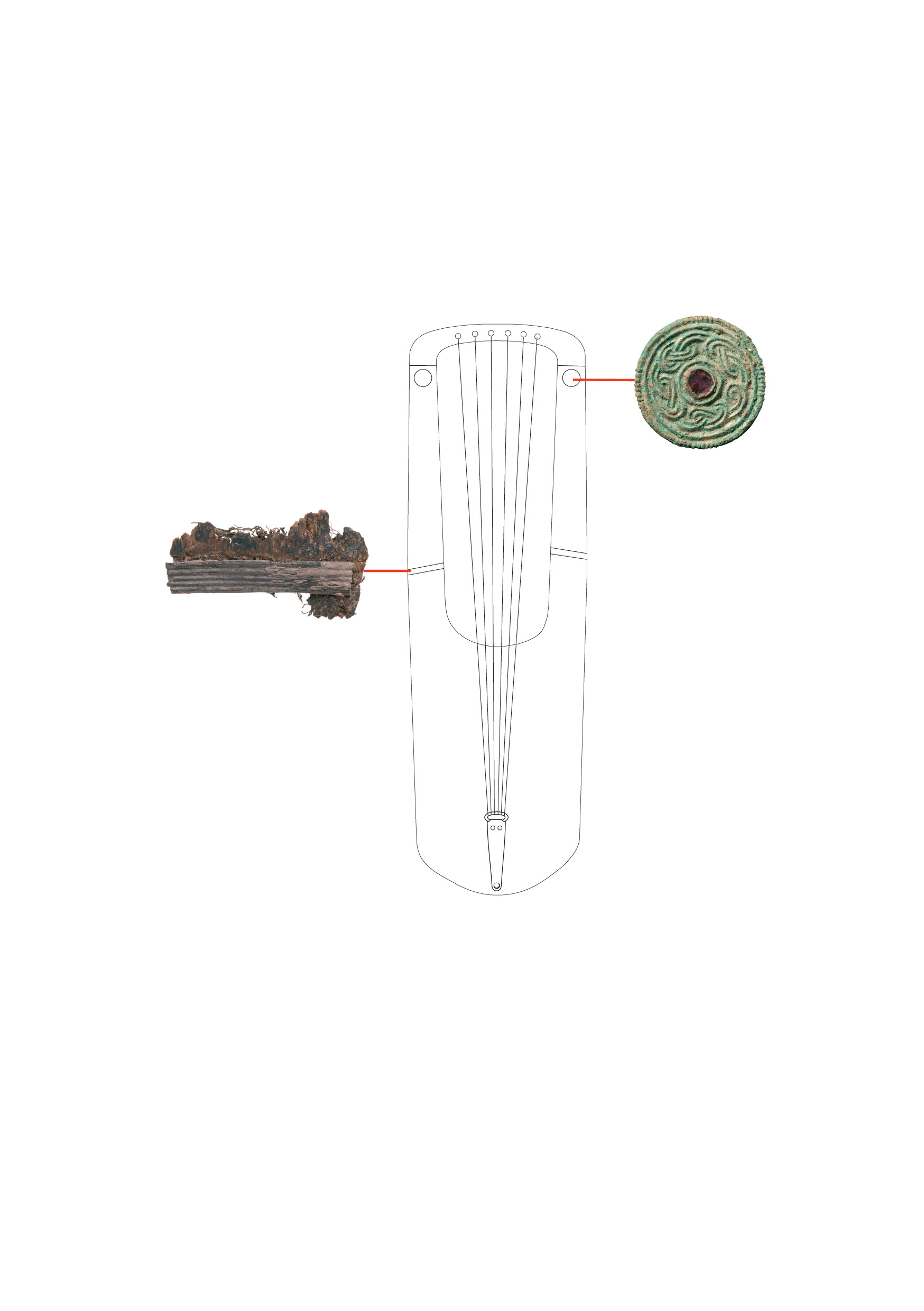

Reconstructed Lyre

Based on a few metal fittings and a chemical analysis of the soil stains left by rotting wood, archaeologists have reconstructed a lyre buried with the Anglo-Saxon aristocrat. The instrument was made of maple, with ash tuning pegs. The item was apparently much beloved: The body of the lyre had split at some point and had been repaired with metal fittings, some of which sported garnets from the Indian subcontinent.

Copper Flagon

Like the garnets on the lyre, this copper-alloy flagon came from a faraway land. Archaeologists found that this flagon — which was decorated with medallions bearing the image of fourth-century St. Sergius — was made in the Middle East, probably Syria. Such vessels were often brought back to Northern Europe by Christian pilgrims.

Fragile Remains

While many of the organic materials in the chamber had rotted away, some pieces of wood that were in contact with minerals managed to stay intact. Here, an expert in mineral-preserved wood examines some of these fragments in the lab.

Careful Excavation

An archaeologist carefully excavates the Prittlewell burial chamber. The chamber was discovered in 2003; it has taken researchers 16 years to carefully remove, clean and analyze the artifacts. Many will now be on permanent display at the Southend Central Museum in Southend-on-Sea, England.

Beautiful Bowl

Displaying a blue-green patina of age, this copper-alloy bowl was discovered in the original place in which it was interred, hanging on the burial chamber wall of an Anglo-Saxon prince. The dish was made in Britain, according to archaeologists.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Drinking Horn

The metal rim of a drinking horn found near the coffin of the Anglo-Saxon prince. Dating this object helped to reveal the age of the tomb, which is about 1,400 years old. Along with coins found in the resting place, this object suggests that the burial occurred between A.D. 580 and 605. Because drinking horns like these were high-status objects, the artifact helped to establish that the tomb's occupant was an aristocrat.

Drinks After Death

A series of drinking vessels shown as they were originally discovered in the Prittlewell burial chamber. The tomb's occupant went to the afterlife with a hunk of beef and – possibly – buckets of ale, as well as a large cooking cauldron, cups, flagons and other vessels.

Gold Necks

Decorated gilt necks of drinking vessels emerge from the soil at the Prittlewell site. The goods buried in the chamber indicate that the person interred there was a powerful and high-status individual.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.