Photos: Cretaceous 'Night Mouse' Was a Wee Mammal

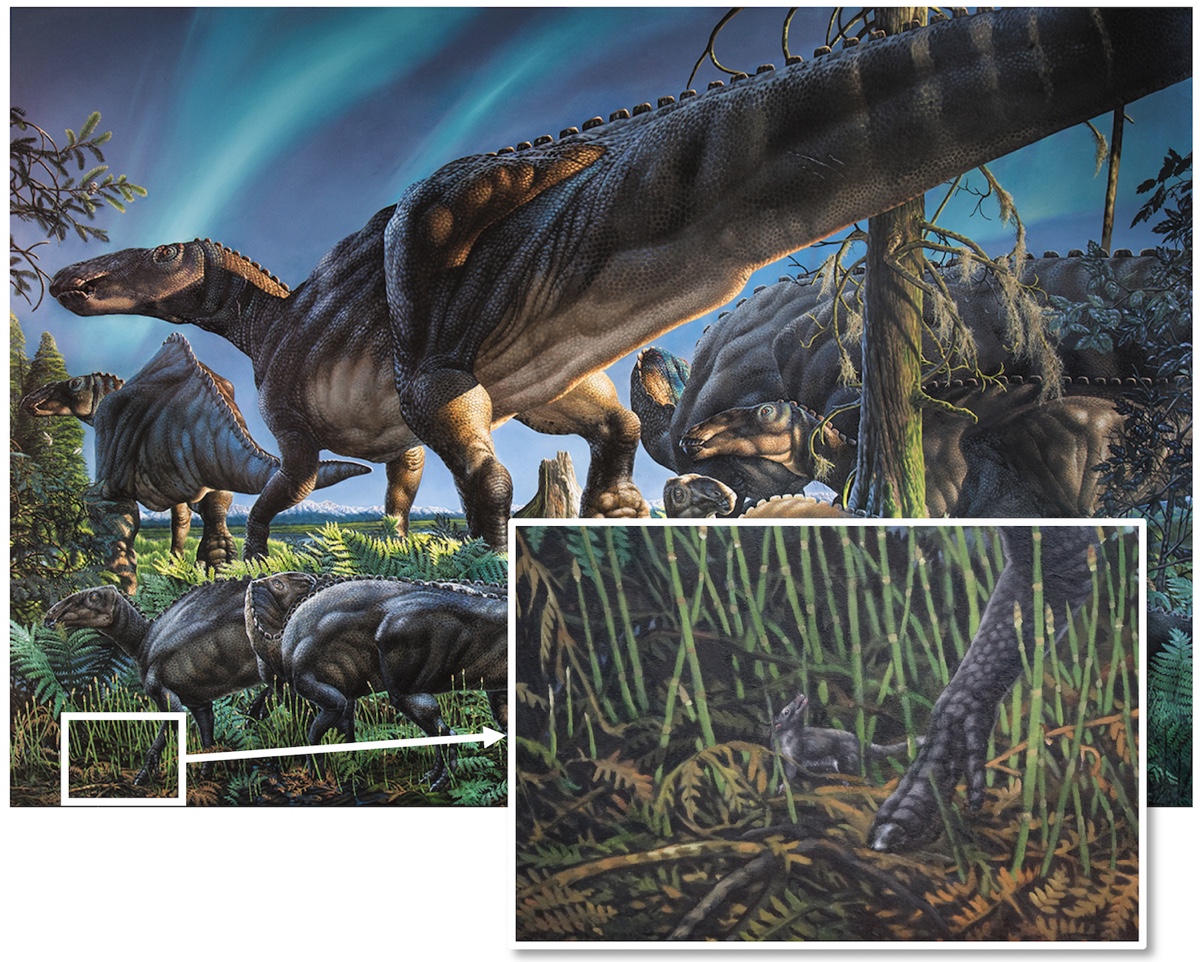

Meet the 'Night Mouse'

Paleontologists have unearthed a new 69 million-year-old mammal species in the North Slope of Alaska. They call the Cretaceous creature Unnuakomys hutchisoni, a combination of local indigenous language and Greek that roughly translates to "night mouse." This mural shows an artist's conception of the mouse-sized animal scampering at the feet of the dinosaurs.

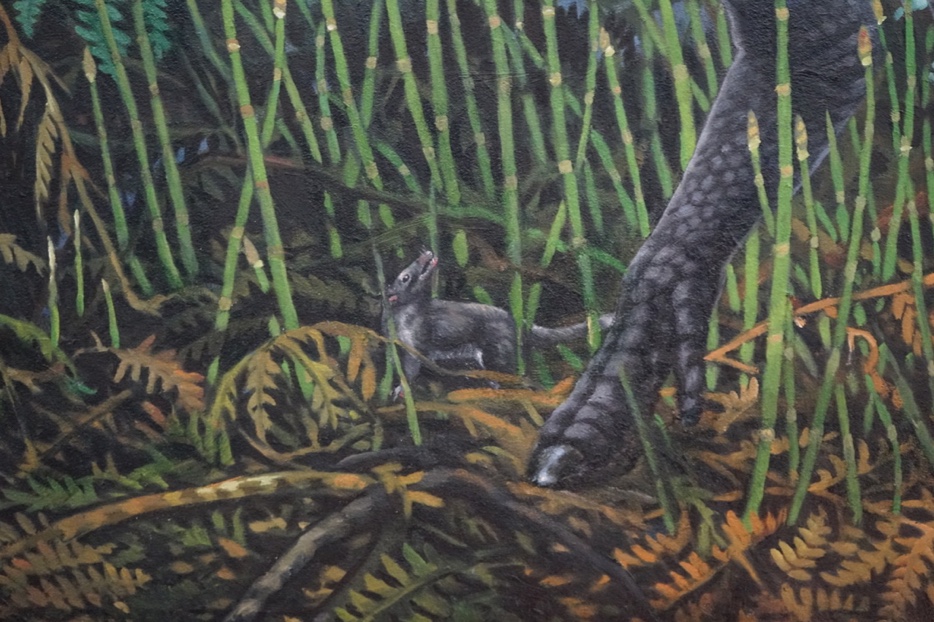

Cretaceous hide-and-seek

Imagine Unnuakomys hutchisoni in this mural depicting the Arctic landscape of the late Cretaceous. Today's excavation site lies at 70 degrees north latitude, but the landmass was at between 80 and 85 degrees north 69 million years ago. The climate was warmer than today, and conifer forests dominated the landscape.

Now you see it

Did you find the night mouse? An inset panel shows the tiny animal amidst duck-billed dinosaurs (Ugrunaaluk kuukpikensis), whose fossils have also been found in Alaska's North Slope. The excavation site lies along the steep banks of the Colville River, where paleontologists wearing hardhats attempt to remove fossils before they erode in mini-avalanches into the water below.

Sifting the sediment

Paleontologists from the University of Alaska Fairbanks pose with buckets full of sediment from the banks of the Colville River. The sediment buckets are headed back to the paleontology lab, where scientists and research assistants painstakingly sift through them under microscopes, looking for teeth just hundredths of an inch (millimeters) in length.

Camping on the Colville

Tents pitched on a sandbar along the Colville River in Alaska, above the Arctic Circle. At night, researchers camping in the tents can hear the river's banks periodically crumble, splashing dirt and rock into the water below, Eberle told Live Science. The weather is cool, even in the summer, and frequently damp.

Snowy fieldwork

Researchers perch on a riverbank above the Colville River in Alaska, excavating for dinosaur bones and Cretaceous mammals in the Prince Creek Formation as snowflakes fall. During the summer, the area gets 24 hours of sunlight. In winter, 24-hour darkness lasts for four straight months.

On the North Slope

Researchers carefully collect sediment from the banks of the Colville River, picking through a layer just a few inches thick that represents a time period around 69 million years ago. Scientists have found about 70 teeth and a jawbone from the "night mouse" in this layer. They've also discovered scattered teeth from other Cretaceous mammals, though those have yet to be fully analyzed.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

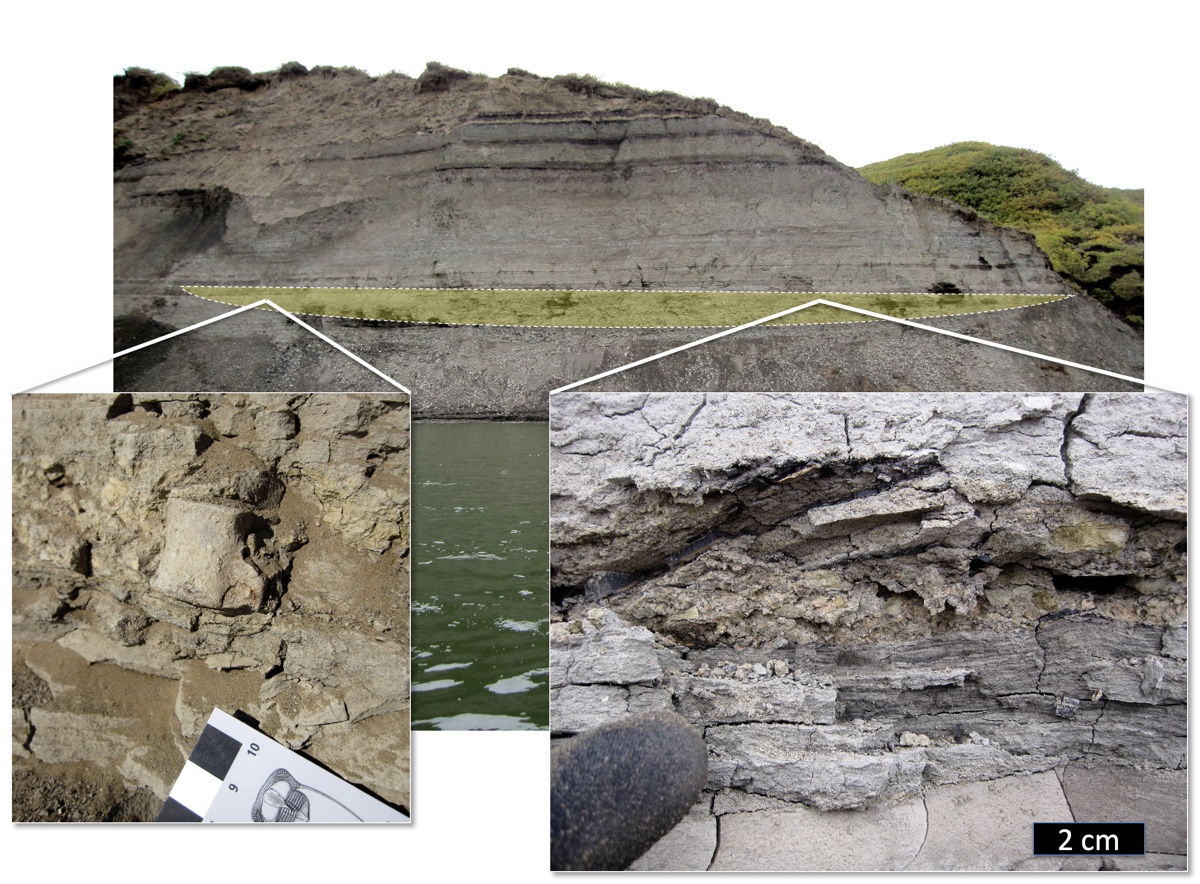

A look at the layers

Layers of sediment and rock above the Colville River where the research team found the teeth of a tiny new Cretaceous mammal. The animal is related to today's marsupials and may have looked like a teensy version of today's opossums. Scientists have been excavating in this area for decades and have also discovered fossils of tyrannosaur relatives and duck-billed dinosaurs.

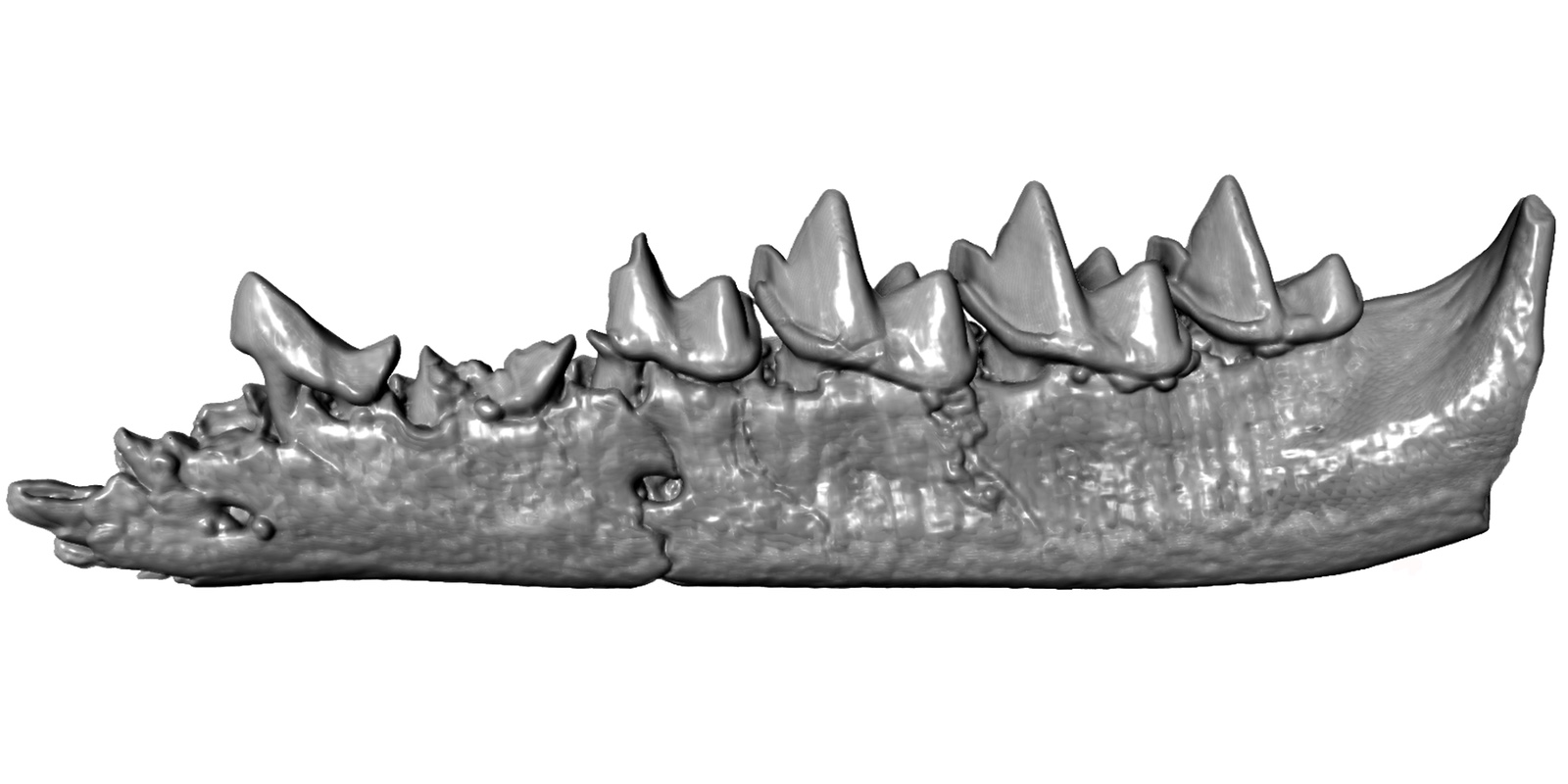

A look at the layers

A three-dimensional computer rendering of the jaw of Unnuakomys hutchisoni. The jaw is less than a centimeter (0.39 inches) long and the longest teeth are only about 0.06 inches (1.5 millimeters) in length. Based upon the size of the teeth, scientists believe that U. hutchisoni weighed only about an ounce, the size of a small shrew or mouse.

First pass

Using sifters, University of Alaska, Fairbanks researchers do a first pass on buckets of sediment in the field. The screened materials will be taken to the lab for more detailed sorting. Eberle's team at the University of Colorado, Boulder, is still working through five buckets of sediment from last season's dig. They hope to find more new mammal species.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus