Kite-Blown Sled Climbs Antarctic Ice Dome, One of the Coldest Places on Earth

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

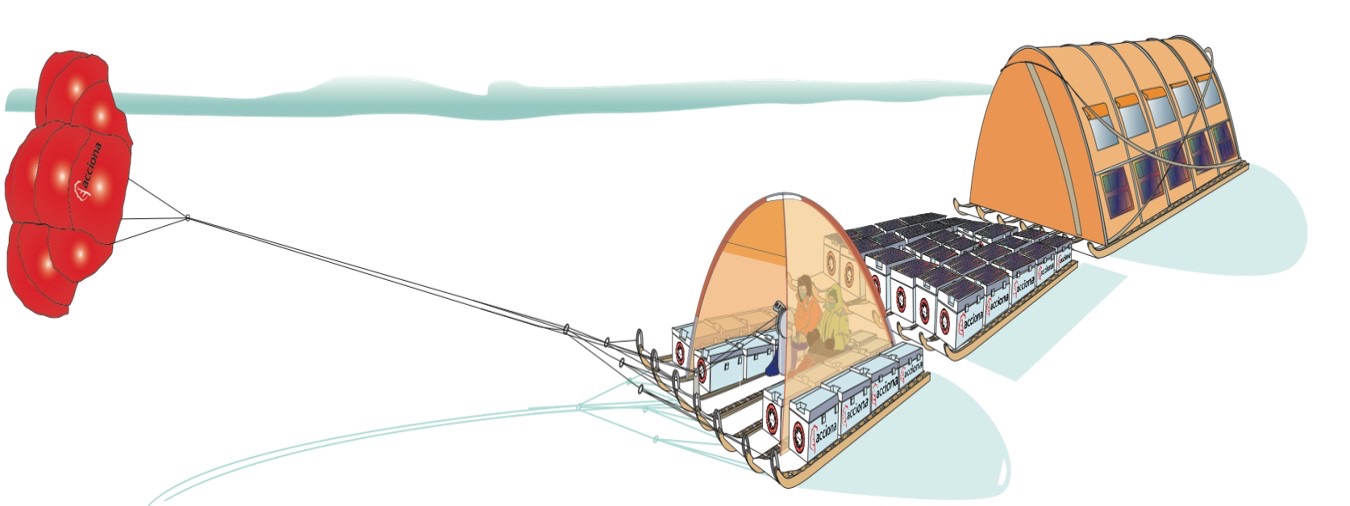

For the first time, an expedition climbed one of the coldest places on Earth — Fuji Dome in the interior of East Antarctica — using a windblown vehicle.

During the 52-day voyage, undertaken by Spain's Asociación Polar Trineo de Viento, a four-person team used the "WindSled" to ascend the icy 12,500-foot-tall (3,810 meters) dome.

Tents, cargo, scientific experiments and solar panels were mounted on the truck-size, modular sled and pulled by a 1,600-square-foot (150 square meters) kite. [Icy Images: Antarctica Will Amaze You in Incredible Aerial Views]

"It has been difficult, but we consider this crossing a great scientific, technical and geographical success," WindSled inventor Ramón Larramendi said in a statement today (Feb. 5). "We have proved that it is possible to travel thousands of kilometers, with two tons of cargo, without polluting, and performing cutting-edge science, in a complex and inaccessible territory such as Antarctica."

The team left from the Russian Novolazarevskaya Base in Antarctica on Dec. 12 and traveled 1,577 miles (2,538 kilometers) during their round trip, enduring temperatures as low as minus 43.6 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 42 degrees Celsius).

The highest elevation the expedition recorded was 12,362 feet (3,768 meters), just short of Fuji Dome's highest point, which is apparently difficult to identify as the landscape is more like a plain than a peak.

The WindSled didn't make it through the journey entirely intact. The team reported that the kite suffered a rip after it was under pressure from soft snow and low winds during part of the voyage.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In addition to demonstrating possible uses for the vehicle, the team also conducted several scientific experiments.

The 11 scientific projects on board the WindSled included a special drill for sampling snow and ice for researchers at the University of Maine to study the history of climate change. The team also tested the sensors for the Mars Environmental Dynamics Analyzer (MEDA), an instrument that will be on NASA's Mars 2020 Rover to measure wind, temperature, dust and other weather factors.

The expedition was also carrying the Spanish Astrobiology Center's Signs of Life Detector, an instrument designed to detect signs of cold-adapted bacteria and viruses that could offer a glimpse at how microbial life might survived on other planets.

The European Space Agency (ESA) contracted the expedition to test the performance of Europe's new, nearly complete global navigation satellite system, Galileo, which is a rival to systems like the United States' GPS, in an experiment dubbed GESTA.

"We are very pleased with this pilot scientific experience, having been able to collect Galileo measurements all over the expedition trip as planned," Javier Ventura-Traveset, head of ESA's Galileo Navigation Science Office, said in a statement from ESA. "The expedition reached latitudes near 80 degrees south, to our knowledge the most southerly latitude measurements ever-performed in-situ with Galileo in its current near-complete constellation status."

The GESTA measurements should also give researchers insights about how geomagnetic storms caused by solar activity can degrade satellite navigation performance.

"At this moment in the 11-year solar cycle, with the sun close to minimum activity, full-scale solar storms are not frequent, but the ongoing communication between the WindSled team and the Galileo Navigation Support Office allowed us to coordinate measurement times during the three minor geomagnetic storms the expedition experienced during the trip," said Manuel Castillo, system engineer at the Galileo Navigation Science Office.

- Antarctica: The Ice-Covered Bottom of the World (Photos)

- Antarctica Photos: Meltwater Lake Hidden Beneath the Ice

- In Photos: Research Vessel Headed to 'Hidden' Antarctic Ecosystem

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus