Tiny-Headed, Ancient ‘Platypus’ with Stegosaurus Back Plates Unearthed

The so-called prehistoric platypus certainly didn't look intelligent. Its little head was strangely out of proportion with its large body and its tiny eyes probably couldn't see much. But despite this, it still found a way to hunt unsuspecting prey.

Just like the modern platypus, this 250-million-year-old, Triassic-age marine reptile likely used its cartilaginous bill to discover and seize its next meal, a new study finds.

"This animal had unusually small eyes for the body, only rivaled by some living animals that rely on senses other than vision and feed in the dusk or darkness — for example some shrews, badgers and the duck-billed platypus," said study lead researcher Ryosuke Motani, a paleobiologist at the University of California, Davis. "So, it most likely used tactile senses [with its] platypus-like bill to detect prey in the dusk or darkness." [12 Extremely Weird Animal Feet]

He added that "at this point, the species represents the oldest record of such small-eyed vertebrates with four limbs."

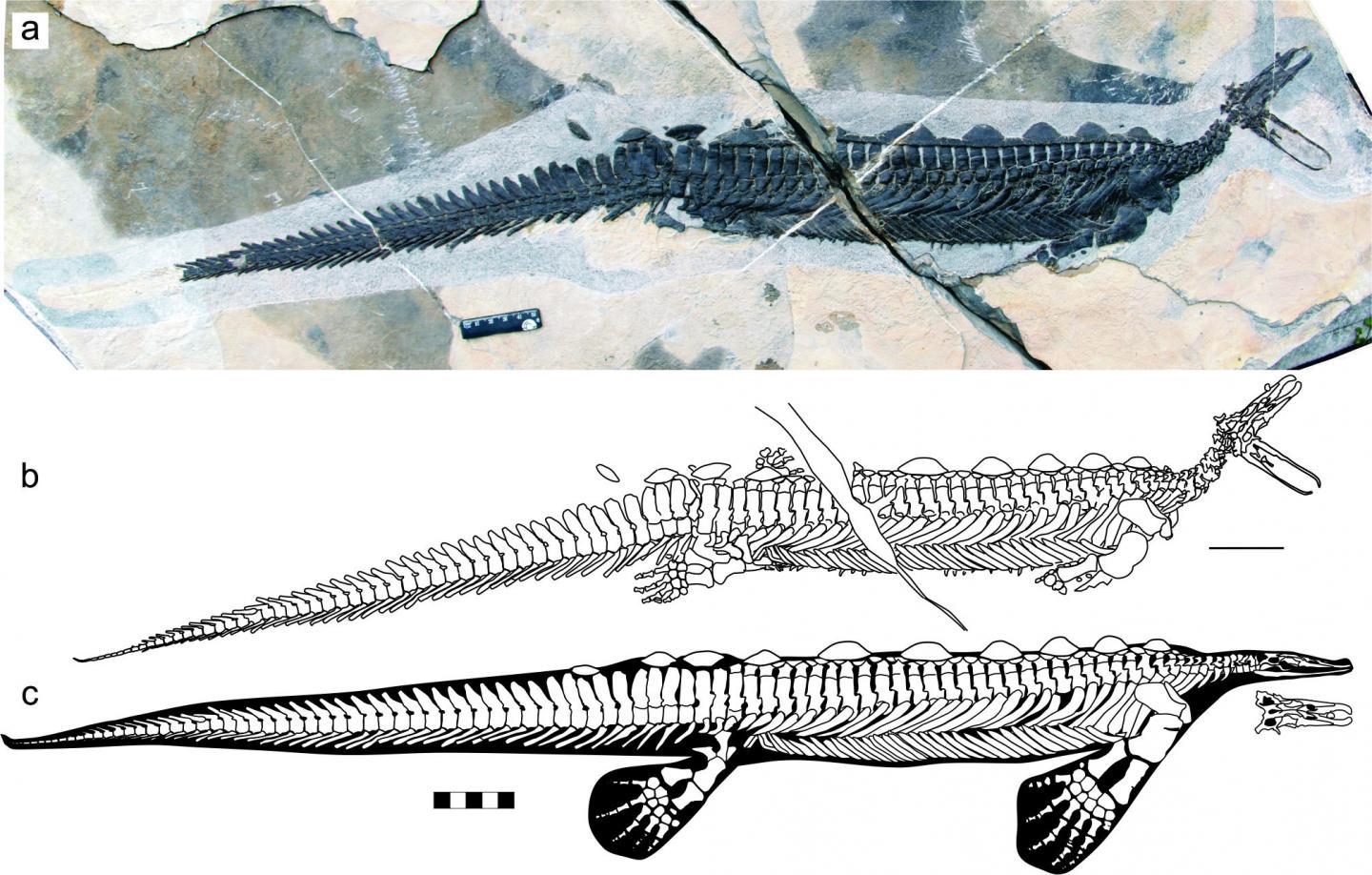

Previously, scientists had only partial, headless fossils of the creature, known scientifically as Eretmorhipis carrolldongi. But about a decade ago, study co-researcher Cheng Long, of the Wuhan Center of China Geological Survey, and his team were invited by the government of Yuan'an County, Hubei province, to excavate the lower Triassic Jialingjiang Formation. It was there that they unearthed a spectacular E. carrolldongi specimen, including its tiny head, Long said.

The local government was so impressed, it "built a geological museum for [its] display," Long told Live Science. And "recently, the area became a national geological park."

The 2.3-foot-long (70 centimeters) E. carrolldongi had a lengthy, rigid body, four flippers and triangular bony blades sticking out of its back, "somewhat like in the dinosaur Stegosaurus — [it's] very bizarre looking," Motani told Live Science. The critter likely ate soft invertebrates, such as shrimp and possibly worms.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers quickly identified what the platypus-like creature couldn't do well: It likely had dismal hearing because sound localization in the water is difficult for small-headed animals. And, it probably couldn't taste much with tongue-flicking because it lacked a structure in its palate that helps convey chemical information from the tongue to other sensory organs.

"This leaves the tactile sense as the most likely candidate among the traditional five senses," the researchers wrote in the study.

E. carrolldongi was distantly related to ichthyosaurs, dolphin-like reptiles that swam through the seas during the dinosaur age. Previously, many researchers thought that marine animal diversification slowed for about 8 million years after the end-Permian mass extinction 252 million years ago. But now, the discovery and analysis of E. carrolldongi shows that marine reptiles had remarkable diversity shortly after that mass extinction, Motani said.

"Slightly after the end-Permian mass extinction, there were a lot of open opportunities as life recolonized the Earth's surface," Motani said. "These bizarre forms grabbed the open niches and diversified, but were soon wiped out, probably by natural selection. The animal in question is one of them — it must have been a slow swimmer and an inefficient feeder, but that was sufficient for the time being."

The study was published online today (Jan. 24) in the journal Scientific Reports.

- Image Gallery: Ancient Monsters of the Sea

- In Images: Graveyard of Ichthyosaur Fossils in Chile

- Images: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.